by Dewey M. Caron

Varroa mites continue to change the beekeeping landscape. In the ‘good ‘ol days’ it was far easier to start a bee colony and keep them alive than today. After introduction of the varroa mites into the U.S. (1987), there was an unprecedented rapid approval of tau-fluvalinate pesticide by EPA for in-hive mite control. And the resulting miticide Apistan® worked very well in killing mites.

Unlike the tracheal mite, varroa mite did seem to be controllable at first. Beekeepers changed from a chemophobic attitude about pesticides (chemicals around bees were to be avoided – ‘feared’) to chemophilic (chemicals were tolerated/useful – ‘liked’). But all too soon we began to understand the ‘unintended consequences’ to the hive environment and our honey bees when we began putting a pesticide inside a bee colony. We seriously contaminated our beeswax with the miticide and mites developed resistance to this chemical within several years meaning it became ineffective.

The subsequent generation of pesticides (Coumaphos – an organo-phosphate compound, developed to kill enemy soldiers in war-time) and Hivestan (fenpyroximate pyrazole) were even more detrimental in the bee environment and mites even more rapidly acquired resistance. Current sole synthetic miticide Apivar (amitraz), although generally not as harmful to bees or their environment, is showing signs of mites developing resistance to it as well.

A mite management concept has begun to creep into our language – IPM, Integrated Pest Management. IPM fits with the concept that it is not practical (impossible) to kill every last mite in our colonies (nor possible to keep them out) but rather we should seek to manage the mite population at a level that is minimally damaging. As we manage the honey bee population for gain, we need to incorporate and integrate mite management – an integrated control program.

The question beekeepers need ask is NOT does my colony(ies) have mites? but rather HOW MANY mites does my bee colony(ies) have? To determine how many means varroa mite monitoring, a crucial first step of an IPM management program. When we determine HOW MANY we become better informed bee colony stewards. HOW MANY helps us know the risk of doing nothing and helps us target seasonally appropriate control(s) to slow mite population growth with goal of keeping mite populations at less damaging, more tolerable levels.

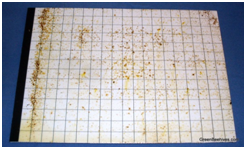

One early (alternative) non-chemical mite control treatment was use of Screen Bottom Boards. With widespread adoption of screen bottom boards in place of solid boards, a whole industry developed incorporating mite monitoring  sticky boards beneath the bottom screen (one example shown at right). There were attempts in Georgia, Washington State, and by myself in the Mid-Atlantic States, to determine how best to count fallen mites with a sticky board and how to interpret the numbers – a threshold was developed.

sticky boards beneath the bottom screen (one example shown at right). There were attempts in Georgia, Washington State, and by myself in the Mid-Atlantic States, to determine how best to count fallen mites with a sticky board and how to interpret the numbers – a threshold was developed.

This threshold number has been modified as we have learned that mites vector and enhance viruses. Initially 50 mites per days was a threshold. The number has been lowered, initially to one per hour (24/day) and now one per every 2 hours the mite board is in use (12/day). If boards collect more mites the risk to the colony increases with higher mite fall.

Currently 79% of beekeepers responding to the PNW winter colony loss survey indicate they use a screen bottom board as a mite control technique. (see Screen Bottom Boards – a 4 year perspective Report posted to www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com). However after 4 years of survey data for Oregon and Washington small-scale beekeepers, a clear picture emerges that screen bottoms aren’t very useful in reducing mites:

The four year average – 41.3% winter loss level of those using SBB vs 43.4% loss level for those not using SBB – represents a mere 5% gain (i.e. improved winter colony survival) with screen bottom boards.

A constant discussion has been should the colony bottom be left exposed during winter or should the screen be closed as a winterizing management? Closure was often achieved by using a mite monitoring board with the screen bottom. Four years of survey data tallying the always and sometimes left open response compared with the closed in winter response reveals:

10 percentage point difference in favor of closing the SBB over the winter period (i.e. less winter loss if the board is closed in the fall.)

How Best to monitor Mites

Beekeepers generally have available 5 methods to assess the mite population in their colonies. Sticky boards were initially considered a good tool to do whole  colony mite number assessment. However there are problems in use of this tool. Foremost with sticky boards, when used to asses mite colony population, was and remains how to quickly and accurately count the mites on the boards. Mites are tiny, sticky boards collect lots of debris and ants and other scavengers may remove fallen mites.

colony mite number assessment. However there are problems in use of this tool. Foremost with sticky boards, when used to asses mite colony population, was and remains how to quickly and accurately count the mites on the boards. Mites are tiny, sticky boards collect lots of debris and ants and other scavengers may remove fallen mites.

Natural mite fall (i.e. mite drop not enhanced with use of a control), can vary a great deal for a variety of reasons. Size of colony makes for variation, time of season, degree of auto-grooming behavior by bees and also how the boards are inserted and how long they are left inside adds to more variation. Efforts to reduce counting by sampling only a portion of the drop proved impractical as a large portion of a sticky board still needs to be counted to obtain an accurate assessment.

Sticky bottom boards are useful in providing a quick ‘snapshot’ as to whether there are few or many mites in a colony. It can help validate the effectiveness of a control that was used if utilized post-treatment. They are not adequate to provide a precise estimate of mite population without accurate, time-consuming counting and multiple, repeated sampling.

