-

Recent Posts @ the Buzz

- The 2023-2024 Bee Survey is now LIVE!

- The Reluctant Spring of 2023

- 2022-2023 Bee Survey is OPEN!

- 2021-2022 Survey Announcement

- Surviving Wildfires & Ice storms – 2020-2021 Survey Announcement

- Q & A – Barely Surviving Spring

- Q & A – Treatment Free Studies

- Q&A – Agricultural sprays & our bees

- 2019-20 Honey Bee Survey is on!

- Q&A – cold/snowy loss

Tags

AFB agricultural crops bee disappearance Brood colony loss confusion costly hobby dead bees dead out drone education Feeding fondant future survey hive loss Honey honey flow honey stores mentors mite mite control mites moisture multiple choice nucs overwinter oxalic acid packages PMS pollen pollination queen sanitation season split spraying survey confusion Survey glitch swarm top bar treatments Varroa Varroa mite control Warre yellow jacketsArchives

- March 2024 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- March 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (1)

- March 2019 (22)

- February 2019 (1)

- July 2018 (2)

- June 2018 (1)

- May 2018 (2)

- February 2018 (1)

- May 2016 (58)

- April 2016 (1)

- February 2016 (1)

- November 2015 (1)

- September 2015 (3)

- August 2015 (1)

- July 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (6)

- April 2015 (29)

Categories

- 2015 (5)

- 2015 Survey (38)

- 2016 Survey (55)

- Carons articles (15)

- Dr (4)

- Q & A (101)

- Results (1)

- Uncategorized (11)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

The Reluctant Spring of 2023

Keeping bees can be an adventure. This years “reluctant” spring has been a challenge. Usually by mid-April we have to split strong colonies or risk colony swarming. This year there were no reports of swarms by mid-April and beekeepers have reported only a few colonies that might be split. In truth early splits this year might mean poor mating of the virgin queens that the queenless split would need to prosper into summer without intervention. On the bright side our early PNWHoneyBee Survey returns are showing lower overwintering losses! Do keep in mind however that with our “reluctant” spring we risk having colonies run out of honey stores. As was the case last year, many beekeepers report adding more sugar candy or fondant candy cakes to their colonies for the last beekeeping season. Reminder – the PNW and BIP annual colony surveys are open until end of month. If you haven’t completed a survey please do so before May 1st.

Posted in Uncategorized

2022-2023 Bee Survey is OPEN!

National and regional loss/management surveys demonstrate the annual loss of bees overwinter fluctuates from one season to the next. It is not the coldest temperatures but fluctuating weather that is hard on bees. By January many colonies have brood, which winter pollen foraging promotes. In January and February colony size and amount of honey stores are most critical to overwintering success Effectiveness of previous season varroa mite control is also a critical factor.

It is still too early to be able to determine how colonies have fared during this winter, although early reports seem promising so far. Increasingly, winter survival models, using the extensive multiple years of loss data, are being utilized to seek to correlate losses with colony managements and environmental factors.

An earlier study from Penn State found overwintering success influenced by higher colony weight and size of the population colonies reached prior to winter. Origin of stock was not important, at least for central Pennsylvania. Higher temperature and precipitation during the warmest seasonal quarter was correlated with improved wintering success. Recently a detailed look at the data from the Bee Informed National Survey linked increased winter colony loss rates with winter weather. Specifically, November mean maximum temperatures and mean February precipitation predict success.

In Oregon and Washington annual colony loss is assessed with the https://pnwhoneybeesurvey.com For Oregon backyarders, the overall trend has been essentially flat over the past 13 years at just under 40% annual colony loss; for commercially managed colonies losses are one-half that level, at just above 20%.

The 2023 survey of the 22-23 winter and 2022 management season will be open for your participation mid-March through April. After you open your colonies and assess your winter success please take the time to enter your data in the survey. It should take less than 5 minutes. Reports by club are posted beginning within a month following survey close April 30th . Can we count on you entering your data and “beeing” among those counted? THANKS.

