** Looking for a report in your specific region? Refer to the Individual Club Reports page.

** Scroll down to see the Washington Backyard Beekeepers Winter Bee Loss Report, 2024-25 or click here to view Washington as PDF.

Winter Bee Losses of Oregon Backyard Beekeepers for 2024-2025

by Dewey M. Caron

Click here to view a PDF of Oregon report.

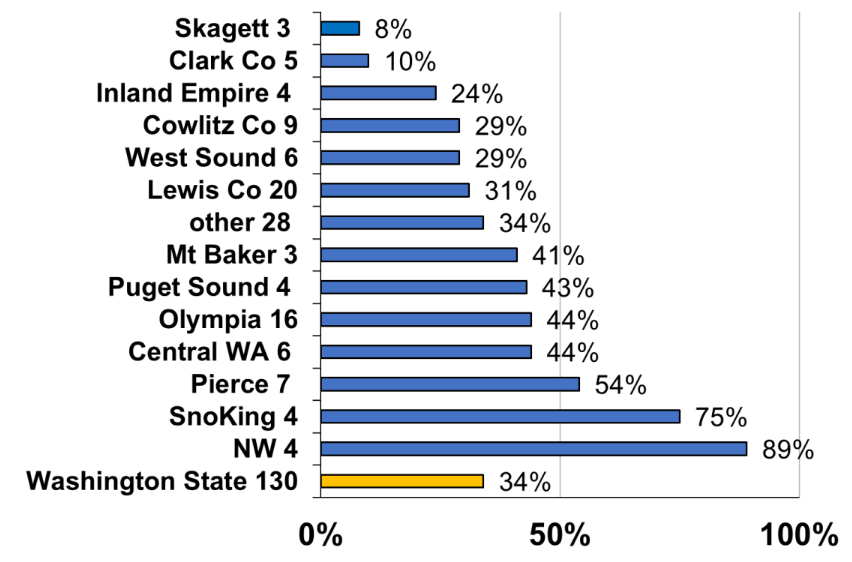

Overwintering Overwintering losses of small-scale Oregon backyard beekeepers remained low this season (25.5%) following the record low 20% the previous winter of Oregon hobbyist/backyard beekeeper surveys. – www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com. Herein we discuss the data provided by 251 Oregon beekeepers, an increase of 80 from the previous year and 31 below the average response rate of 282 respondents for the last 6 years. Overall loss rate was 25.5%. Results of the 130 Washington respondents completing surveys (slightly above the average response rate of the last 6 years of 120) are included in a separate loss report. The Washington average loss was 34%, just a bit above 31% loss rate last year.

State/Club Losses

The Bee club results of 12 local Oregon associations are shown in Figure above. Individual colony numbers ranged from 1 to 49 colonies in Oregon (average 5.7 colonies same as last year; medium number = 4 colonies, also same as last year). The number of respondent individuals are listed next to the association name. The bar length is the average club loss percentage for the year.

Overwinter losses of members of the 12 clubs varied from a low of 10% for SOBA (11 respondents) to 50% for LBBA (16 respondents). Losses for clubs (and number of respondents) not shown in Figure are: Coos Co (3) 7%, Douglas Co (2) 9%, Eastern OR (3) 47% and Klamath Basin (3) 87.5%. The 5X extreme range (10 to 50%) loss of the dozen clubs with the largest respondents is more extreme than in previous seasons (previous range 4X). Approximately 80% of respondents are roughly along the I-5 corridor between California and Washington.

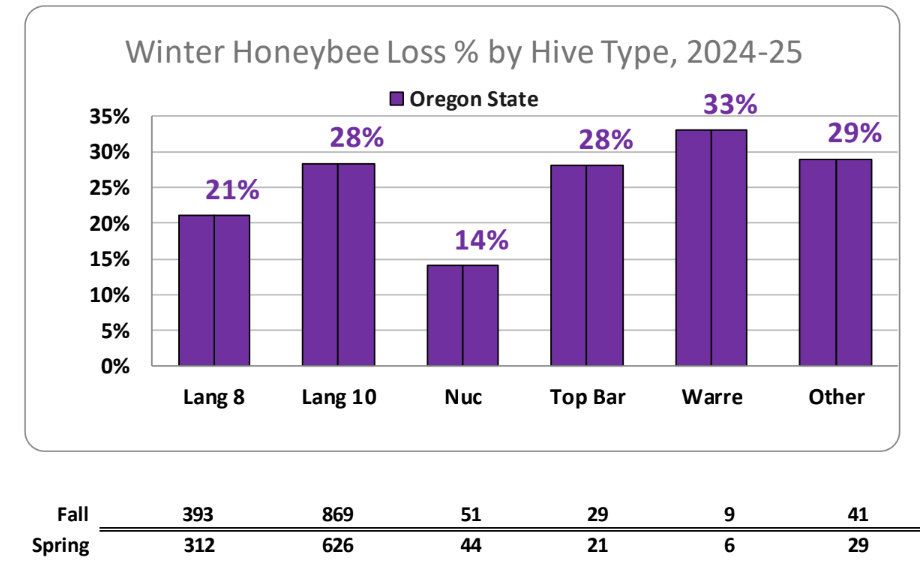

2024-2025 Overwinter Losses by Hive Type

The loss statistic was developed by asking number of fall colonies and surviving number in the spring by hive type. Respondents had 1393 fall hives (405 more compared to the respondent number last year) of which 1038 survived to spring (355 lost), equating to a 25.5% loss (74.5% survival rate). This was 5.5 percentages points poorer survival compared to the previous winter loss rate. It was lower than the 15-year average loss rate by 10.1 percentage points.

All but 70 were 8-frame, 10-frame Langstroth hives, nucs or (15) long hives. There were 51 fall nucs (13.7% loss rate). Among non-traditional hive types were 29 top bar hives (27.6% loss) and 9 Warré hives (33% loss). Other hive types in addition to long hives included 8 Layens, 1 AZ, 1 Valkyrie; 2 tree; 15 were not identified to type. Of 41 total other, 12 were lost for 29% loss level.

The loss rates of Langstroth 8 and 10 frame hives over the past 9 years have averaged 34.3% for 8-frame Langstroth hives and 38.7% loss for 10-frame hives respectively. Nuc losses are typically higher than losses of 8 or 10-frame Langstroth hives but were lower this year. The Nuc 9-year average loss is 40%. This year’s Top Bar hive loss of eight colonies (27.6%) is below the 9-year average top bar hive loss of 48%. The 2024 Warré hive loss rate of 33 % is below the 8-year average of 40%.