BOTTOM LINE: Screen Bottom Boards are not an effective mite monitoring method

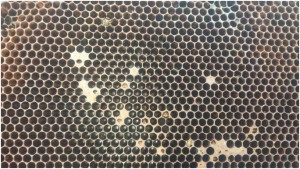

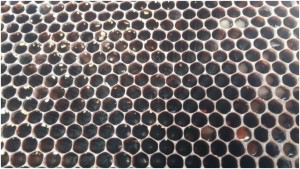

More problematic as monitoring tool is using a visual method of counting number of mites. This is used for colony worker adults or number of mites within drone brood cells. The phoretic mites, (i.e. those on the adults), are highly mobile and some of the mites are deeply embedded between body segments to enable them to feed on adult hemolymph and fat body. Their deep reddish color and compact flattened body means they blend into the adult color patterns.

The counting of reproductive mites within drone cells has proved to be highly variable. The reproductive female mites are easier to see on the white drone pupae (compared to adult bodies) and sampling of drone pupae within capped cells with use of a cappings scratcher is easy. However numbers are not easily correlated to the actual population level within the colony. One serious drawback with this method is during the fall months, when mite population assessment is most critical, there are often no or few capped drone brood cells available to assess.

BOTTOM LINE: Visual mite monitoring methods are not effective enough

Thus today we believe counting of the mites on the adults by washing the adults to remove their mites (the feeding mites as well as those ‘riding’ the adult) to be the “best” method. Our two recommended methods are the use of powdered sugar or using alcohol (or a non-sudsing soap). Use of powder sugar allows return of adult bees back into their colony whereas the alcohol/soap kills the sampled bees. See Tools for Varroa Guide on website www.honeybeehealthcoalition.org

Generally a sample size of 300 adults, collected from a brood frame, is recommended. The adult bees can be collected directly into a wide-mouthed sampling jar, previously marked (by sample counting) to indicate 300 bees or the brood frame can be shook into a bucket or plastic container and a ½ cup size measuring cup filled with the bees to dump into the sampling jar. The solid lid of the sample jar is replaced by a 5-mesh screen.

If using powder sugar, a generous amount of powdered sugar (confectioner’s sugar) is sifted onto the sample and the jar vigorously shaken for a minute to thoroughly distribute the sugar and then left to stand for a minute or more to allow heat to build up in the 300 bees. If alcohol is used, add enough iso-propyl (rubbing) alcohol to cover the bees. The liquid is swirled and the bees thoroughly washed for at least a minute. DO NOT RUSH SAMPLING. The mites between the body segments of bees need to separate from their host’s body to get an accurate count. See accompanying photos.

USING powder sugar mite monitoring Using alcohol wash mite monitoring

The sample jar with powdered sugar is then inverted and excess powdered sugar shaken out, along with the mites that had been on the adults. With the alcohol/soap, the mites will be in the liquid portion which can be poured from the sample through a filter, such as a coffee filter, for counting or simply counted in the bottom of liquid with adult bees held above the liquid at base.

The number of mites washed/sugared from the bee bodies is then converted to per cent number of mites for 100 bees (6 mites on 300 adults = 2% for example). The ‘threshold’ for decisions on continuation or initiation of control is currently 2-3% – this number too has been steadily decreasing. Some beekeepers like to keep the number below 1%. Repeat sampling can be done to confirm accuracy. When the sample is below 2-3% monitoring should be repeated to confirm mite population remains at a low level.

BOTTOM LINE: Washing adults collected from a brood frame using powdered sugar or alcohol/soap is the faster and most accurate mite monitoring method for assessment of mite population in colony

In 4 survey years the percent of OR/WA individuals using sticky boards as their monitoring tools has steadily decreased (from 37% of individuals using them in 2015 to currently 25% of respondents using them in 2018 survey response) while alcohol wash as a monitoring method has increased from 5% of reported use in 2015 survey to 14% in most recent survey. Use of powdered sugar to monitor mites has also steadily increased although more modestly. These trends are shown in graph below for 4 survey years.

With our pnwhoneybeesurvey we ask percentage of OR hives monitored for mites, whether sampling was pre- or post-treatment or both and, of the 5 possible mite sampling methods, what method was used and what month(s) was it employed. 184 individual respondents (63%) said they monitored all their hives. When those individuals monitoring all their colonies was equated to the loss they reported, the loss rate was 38. Sixty-one (22%) individuals reported no monitoring and when paired with their loss had a loss level of 49% , 9 percentage points higher [43 individuals reported monitoring some of their colonies; they had a 26% loss]. Numbers are shown in Figure below.

Comparing the last 2 survey years there was a lower loss level, better winter survival difference of 8 percentage point lower losses (48.5% no monitoring vs 40.5% loss total monitoring all colonies.) This means a 17% advantage.

In the 2017-18 season, 68% of Oregon individuals used more than one sampling method. 32% of individuals used a single monitoring method (23 individuals used alcohol wash, 19 used sticky board and 18 powder sugar). Of those using multiple sampling methods, 39% used 2 methods, 24% used 3, 5% (10 individuals) used 4 and 1 individual used all 5. Sticky boards were used 108 times, at least once in each month. Alcohol wash was used the fewest times, 51 total and only 11 months with little utilization in an additional 3 months. Most sampling to monitor mites was done in July – September, as might be expected since mite numbers change most quickly during these months and results of sampling can most readily be used for control decisions. See graphic below illustrating monthly use for each of the 5 sampling methods.

Summary: Monitoring colonies for mites helps inform the beekeeper on HOW MANY mites (size of mite population) and with repeated sampling if the number is increasing or remaining level. This can key a decision on risk of doing nothing about mites (i.e. not using a mite control) and also can help confirm that a treatment (when sampled post-treatment) was effective in reducing the mite population. Of the several sampling methods the recommendation is to wash adult bee bodies, collected from the brood area of the colony, with powdered sugar or alcohol/soap. Mite number in sample should be below the 2/3% level to confirm there is a low risk of mite damage to the colony. Consult the Tools for Varroa Guide information on the website www.honeybeehealthcoalition.org for further information on sampling, the meaning of mite sample numbers and for information on mite control.