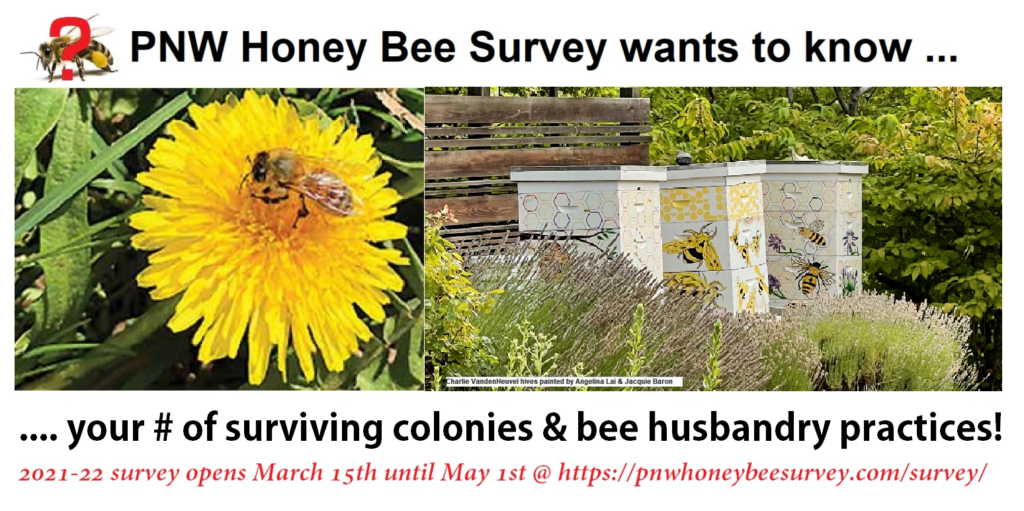

2021-2022 Survey Announcement

With improving spring weather check colony food stores by hefting at the back of the colony. If you feel the hive is short in required food you could consider feeding a homemade sugar brick until it warms up enough for syrup. Make a sugar brick by mixing a small amount of water to make a thick slurry of cane/beet sugar and letting it stand overnight to solidify. An alternative would be to feed drivert (confectioners) sugar. Do not use brown sugar or any sugar that contains starch.

Peek quickly under the lid & below covers for water staining or sign of excess moisture in the hive. If seen, consider using some form of absorption filler material, aka quilt box, for the remainder of damp months or plan for this addition to next year’s wintering set up. Colonies need to be insulated on the top so moisture does not accumulate under the cover and rain back down on the bees.

Clean bottom boards to clear the path for new bees and save them this task (& honey store energy). This could be something as simple as brushing clear with a down feather for now until the temperatures are above 60 degrees and it’s safe to physically open the hive long enough to clean the bottom board.

The 13th annual Pacific Northwest Honey Bee Loss Survey will open up EARLY this year www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com/survey You can start entering your overwintering successes/losses and management on March 15th . The survey will be available until May 1st. Please consider downloading and filling out the note sheet to aid in quick survey entry. Many have found that this simple resource has been key to have on hand in the bee yard throughout the year not only to track items but to remind of alternative bee husbandry options.

We hope to see great health in our PNW honeybees and fellow beekeepers this spring!

Posted in Uncategorized

Surviving Wildfires & Ice storms – 2020-2021 Survey Announcement

After our mild January the colder February is better for our bee colony overwintering in order to slow colony expansion.

Once the weather warms check on food stores by hefting at the back. It is too early to feed syrup as we do not want to stimulate or add to moisture stress.

If you feel the hive is short in required food you could consider feeding a homemade sugar brick until it warms up enough for syrup. Make a sugar brick by mixing a small amount of water to make a thick slurry of cane/beet sugar and letting it stand overnight to solidify. An alternative would be to feed drivert (confectioners) sugar but do not use brown sugar or any sugar that contains starch.

Peek quickly under the lid & below covers for water staining or sign of excess moisture in the hive. If seen, consider using some form of absorption filler material aka quilt box for the remainder of damp months or plan for this addition to next year’s wintering set up.

Clean bottom boards to clear the path for new bees and save them some labor (& honey store energy). This could be something as simple as brushing clear with a down feather for now until the temperatures are above 60 degrees and it’s safe to physically open the hive long enough to “change the underwear”.

The 12th annual Pacific Northwest Honey Bee Loss Survey will open up EARLY this year on March 15th and be available until May 1st. Please consider downloading and filling out the note sheet to aid in quick survey entry. Many have found that this simple resource has been key to have on hand in the bee yard throughout the year not only to track items but to remind of alternative bee husbandry options.

Lastly, if you would like an email reminder when the survey opens please visit https://pnwhoneybeesurvey.com/resources/reminder/ today.

We hope to see great health in our PNW honeybees and fellow beekeepers this spring!

2019-20 Honey Bee Survey is on!

The PNW loss survey is now available and will be open through April at https://pnwhoneybeesurvey.com/survey/. I trust your bees got through the Ides of March cold spell. If you entered data and something changes you can re-enter using same email and make changes – we CAN still lose colonies. Sugar is tough to find; if bees are able to get out there is a good bloom available but don’t neglect colonies that need supplemental feeding. Thanks for remaining the vital part of this research tool – Dewey

Posted in Uncategorized

Q&A – high varroa levels

Q – The hive I lost was due to high varroa levels. Even with treatments in July and September (it was a purchased nuc in late April) the varroa levels rebounded quickly, although the treatments knocked the levels down to below 3 per 100.