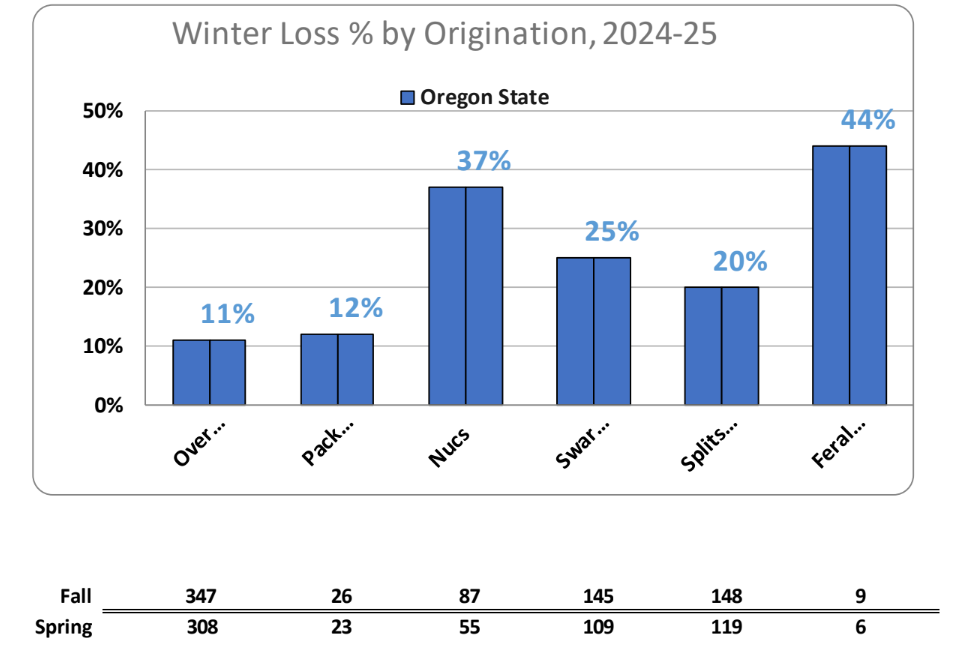

2024-2025 Loses Based on Hive Origination

The survey asks respondents to characterize their loss by hive origination. This year respondents could FAST TRACK and 54% of respondents did not respond to this survey question. The results of respondents are graphically presented below. Overwintered colonies obviously had the best survival (11%) as is normally the case and it was well below the 31.9% average overwinter loss average for the past 7 years. Packages also had excellent survival 12%. Nuc losses of 37% were below the 7-year average of 52.6%. Swarms and splits had good survival. Only 9 feral colonies were reported.

Figure 3

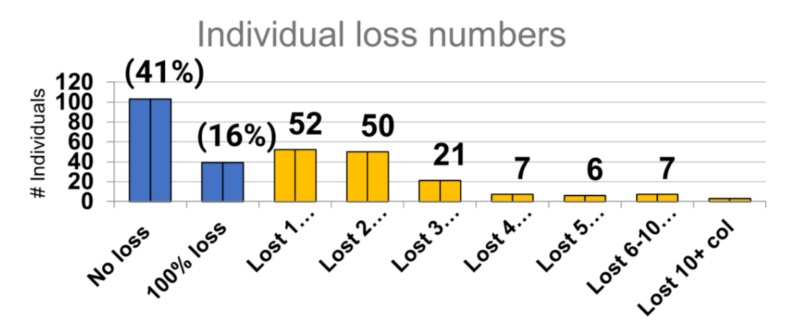

2024 -25 Individual Hive Losses

Forty-one percent (103 individuals) of Oregon respondents had NO LOSS overwinter (total of 470 colonies), a decrease of 6 percentage points and increase of 22 individuals compared to last year. Fifteen and half percent (39 individuals – 88 colonies) lost 100% of fall colonies. Figure 4 below shows loss by individuals. The loss of a single colony (by 52 individuals) represents 35% of total individuals reporting loss. Three individuals (2%) lost ten or more colonies. The highest loss by a single beekeeper was 12 colonies. Numbers shown in figure 4. Loss numbers are reflective of the fact that the median number of bee colonies of backyarders was three colonies.

Individuals with 1, 2 or 3 colonies, 132 individuals, lost 120 colonies = 34% loss level; individuals with 4 to 6 colonies, 216 total colonies, lost 22%. Fifty-six individuals with 4 to 6 colonies lost 27.5% of their colonies. The 28 individuals with 7 to 10 colonies lost 28% of their colonies as did the 21 individuals with 11 to 19 colonies. The 11 Individuals who had 20+ had 19% loss level. The two individuals with greatest colony numbers 34 and 49 colonies.

Figure 4

Survey respondents are primarily small colony number beekeepers – 52.5% had 1-3 colonies (132 individuals) but they vary considerably in their years of beekeeping experience. Looking at losses by colony numbers, the 58 of the 132 individuals who had 1-3 colonies, had 1-3 years of experience. They lost 50.5% colonies. Maximum was 20 years experience for 1 colony beekeepers, 21 years experience for 3 colony beekeepers and 47 years experience for 2 colony beekeepers.The 37 individuals who had 4-9 years experience had 38% loss. The 20 individuals who had 10-19 years experience had 32% loss level and those individuals with 20+ years experience had 16% losses.

By years of experience, the 72 individuals who had 1 to 3 years bee experience (29% of total respondents) had 33% colony loss level and the 64 individuals with 4-6 years experience (25.5% of

survey takers) had a 24% loss level. Individuals with 7-9 years expereince, 17,5% of total respondent number, had 23% loss level. The 53 individuals with 10-19 years experience (21% of respondents) had a 22.5% loss level and those 18 individuals (7% of respondents) with 20+ years experience had a 31.5% loss level. Thus the 48% of survey respondents with 1-6 years experience had an 26.5% loss level and the 52% that had 7+ colonies had 32.5% loss level.

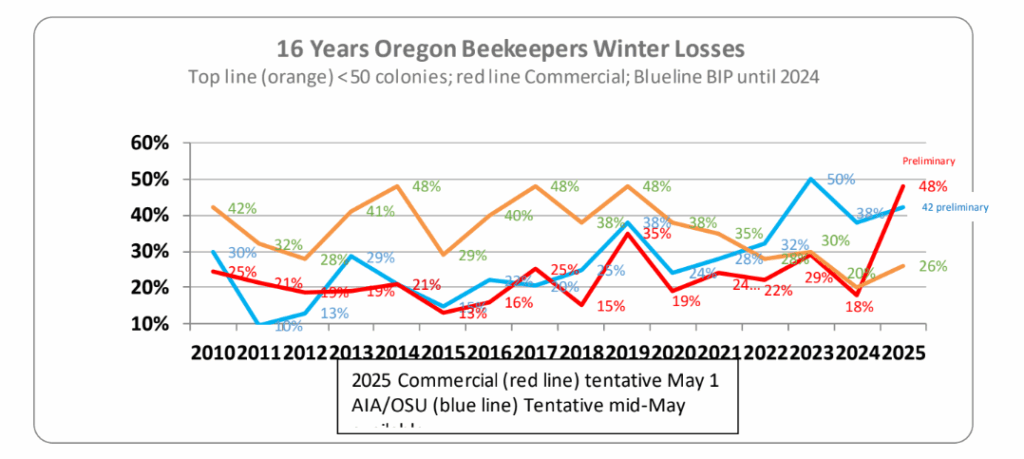

Overwinter Losses the Past 16 Seasons

Comparison of the annual losses of backyarders with commercials is shown in Figure 5. The commercial losses are obtained from a different paper survey distributed by Oregon State University. The number of commercial respondents (5 commercial and 2 sideliners) is preliminary as of May 1; reported losses on only 22,400 colonies (NASS estimated colony number in Oregon (2022) =76,000.

