About a dozen brave individuals gathered at the Zenger apiary colonies Sunday April 15th, during a steady Oregon liquid “sunshine” rain for dead colony forensics with Dewey. Photo right by Mandy Shaw.

About a dozen brave individuals gathered at the Zenger apiary colonies Sunday April 15th, during a steady Oregon liquid “sunshine” rain for dead colony forensics with Dewey. Photo right by Mandy Shaw.

Temperature was low 50’s, with only a couple foraging bees venturing forth from 4 of 8 colonies. We hefted boxes and did autopsy on two dead-outs.

Bees die overwinter for a number of reasons. By doing a dead colony autopsy we seek to determine what might have been the likely reason for non-survivorship. Understanding the why might help us avoid a repeat this next winter.

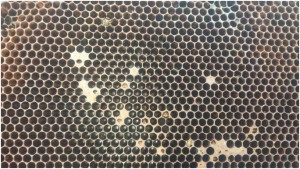

The first dead-out we looked at (photo above) proved to be a tough diagnosis.

The first dead-out we looked at (photo above) proved to be a tough diagnosis.

The colony was a mid-May nuc donation from Beetanical apiaries of Lane Co. Hive had a standard and a shallow. The shallow frames were quite full (>3/4ths of cells) with capped honey. The shallow was lifted off and placed on upside-down cover. There were dead brood remains on three frames of the lower standard box plus a small (<2000) number of dead adult bees on the screen bottom board and outside the entrance. Two adjacent frames had widely scattered capped brood cells extending in an oval covering over 1/3 of the middle of the frames; there was a fist-sized patch of compact capped brood but it was not contiguous with the scattered brood of the other two frames. There was no evidence of a dead cluster but a considerable number of cells of stored pollen on 5 frames. Ample mold was evident in pollen cells and as a powdery grayish mold on surface of cells. Colony was sampled for mites with a sugar roll in September and had only 2 mites (<1%). It was NOT treated for mites as it was a non-treatment control. Colony was alive in a mid-October inspection.

Photo of the three frames with brood shows the frame with a patch of compact brood (held in my right hand) and two frames with very scattered brood (one in my left hand and the third on top of adjacent hive; this frame is shown isolated in photo right). Full super on ground. Photos by Deb Caron.

Photo of the three frames with brood shows the frame with a patch of compact brood (held in my right hand) and two frames with very scattered brood (one in my left hand and the third on top of adjacent hive; this frame is shown isolated in photo right). Full super on ground. Photos by Deb Caron.

So what can we diagnose? Lots of honey and pollen stores so we can likely rules out starvation. Small number of dead bee bodies suggests a small colony but if we would believe death from a too-small population of adults, there should have been evidence of a cluster with bees within cells and dead bee remains on the frame(s). There wasn’t.

Thus our best guess is a colony that had a BEE PMS condition. The scattered brood remains on both sides of the two frames suggests this –a spotty (snot) brood situation MIGHT have been diagnosed in the October examination, but this requires a close examination of the brood; we might have noticed evidence to too few adult bees to cover the brood – both are subtle clues. The fist-sized brood area, one frame over from the other two frames with scattered brood, might have been bees trying to escape the high mite numbers and their unhealthy brood of the 2 frames with scattered cells. Adult bees were likely dying prematurely and abandoning their (unhealthy) hive, thus the reason we saw only a smallish number of adult dead bees. The colony likely failed to rear sufficient fat, fall bees. The colony probably died within a month after the last October inspection, probably from a virus epidemic related to the mite infestation. NOTE: The September mite sample is misleading/confusing (we would expect it to have been higher); if an additional sample was taken it would perhaps have been higher?

The second dead-out was a more standard necropsy. Hive was a spring split,that struggled all season. It had 2 shallows. Colony had a 19 mite count (6%+) in September and was treated with 2 formic pads between the two boxes. It was alive in March (this spring) but noted as small. It was fed dry sugar on paper (some still remaining) and provided with a frame of sugar candy.

The second dead-out was a more standard necropsy. Hive was a spring split,that struggled all season. It had 2 shallows. Colony had a 19 mite count (6%+) in September and was treated with 2 formic pads between the two boxes. It was alive in March (this spring) but noted as small. It was fed dry sugar on paper (some still remaining) and provided with a frame of sugar candy.

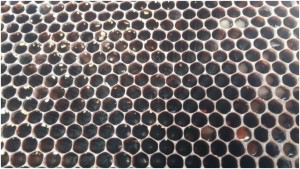

Opening the top and removing moisture trap, (all Zenger hives had moisture quilt traps at top) showed a dead cluster of adult bees on 3 frames in top box at top of the box extending down about ½ way on the 3 frames (see photos; in photo right, hive tool is showing the remaining dry sugar on paper – quilt trap with wood shaving lower right). The adult bees were black and showed excessive moisture; there were many maggots (scavenger fly) feeding on the dead bees. There was capped brood in compact pattern within the cluster. Dead adult population was small (perhaps 8-10,000 bees). There was NO capped honey in any of the frames of either box. Lower box was empty. There were some dead bees on solid bottom board. There was little mold.

So what was diagnosis? The dead cluster is characteristic of a colony that overwintered the tough months (Dec-Feb) and moisture of adult bees, maggots and little mold suggests recent death. The compact brood shows the colony was starting to expand in the spring (flight was noted in March). Although dry sugar (as candy and crystal sugar) was given as emergency feed (hefting would have revealed lack of enough stores), it turned out to not be enough — colony likely starved. Bee cluster too small to generate enough heat to make slurry out of dry sugar or candy so bees couldn’t use it. Photo below shows one of three frames. We see “bee butts” under the dead cluster and compact capped brood. Photo by Deb Caron.

All frames, except one with high number of drone cells, could be reused for anew colony installation (package, swarm, split). Brush off dead cluster and from bottom board. If inclined wash mold with bleach or vinegar solution.

All frames, except one with high number of drone cells, could be reused for anew colony installation (package, swarm, split). Brush off dead cluster and from bottom board. If inclined wash mold with bleach or vinegar solution.