A – Thanks for doing survey. You commented that you lost 2 hives to high varroa even though you treated in July & September. The treatments knocked mite level down. I wish we knew what was gong on – best guess is virus epidemic took hives down? We have no treatment for virus so we go after vector (mites). If we knock mite numbers down that should reduce the epidemic of virus! Others are stating same thing – the last couple of years. Mite controls bring numbers down in Aug/Sept but colonies still are lost. NOT SURE WHAT IS HAPPENING.

Posted in Uncategorized

Warre forum link

In the Education section, the other source of great information is the Warre forum hosted by David Heaf

RESPONSE – Thanks for sharing. We have little local expertise on Warre hives and because the management and hive are so different from movable frame Langstroth we need a good source of information. Here is a link as suggested http://www.bee-friendly.co.uk/

Guest Blog “COMMON CAUSE OF WINTER DEATH IN NORTHERN CLIMATES”

COMMON CAUSE OF WINTER DEATH IN NORTHERN CLIMATES

HTTPS://BEEINFORMED.ORG/2016/03/08/WHY-DID-MY- HONEY-BEES-DIE/

By Meghan Milbrath, Michigan State University Extension, March 8, 2016

Guest Blog

Beekeepers in northern climates have already lost a lot of colonies this winter. While official counts won’t be recorded for a few months, some trends are starting to emerge. One of these trends is a specific type of colony death. In Michigan, I’ve received so many calls describing the scenario below, that I can describe the deadout before opening the hive, or before the beekeeper describes it over the phone. While I may impress some with these predictive powers, the frequency of these types of losses indicates a real epidemic that is affecting honey bee colonies in northern states.

Characteristics of the common early winter death in northern states:

1. The colony was big and looked healthy in the fall

2. A lot of honey is left in the top supers

3. The cluster is now small, maybe the size of a softball

4. There are hardly any bees on the bottom board

5. Near or just below the cluster is a patch of spotty brood – some fully capped, and some with bees dying on emergence (heads facing out, tongues sticking out).

6. If you look closely in the cells around the brood, you will see white crystals stuck to the cell walls, looking like someone sprinkled coarse salt in the brood nest.

AND

7. You don’t have records showing that varroa was under control.

Sound familiar?

We see this classic set of symptoms over and over in the states with a proper winter. A big colony that seems to just shrink down and disappear. Many people want to use the term colony collapse for this type of death, and while collapse is a good descriptor of what happens, this is not true colony collapse disorder. This is death by varroa associated viruses.

How does it happen?

1. The big colonies –While beekeepers are often surprised that their big colonies are the ones that are gone first, it makes perfect sense in terms of varroa growth. Since varroa mites reproduce in capped brood, the colonies that made the most brood (i.e. got the biggest) are the ones most at risk of having a high population of varroa. Colonies that swarmed, or didn’t take off, or even fought a disease like chalk brood are less at risk from high varroa populations, because they didn’t consistently have large amounts You should have good notes indicating cluster size going into winter, but even if you don’t, you can see the large circle of food eaten by a large cluster.

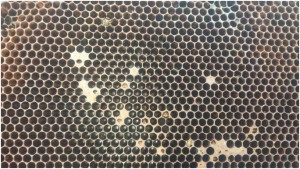

This colony had a large brood nest (indicated by the dark comb in this frame from the top deep box), and a large cluster going into winter (indicated by the large amount of honey that is eaten away where the winter cluster started). Varroa were never monitored or managed in this colony, and it was dead by February, if not sooner. (Photo by Meghan Milbrath)

2. Lots of Honey – Lots of honey means that the colony died fairly early. Colonies with high levels of varroa, they tend to die fairly early in the season (before February), leaving lots of honey behind. Once the bees are stressed and in cluster, the viruses take their toll very quickly. In some cases the colony will even abscond in fall, or be dead before winter really hits.

The colony shown above had a third deep box that was filled with capped honey, indicating that the bees died early, and starvation was not the culprit.

3. Small cluster – Varroa levels peak right when the winter bees are getting formed. The bees that emerge from varroa infested cells are weakened, and more importantly, are riddled with viruses. Varroa mites are notorious for carrying deformed wing viruses (DWV), but are known to transmit many more. When bees are close tight in a winter cluster, the viruses can spread very quickly.

In our colony, the cluster was only the size of our hand – some bees had their heads stuck in the cells, trying to stay warm, others had fallen between the frames.