This preliminary loss rate is 47.8%. Average backyard losses =36.3% loss and 15-year commercial/semi-commercial loss = 21.4%. The BeeInformed average (14 years) =25.4%; in 2024 the national survey was conducted by a consortium of Apiary Inspectors of America/Auburn University and Oregon State University. The 2024 winter loss was 37.7%: preliminary overwinter losses for 2024-25 = 42%

Some Other Numbers

Thirty individuals (12%) had more than a single apiary location. The loss level at 2nd apiary was same in 16 locations, had lower losses in 8 and in 6 it was poorer survival. Six individuals had a 3rd apiary site with 2 reporting the same survival, 3 better and 1 poorer. Seventy-seven-point seven percent (77.7%) of respondents (same as last year) said they had a mentor available as they were learning beekeeping. Seventy-eight individuals (31%) had more than one hive type, same percentage as last year but 24 more individuals. And, finally, 12 individuals (5%) moved their bees. One move was sale/gifting of hives, one was due to owner move, one was due to allergy of owner where bees were sited, 3 were for pollination, 1 for better honey, 1 was for better winter site, 1 was a hive gift, and 3 involved new locations of beekeeper. Distances were within the same property up to miles away (for relocation and pollination).

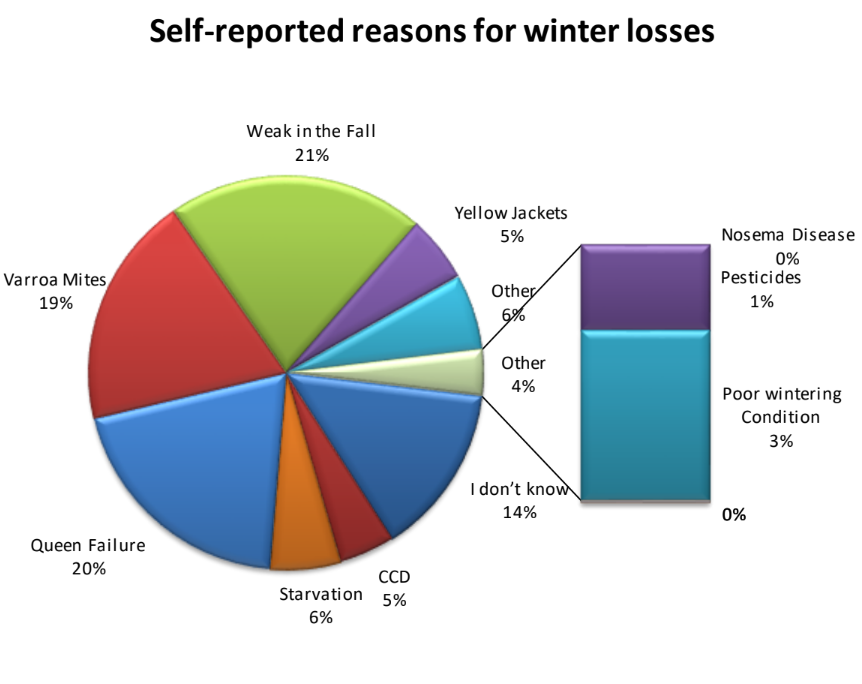

Perceived Colony Death Reason and Acceptable Level

The survey asked individuals that had colony loss (99 individuals listed no loss) to estimate what the reason might have been for their loss (multiple responses were permitted). Thirty-four listed don’t know. There were 167 total listings, 1.85/individual. Queen issues (48), weak in the fall (51) and varroa (46 individuals) were most common. Starvation, 14 selections and yellow jackets, 13 respondent choices, along with CCD (11 selections) were three additional double-digit choices. Among the 15, 3 indicated absconding, 2 indicated extreme cold and rain, another cited lack of attention (it was termed beekeeper error), one each said poor stock, robbing, tracheal mites, use of Formic Pro, entrance clogged, moisture, uniting problem and virus. See Figure 6 graph below.

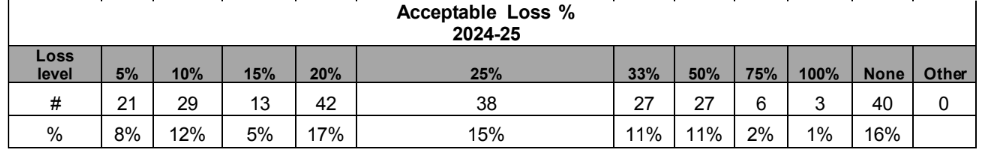

Acceptable loss: Survey respondents were asked the reason for loss. Forty respondents (16%) indicated zero (no loss). Twenty percent was the medium and most common choice (outside of zero) choice, as has been the case for several years. Fourteen percent said 50% or greater was an acceptable loss level; six said 75% and 3 said 100% loss levels acceptable. See Table below.

Why do colonies die?

There is no easy way to verify reason(s) for colony loss. Colonies in the same apiary may die for several reasons. Examination of dead colonies is at best confusing and, although some options may be ruled out, we are often left with two or more possible reasons for losses. A dead colony necropsy can be of use. Opinions vary as to what might be an acceptable loss level. We are dealing with living animals which are constantly exposed to many different challenges, both in the natural environment and the beekeeper’s apiary. Individual acceptable choices varied from zero to 100%, with a medium of 20%.

The major factor in colony loss is thought to be mites and their enhancement of viruses especially DWV (deformed wing virus), VDV (Varroa destructor Virus – also termed DWV B) and Israeli and chronic paralysis viruses. But we do not have a test for these viruses. It was interesting that weak I the fall and queen problems were the most frequently indicated along with varroa mites as leading reasons for loss.

Declining nutritional adequacy/forage and diseases, especially at certain apiary sites, are additional factors resulting in poor bee health. Yellow jacket predation is a constant danger to weaker fall colonies. Management, especially learning proper bee care in the first years of beekeeping, remains a factor in losses. What effects our changing environment such as global warming, contrails, electromagnetic forces, including human disruption of them, human alteration to the bee’s natural environment and other factors play in colony losses are not at all clear.

There is no simple answer to explain the levels of current losses nor is it possible to demonstrate that they are necessarily excessive for all the issues our honey bees face in the environment. It was encouraging to see from survey responses that overall losses this past year, 25.5%, were still at a low level. More attention to colony strength and the possibility to mitigate colony weakness in the fall will help reduce some of the losses. Effectively controlling varroa mites will help reduce losses.

Colony Managements

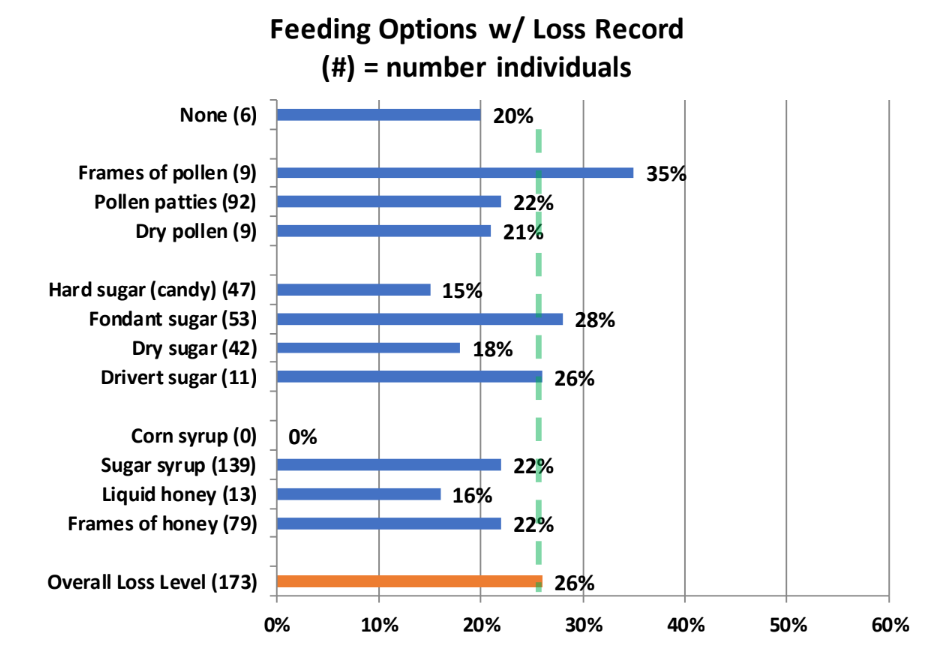

We asked in the survey for information about some managements practiced by respondents. This year individuals could FAST TRACK through the electronic survey and not answer the questions on management. The survey inquired about feeding practices, wintering preparations, sanitation measures utilized, screen bottom board usage, mite monitoring, both non-chemical and chemical mite control techniques and queens. Respondents could select multiple options and there was always a none and other selection possible. The report seeks to compare responses of the current winter season with previous survey years. The percentage of individuals that opted to FAST TRACK are indicated for each section. For example, 78 individuals or 31% Fast TRACKED this first section on Feeding, Winterizing and Sanitation.

FEEDING: Oregon survey respondents checked 507 feeding options = 3.4/individual (same as last year). Twenty-one individuals (12.5%), other than the 6 who indicated no feeding, selected a single choice and had 16% loss, 38 (23% of respondents) indicated 2 choices (31%, loss), 53 (32%- the greatest number and medium) indicted 3 choices (they had 23% loss), 31 individuals (18.5%) had 4 choices with 23% loss, 15 (5.5%) had 5 choices (21 % loss), 6 individuals (3.5%) had 6 choices also had a 21% loss. And two individuals with 6 & 7 7 selections had 28.5% loss. There were 7 total who listed selections; 5 of those indicated using hive alive – they had 9% loss, the other two added peppermint (no loss) and the 7th indicated use of MegaBee but loss was 75%.

The managements with number of individuals making that selection are in ( ) in Figure 10; bar length indicates loss level of individuals doing this management. Those bar lengths to left of 26% green dashed marker had better survival, while those to right had greater loss level. Six individuals (1 more than the previous year – but recall only 70% of total respondents submitted data) said they did NO FEEDING. They had 25 fall colonies, lost only five for a 20% loss, the best survival of any group for feeding management. For individuals indicating one or more feeding managements, feeding sugar syrup was the most common feeding option of respondents (139 individuals, 83% of respondents who indicated feeding management). Their loss rate was 21.5%, 4 percentage points better than the overall average.

Individuals feeding protein 100 individuals (60% of respondents) had an overall survival rate of 23%. Pollen patty feeders (92 individuals, 55% of total respondents, 3 % fewer than last year) had a 22% loss rate, 9 individuals feeding frames of pollen had 34½% loss and 9 feeding dry pollen reported a 20.5% loss (best survival of the 3 methods of feeding protein). There were 200 instances of feeding non-liquid sugar feeders, 53 fondant feeders and 47 candy feeders. The best survival rates were the 47 candy feeders, only 15% loss. The 42 dry sugar feeders had 18% loss. The 11 drivert and 53 fondant feeders did the poorest of the group, 26% and 28% loss levels respectively.

Summary: Statewide for the last 8 years individuals prior to this year when 31% of respondents FAST TRACKED and did not provide information on this management, who did no feeding had only a 4.5 percentage point higher loss (average 40.5%) i.e. poorer survival, compared to an average loss rate of 35%. This year the 6 individuals doing NO FEEDING had better than average survival (20%). The average percent doing no feeding = 6.5% of individuals – this year it was 3.5% of responding individuals).

Individuals statewide that fed sugar syrup had a 3.8 percentage point lower loss level average for the 8 years; this year it was 4 percentage point lower survival. Those feeding honey (as frames or liquid) had lower loss only during three of the past 8 years. This year it was a four-point better survival; The 13 individuals who indicated feeding liquid honey had a 16% loss rate, a full 10 percentage points better than average survival rate.

Individuals feeding non–liquid sugar (in any form) had lower losses six of past eight past winter seasons. Dry sugar feeders had slightly better or equal survival 7 of 8 past winters and this year, with 18% loss, did better as well; hard candy feeders had improved survival 7 of 8 past winters, including this past winter, with the best survival of all dry sugar feeders at 15. Fondant feeders had better survival four of the eight past winters; it was slightly lower survival this year.

Figure 7

For individuals feeding protein, the protein patty users have had better survival 6 of 8 years (this year losses were four percentage points better than average); dry pollen feeders had better survival in three of the past eight years and this year had the second best survival level of all protein feeders at 22% this year.

It is clear that feeding, while a beneficial management, does not, by itself, significantly improve overwintering success. Those doing no feeding have generally had a higher loss with an 8-year average of 4.5 percentage points higher loss than average, but this year was an exception.

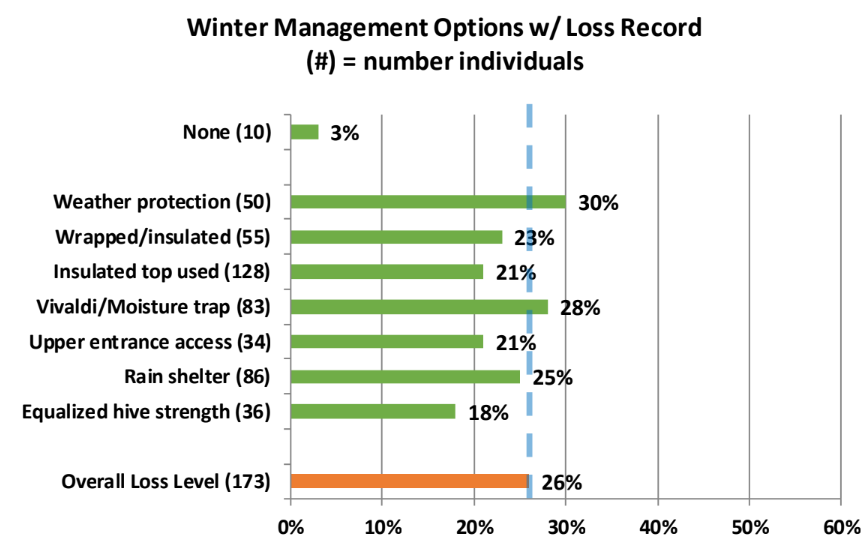

WINTERING PRACTICES: We received 162 responses (1/individual down from 2.5/individual last year) about OR beekeeper wintering management practices (more than one option could be chosen). Ten individuals (6 %) of the respondents indicated doing none of the several listed wintering practices; last year the same percentage of individuals had an elevated 44% winter loss, more than double overall loss but this year they lost only a single colony of 35 in the fall – a 3% loss, 97 % survival rate. For those indicating some managements, 26 individuals (16%) did one single thing, (30.5% loss), 44 respondents (27%) did 2 (17% loss) – this was the largest selection and also the best survival rate, 40 individuals (median number) did three of the winter managements (27% loss), 32 did 4 (24% loss), 16 did 5 (20% loss) and 4 did 6 or 7 with 31% loss. Doing more did not ensure overwintering success.