4. No bees on the bottom board – When a colony starves, the bees just drop to the bottom board, and you end up with a pile of dead bees in the hive. When bees get sick with viruses and other pathogens, however, they often will fly away. Sick bees by nature leave the colony to die in the field, an act designed to prevent pathogen transmission in the colony. When most bees are sick, they either fly away, or are too weak to return after cleansing flights. An early fall illness means that a lot of the bodies probably got removed by workers too.

The colony we examined had only a few bees left on the bottom board (1-2 cups). We didn’t see a lot of varroa, but there had been some robbing, so wax cappings covered a lot of the board.

5. Patch of spotty brood/ Bees dying on emergence – When a colony succumbs to varroa associated viruses or parasitic mite syndrome (PMS), we see a lot of effects in the brood. Unlike American Foulbrood (AFB), which attacks the larvae at one particular stage, PMS will affect developing bees at many stages of development. It is one of the only diseases where you see bees dying right as they emerge.

Note the bee in the upper left is fully formed, and died on emergence. You can often see frozen/melted larvae along with dead pupae. Many beekeepers instantly suspect AFB, but AFB infected colonies usually will not be large and have produced a lot of honey going into the winter. (Photo by Meghan Milbrath)

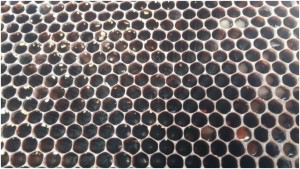

6. White crystals in the brood – Around the cells where the brood died (the last place of the brood nest), you will often see white crystals stuck to the walls of the cells. These are dry (not suspended in liquid like crystalized honey), and are the crystalized pee of varroa. Varroa mites defecate in the cells, and the resulting guanine crystals are left behind, and visible to the naked eye.

Cells on the right hand side of this photo contain small crystals of guanine acid, indicating varroa defecation. Notice the dry, irregular shape, and that they appear stuck to the walls on the cells. Some cells on the left hand side of this photo contain crystalized sugar. Note the wet/liquid appearance, and that it is largely in the bottom of the cell. (Photo by Meghan Milbrath)

7. No records that varroa was under control. Notice that this says ‘varroa was under control’, and not that ‘the colony was treated’. You may have applied a treatment, but it may have been too little, or (more likely) too late. This year was a particularly difficult year for this, because in Michigan we had a really late summer – it stayed warm enough for beekeepers to go into their hives well into October. Many beekeepers took the extra time to put on a varroa treatment, thinking that they were lucky to get one in. While that treatment could help the bees for next season, it was too late for this winter. September and October treatments would have been applied after varroa had gotten to their winter bees. Winter bees are born in the fall, and with their special fat deposits that allow them to live through the winter months, they are the one who carry the colony to the next season. If the winter bees have already been infected with viruses, the damage is done. No amount of treatment or varroa drop would bring the colony back.

The only way to know that you have varroa under control is to monitor using a sugar roll or an alcohol wash. Just looking at the bees does not work; varroa mites are so sneaky, that you rarely ever see them, unless the infestation is out of control, and it is too late. Many beekeepers say that they never see varroa in their hives, so they don’t think that they have a problem. In fact, a varroa infested hive can actually look like it is thriving.

Underneath the lovely brood cappings, and away from our view, the mites are reproducing and biting the developing bees. The colony can look fairly healthy until the mites reach a threshold, and the colony succumbs to disease. By the time you see parasitic mite syndrome, or see varroa crawling on bees, it is often too late for that colony (especially if winter is just around the corner). Getting on a schedule of monitoring and managing mites will give you peace of mind that your healthy looking colony is indeed healthy.

The silver lining

If the above scenario is familiar, don’t despair. First, you are not alone. Many beekeepers got caught off guard with varroa this year. They didn’t realize how bad it was, or got thrown off by odd weather patterns. Second, when the bees die, the varroa mites die too. We don’t yet have evidence that the viruses would stay in the equipment, so you can reuse your old frames. The honey that is left can be extracted to enjoy (if you didn’t feed or medicate), and frames of drawn comb can be given to new colonies. Most importantly, if you recognize the above scenario in your colonies, you now have more knowledge as to what is harming your bees, and you can take positive action. You have time for this season to develop a strategy. Monitor your varroa mite levels using a sugar roll kit (available at pollinators.msu.edu/mite-check/ or at Mann Lake), read about integrated pest management for varroa, and make a commitment to prevent high mite levels this year before your winter bees are developing. This is going to be the year!

Meghan Milbrath, Ph.D.

[email protected] /517-884-9518

Meghan Milbrath is a beekeeper and the coordinator of the Michigan Pollinator Initiative at Michigan State University. She performs pollinator related research and extension work, and works with beekeepers and stakeholders around the country. She started keeping bees over 20 years ago, and currently owns and manages a The Sand Hill apiaries, where she manages 150-200 colonies for queen rearing and nuc production