The most common wintering management selected was insulated top (128 individuals, 78.5% of respondents, an increase of 17.5 percentage points from the previous year, which was 9 percentage points greater than the year before – it seems individuals are listening to past results and speakers who are saying the “key” to better wintering is top insulation of at last 5 r value) – they had a 21% survival level , 4.5 percentage points better than the average. Equalizing colonies in the fall had the best loss level of 18% (36 individuals.) Venting the upper box (83 individuals, 27.5% loss) and sheltering colonies form wind/water (50 individuals, 30% loss) were the two managements that were less successful for improving overwintering success. Figure 8 shows per cent of individual choices and bar length shows percent winter loss of each selection. Bars to left of green dashed line means better survival than overall. Only equalizing (along with insulted top) improved winter survival.

Summary: Over the past seven years individuals that did no winterizing practice (average 10.6% of individuals – recall that 31% of total OR respondents did not responding to wintering management questions when they did FAST TRACK – averaged 41.7 loss compared to 35.2% overall average loss of last 7 years, a 6.5 percentage point poorer survival rate. This year the 10 individuals doing NO Winterizing lost only a single colony of 35 overwintered colonies – a 3% loss rate. I have no explanation why they did so well without any winterizing preparations.

Use of an insulated top winterizing management has improved survival 6 of 7 years (7-year average loss of 28,7%, a 6.5-percentage point improvement); this year it was most common winterizing management (128 individuals), and they had a 4.5 percentage point improvement in survival.

Vivaldi/quilt box and wind/weather protection showed the poorest survival this year as were noted in all past 7 years. Equalizing hive strength was the best management to improve survival over the past three years and this year this management had the best survival with an 18% loss level. Like feeding, winterizing efforts, while useful for some individuals, is not by itself a means to significantly improve wintering success.

Figure 8

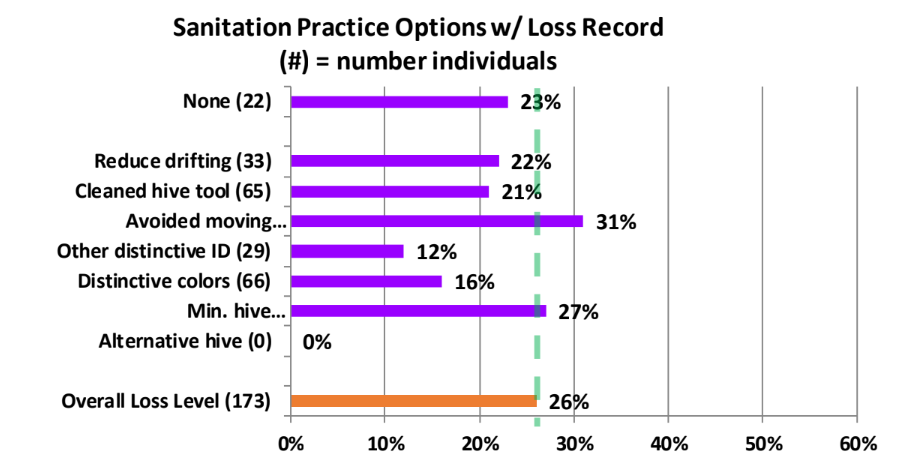

SANITATION PRACTICES: It is critical that we practice some basic bee sanitation (some prefer use of term bee biosecurity) in our bee care to help ensure healthy bees. We received 164 responses for this survey question 1.1/individual (1 percentage point lower than last year). Twenty-two individuals said they did not use any of the six offered alternatives; they had a loss rate of 22% compared to the overall rate – also 25.5%. Over the past five years those indicating doing nothing had a 37.9% percent loss rate, four percentage points higher than the average loss rate of 33.9% over the same time period. This year those doing nothing had a slightly better survival (by 3.5 percentage points). Sixty-three (42 %) individuals had 1 selection with 20% loss, 35 had 2 choices (the median number) with 18% loss level (the best overall), 41 selected 3 managements (33% loss level), 22 had 4 (19% loss level), and 3 made 5 or 6 selections with 30% loss level.

Minimal hive intervention (74 individuals) was the most common option selected, as it has been for the last 4 years. It could be argued that less intervention might mean reduced opportunity to compromise bee sanitation efforts of the bees themselves and that excessive inspections/ manipulations can potentially interfere with what the bees are doing to stay healthy. This option, however, has not improved winter survival; the loss rate for this group the past 7 years was 44%, 10.3 percentage points above the average 7-year 33.7% loss rate. This year the 74 individuals had a 27% loss rate.

Figure 9

The best improvement this year was to paint hive bodies different colors (66 individuals with 16% loss rate) and doing other managements to avoid drifting (29 individuals, 12% loss rate). Avoiding moving frames and reducing drifting have been the two sanitation choices that have demonstrated better average survival the past seven years – 7-year loss rate was 32% for not moving frames which is 1.7 percentage points better survival (the past three years it has been 2 percentage points higher than average) and 28.6% for reducing drifting, a 5.1 percentage point improvement in survival. This year, avoiding moving frames (72 individuals), had slightly poorer survival with 31% loss rate while reducing drifting had a 4 percent-point improvement – 21.5% loss rate by 33 individuals. Overall, sanitation appears to be relatively minor toward improving survival.

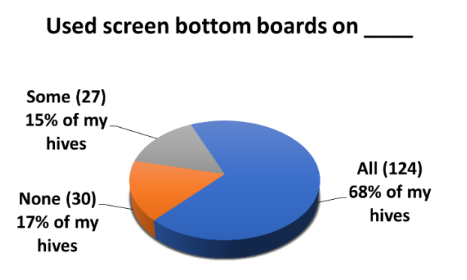

SCREEN BOTTOM BOARDS (SBB)

Although many beekeepers use SBB to control varroa, BIP and PNW surveys clearly point out they are not a highly effective varroa mite control tool. In this recent survey, statewide 29 individuals (17%) said they did not use screen bottom boards – 25% said they used sometime. Average non-use for the last eight years is 16%, vs 84% use, on some or all colonies. Figure 10.

This past overwintering season, the 29 non-SBB users had winter losses of 43 colonies, a 27.5% loss. Examining the eight-year average of SBB use, loss level of the 84% using SBB on all or some of their colonies was 32.2% loss level whereas the 16% not using SBB had loss rate of 35.2%, a 3-percentage point positive survival gain for those using SBB versus those not using them. This year Those using screen bottom boards had a 21.5% winter loss versus those not using them having a 27.5 % loss, a survival advantage of 6 percentage points, minor improvement for overwinter survival.

We asked if the SBB was left open (always response) or blocked during winter. This past season, 71%, 115 individuals, said they always blocked SBB during winter; 16 individuals statewide said they blocked some of the SBBs. Statewide those who blocked always or sometimes had 818 colonies in the fall and lost 176, a 21.5% loss rate. Those 30 who never blocked had a 27.5% winter loss, a 6-point percentage difference. As in past years, there was a slight advantage in favor of closing the SBB over the winter period to improve survival.

Summary: Screen bottom board use has a slight survival advantage. For those using SBB, the advantage appears to be to close, partially or completely, the screen over the winter period.

Mite monitoring/Sampling and Control Management

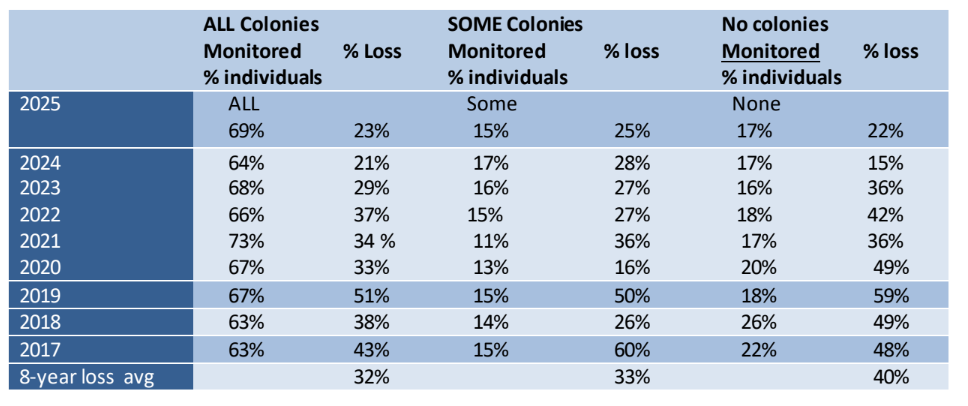

We asked the percentage of Oregon hives monitored for mites during the year 2024 and/or overwinter 2024-25, whether sampling was pre-/post-treatment or both and, of the five possible mite sampling methods, what method was used and when it was employed. Seventy-two respondents did response to this and did not FAST TRACK around the question. 124 individual respondents (68.5%), said they monitored all their hives. The losses of those individuals monitoring were 23 %. Thirty individuals (16.5%) reported no monitoring; they had essentially the same rate of 22% loss. 27 individuals reported monitoring some of their colonies; they had a 25% loss.

Monitoring alone is a means towards improved winter survival. The table below compares % individuals and % winter loss for individuals who monitored all colonies compared with those who monitored none. The nine-year difference is eight percentage point better survival monitoring all colonies. The loss rate of 16-26% who monitored some colonies was variable, averaging one percentage point higher than those monitoring all colonies.

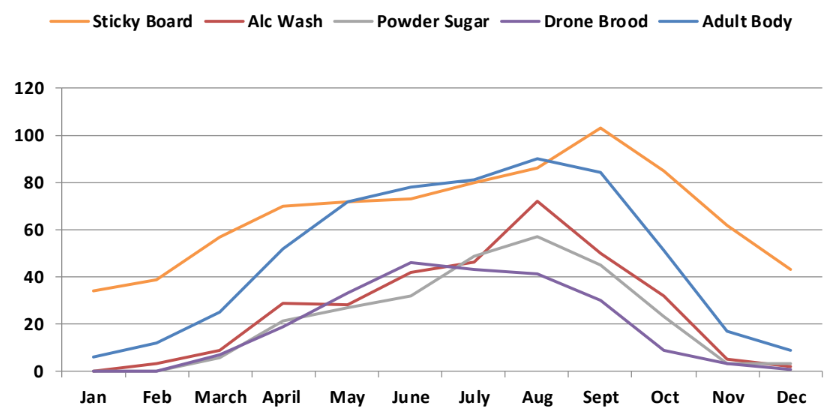

Individuals indicated use of 1.6 monitoring techniques on average. In total choices, in order of popularity of use, 85 individuals used alcohol wash (their loss level was 19%), 80 individuals used Sticky boards (22.5% loss level, 57 looked on adult bees for mites (loss level 32%), 51 looked on drone rood for mites (20% loss level) and 24 individuals used a sticky (debris) board to look for mites – they had 31% loss level. In the past 5 years, the use of sticky boards has decreased in use and alcohol wash has increased in use. This was the third year Alcohol use monitoring was the major monitoring technique and also with the lowest loss level. Figure 11 below Illustrates percent using the five monitoring methods.

Figure 11

Whatever technique used, most sampling to monitor mites was done in July – September, as might be expected since mite numbers change most quickly during these months and sampling results can be used to key control decisions. Figure 12 illustrates monthly sampling with five methods.

Figure 12

The most common sampling of respondents is both pre- and post-treatment (54% average). The sampling pre-treatment percentage has been decreasing while post treatment sampling has slowly been increasing. It is important to know if the treatment works so post treatment should not be avoided. Treatment without sampling was 13%, (same as last year). Figure 13.

Figure 13

It is important to KNOW mite numbers. Less effective mite monitoring methods include sticky (detritus) boards below the colony and powdered sugar. Often so much detritus drops onto a sticky board that counting the mites can be hard, especially for new beekeepers. Sticky boards used for a single day pre- and post-treatment can help confirm the effectiveness of a treatment, if numbers drop post treatment. Visual sampling is not accurate: most mites are not on the adult bees, but in the brood, especially when there is a lot of brood. Additionally, adult mites are NOT on the adult body where they can be observed (over 90% are on the lower abdomen, tucked within the overlapping bee sternites). Sampling for mites in drone brood needs to be refined as a predictive number; they can be used as an early warning ls cells had mites.

See Tools for Varroa Monitoring Guide www.honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroa on the Honey Bee Health Coalition website. The Tools guide suggested mite level to use to base control decisions based on the adult bee sampling. A colony is holding its own against mites if the mite sample is below 2%. It is critical to not allow mite levels to exceed 2-3% during the fall months when bees are rearing the fat fall bees that will overwinter. It is also the most challenging time to select a control method (if one is deemed needed) as potential treatment harm may negatively impact the colony. We see more colonies suddenly disappear (abscond?) during the fall, which may be related to the treatment itself.

Mite Control Treatments

The survey asked about non-chemical mite treatments and also about the use of chemicals for mite control. Twenty-nine individuals (15.5%) said they did not employ a non-chemical mite control and 6. Those 29 individuals who did not use a non-chemical treatment reported a 26% winter loss, a half percentage point higher than overall, while those 6 who did not use a chemical control lost 23% of their colonies, two and half percentage points lower than the overall average. The individual options chosen for non-chemical control and chemical are discussed below.

Non-Chemical Mite Control: Of nine non-chemical alternatives offered on the survey (+ other category,) 38 individuals (20.5%) used one method, 54 used two, 42 used three, 17 used 4, 7 used 5 and 4 individuals used 6 or 8. Individuals using a single method had 36% loss rate, those using two had a 22% loss rate, those with three similarly had a 22% loss, the 17 using 4 had loss level of 14%, the 7 using 5 had 9% loss and the 4 using the greatest number of options had a 30.5% loss. The individuals doing none (29 individuals) had 26% loss. Clearly using more than one method/tool (within a limit) improves success.

136 individuals (73% of total respondents – 6 percentage points higher than last year) listed use of screened bottom board. The next most common selection was distinctive colors (63 individuals= 34% of respondents). The use of the remaining selections is shown in Figure 15; number of individuals in ( ), the bar length represents the average loss level of those individuals using each method. Those left of green dashed line had improved survival.

Figure 15

Two of the non-chemical alternatives have demonstrated reduced losses over the past 7 years. Reducing drifting such as spreading colonies (28 % loss average for 6 years – question not asked in 2016-17 survey) and brood cycle break (31.3.% average) have consistently year after year demonstrated somewhat better survival than average loss (33 % average loss last 6 years and 35.4 % loss last 7 years respectively). Different colony colors in apiary )17%) and drone brood removal (20% loss) were helpful this year and barely better in 6-year loss average. Small cell/Natural comb and requeen, managements of only a few individuals showed better survival this year.

Chemical control: For mite chemical control, 6 individuals (3% of total respondents) used NO chemical treatment. They had a loss level of 23%. 30% (74 individuals) who used FAST TRACK and did not supply information had a loss level of 35.5%. Those using chemicals used at a rate of 0.94/individual down from 2.3/individual last year and the previous year when it was 3.3/individual. Eighty-four individuals using a chemical 48%) used one chemical. Overall, these individuals had a 29% loss level. Individuals who used 2 chemicals (70 individuals -40% of respondents had 17.5% loss. The three individuals that used 4 chemicals did even better – no loss of 13 total colonies. The individuals using 3 chemicals (18 individuals) had a 31% loss. The biggest use was oxalic acid – 145 individuals (83 of chemical users) – they had loss level of 21%. Figure 16 shows usage and loss levels.

Apivar: The number of times a chemical was used was captured in the survey. For example, there were 42 individuals who used Apivar, the synthetic miticide with amitraz. One used it once – 1 of 4 colonies did not survive=25% loss, 11 individuals used it twice and had 20% loss and the 30 individuals who used Apivar a single time had a 26% loss level. Overall, for the 42 Apivar users 24% loss. That is what is graphed in Figure 16.

Essential Oils: Apiguard, the essential oil gel, had a very decent survival level. It was used four times by one individual – 1 of 3 colonies survived for a 67% loss, the single individual who used it three times had all 4 colonies survive 0% loss, 17 individuals who used Apiguard twice had 14% loss and the 32 individuals using it once had 18% survival. Overall Apiguard users (51 individuals) had a 17% loss rate. There were 16 individuals who used APiLifeVar, also an essential oil miticide. The single individual who used it once lost all 3 colonies, 100% loss, whereas the one individual using it 3 times had all 3 colonies survive =0% loss. Two individuals using it twice had 0 loss (6 colonies total) and the 12individuals using APiLifeVar one time lost 16 of 66 fall colonies = 24% loss. Overall loss=24% for this miticide.

Formic Acid: Formic acid is a powerful acid capable of causing collateral damage to the bee brood and is sometimes a queen killer. Three individuals used it one and lost 3 of 5 colonies – 6% loss, ten individuals used it twice and lost 12 of 37 colonies – 32.5% loss and those using it once (11 individuals) lost half of their colonies – 50% loss. Overall, the 22 formic acid users did not do very well with mite control – they had a 43% loss.

Hopguard: this is another acid miticide. It too did not promote good survival. Two individuals using it 3 times didn’t lose any colonies (5 total); the 3 individuals using it twice lost 55.5% and the 6 individuals using it once lost 38.5%. Overall loss level was 38%.

Oxalic acid: the vast majority of individual treating for mites chemically used oxalic acid in one of three ways, as drizzle (OAD), and vaporization (sublimation) OAV and oxalic acid in absorbent pads meant to keep oxalic acid in the hive for an extended period OAE. There is a new approved product VarroxSan on the market, but it was not available for use until after this year, so users followed a recipe and made their own absorbent pads. Overall 145 users of oxalic acid had a 21% loss.

QAD: One individual drizzle 6+ tomes and lost 1 of 3 colonies 33% loss, 1 individual used it three times and lost both colonies overwinter – 100% loss, the three individuals who used it twice also had a 33% loss level while those using it once lost only 5 of 53 colonies for a 9.5% loss level – Overall 16 users had a 16.5% loss level.

OAE: This is a relatively “easy” way to use oxalic acid. Forty-six individuals used it to control mites and had only a 14% loss. Four individuals used it 6+ times and had a 14% loss, the 4 individuals using it 4 times did even better – they had a 6% loss. Five individuals used it 3 times with a 23% loss (3 of 13 colonies did not survive), six individuals used it twice with an 18% loss and those 27 individuals using OAV once had a 14% loss.

OAV: A total of 136 individuals used oxalic acid vaporization to control mites. They did this on 927 colonies, 71 survived for a 20% loss level. Twenty individuals used OAV 6+ times and had a 15.5% loss, sixteen individuals used it 5 times with a 30% loss and 19 individuals used it four times with a 31% loss. It is unclear why only 4 or 5 uses would not perform better. The 26 individuals using it 3 times had a 21.5% loss, the 25 individuals using it twice had a 13.5% loss and those 30 individuals using it a single time had a 24% loss.

Other chemicals used included mineral oil – the single user lost 2 of 8 colonies = 25% loss and use of oregano oil again a single user but in this instance all 3 colonies survived (0% loss) and finally the 3 powdered sugar users lost 1 of 8 colonies = 12.5% loss

Consistently, over the last 8 years, four different chemicals have helped beekeepers improve survival. These were essential oils Apiguard (average 8-year loss level 27.6%), Apivar (29.9% average 8-year loss level), ApiLifeVar (29% average loss level over last eight years) and Oxalic acid vaporization (also 29% average loss level over last 8 years). The average loss level has been 35.7% in the last 8 years. Formic acid too has done better than average in the last 7 years but the product has changed from MAGS to Formic Pro so I cannot be sure what Formic acid product was used by the 107 respondents who reported using it. Oxalic acid drizzle did well this year (16% loss level) – average for the last 8 years is 33.7%. The extended OAE (absorbing oxalic acid and glycerin into sponges) did very well in promoting better than average survival in the past two years and its use has increased dramatically. It was the best product for OR beekeepers this year – 46 users had a 14% loss, 11.5 improvement over average loss.

Figure 16

Antibiotic use

Five individuals (2.5%) used Fumagillin (for Nosema control) and had a 39% loss rate. One individual indicated use of Terramycin, they had 43% winter loss. Last year no Terramycin users were recorded.

Queens

We hear lots of issues related to queen “problems”. Queen events can be a significant factor contributing to a colony not performing as expected. Thirty-three percent elected to FAST Track and did not respond to this final set of questions. Eighty of the 168 respondents (47.5%) who responded to this question said they had marked queens. This is 7 ½ percentage points greater than last year. The related question then was ‘were your hives requeened in any form?”, to which 80 (115 individuals) said yes (16 percentage points higher than last year). When asked how colonies were requeened (multiple answers were possible) 54 said their colonies swarmed and 27 of their colonies superseded. Fifty colonies were split (and they raised an emergency queen presumably). A total of 64 said they introduced a mated queen, 9 introduced a virgin queen and 31 said they introduced a queen cell.

Closing comments

This survey was originally designed to ‘ground truth’ the larger, national Bee Informed loss survey. See statewide PNW reports for OR and WA for this comparison (graph 5 in this report). The numbers, while slightly different, do in fact track well. Unfortunately, the national BIP survey was discontinued after 2023. A new national survey administered by Apiary Inspectors of America, Auburn University and by Natalie Steinhauer, a research associate at Oregon State University has continued a national survey but response has not been as large. The BeeInformed survey measured larger scale OR beekeepers, not backyarders. Loss rates are of total colony number and more representative of commercial scale beekeeping. Reports for individual bee groups are customized and only available from the PNW website; they are posted for previous years.

I intend to continue to refine this instrument each season and hope you will join in response next April. If you would like a reminder when survey is open please email us at info@pnwhoneybeesurvey.com with “REMINDER” in the subject line. I have a blog on the pnwhoneybeesurvey.com and will respond to any questions or concerns you might have. Email me directly for quicker response. dmcaron@udel.edu Thank You to all who participated. If you find any of this information of value, please consider adding your voice to the survey in a subsequent season.

Dewey Caron May 2025

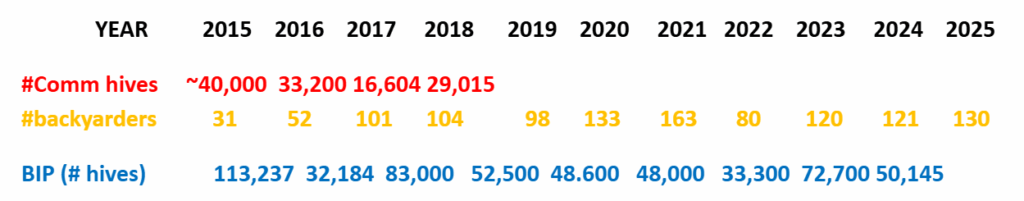

Winter Bee Losses of Washington Backyard Beekeepers for 2024-2025

by Dewey M. Caron

Click here to view a PDF of Washington report.

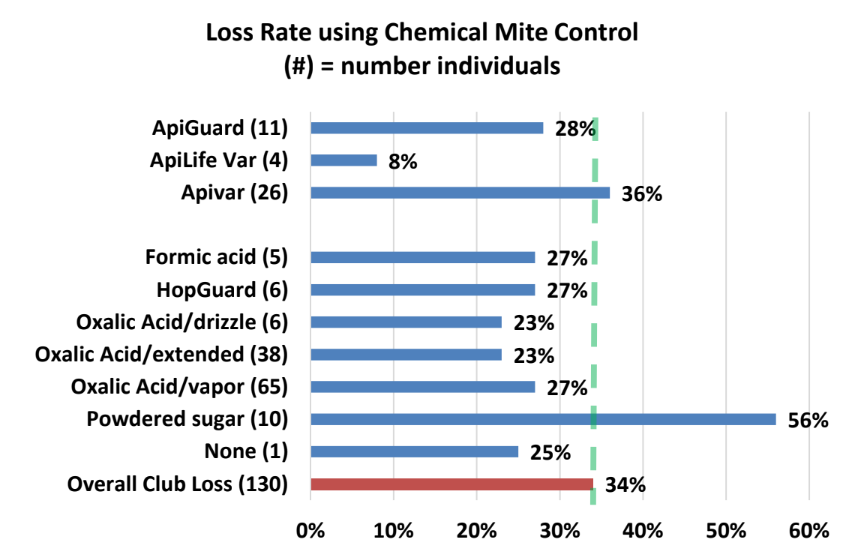

Overwintering losses of small-scale Washington backyard beekeepers = 34% an increase of three percentage points from last year, 11 percentage points below the 10-year loss average. One hundred and thirty Washington respondents, 9 more than last year. completed a survey and eleven above the 119.3 average respondent rate for the last six years. Individuals maintained up to 40 fall colonies. Information on winter losses and several managements related to bee health was included on the electronic honey bee survey instrument www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com.

Response by local Washington (WA) association members varied as indicated by numbers adjacent to club name. Losses of those club individuals are shown in blue bars in Figure 1. Statewide loss level was 34%. The survey included 676 fall Washington beekeeper colonies (17 fewer than last year).

2024-2025 Overwinter Losses by Hive Type

The Washington survey overwintering loss statistic was developed by subtracting the number of spring surviving colonies from fall colony numbers supplied by respondents by hive type. Results, shown in Figure 2 bar graph, illustrate overwintering losses of 130 total WA beekeeper respondents. Langstroth 8-frame beehives had lower average losses (28%) compared to Langstroth 10-frames hives (36%). Ten nucs of 30 in the fall failed to survive. Top Bar hive survival rate (35%, 11 of 17 in the fall) was similar to the Langstroth hives. There was single Warré hive and it survived. Of the 26 colonies listed under “other” hive type, 8 were IDed as AZ (only 3d survived), 5 as Apimaye (2 survived), the single long hive survived, one of two Slovanian hives survived, the single feral hive survived and of 9 “other’ not identified, 8 survived.

Figure 2

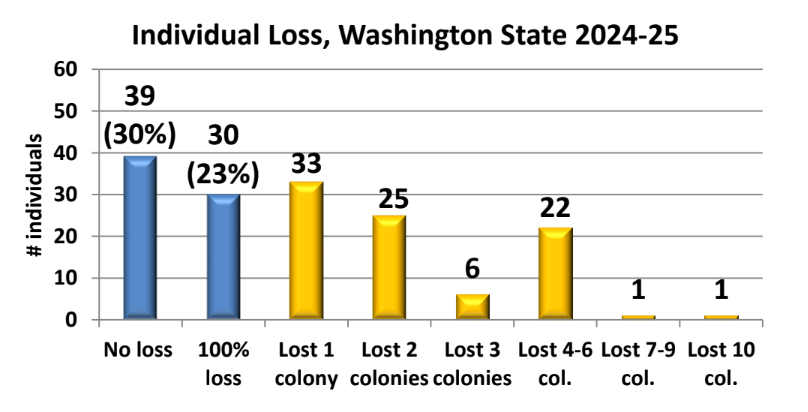

Thirty-nine individuals had no loss (124 colonies) while 30 beekeepers lost 100% (87 colonies). The greatest loss was one colony. The heaviest loss was 10 colonies. See Figure 3 graph.

Figure 3

The WA respondents to the electronic survey managed up to 40 fall colonies. Seventeen individuals had a single colony (and had colony loss of 47%), 29 respondents had two colonies (the greatest number) with 45% loss and thirteen individuals had three colonies (44% loss). Typical of previous surveys, fifty-nine individuals (45% of respondents) had 1, 2 or 3 fall colonies (loss level of 45%). Forty-two individuals had 4 to 6 fall colonies and had loss level of 48%. Four was the median number. Thirteen individuals had 7 to 9 colonies; they had a loss level of 21%. Ten individuals had 10-19 colonies with a loss level of 32%, 7 individuals had 20-40 colonies had a loss level of 18%. The 15 individuals with 10+ colonies lost 23%.

Forty-nine respondents (37.5% of total) had 1, 2 or 3 years of experience; they had a 37% loss level. The 8 individuals with one year of experience had the heaviest loss of 47%. Thirty individuals (23% of total respondents) had 4 – 6 years’ experience (medium number = 5 years’ experience) with a 32% loss, 21 individuals had 7-9 years’ experience (loss level 31%), 21 had 10-18 years keeping bees and 358% loss level and nine had 20+ years’ experience (4 individuals had 50 years’ experience, the maximum beekeeper experience years (these 4 had a 20% loss) and they had a 21.5% loss level. Examining the relationship of colony numbers and years’ experience related to loss shows that loss of colonies decreases by about 1/3rd with the greater number of colonies and/or years of experience.

Summary Statewide WA

1-3 colonies 45% loss 10+ colonies 23% loss

1-3 years’ experience 37% loss 10+ years’ experience 31.5% loss

One hundred six (81%) WA beekeepers had an experienced beekeeping mentor available as they were learning beekeeping. This percentage was six percentage points higher than last year, slightly higher than the 6-year average.

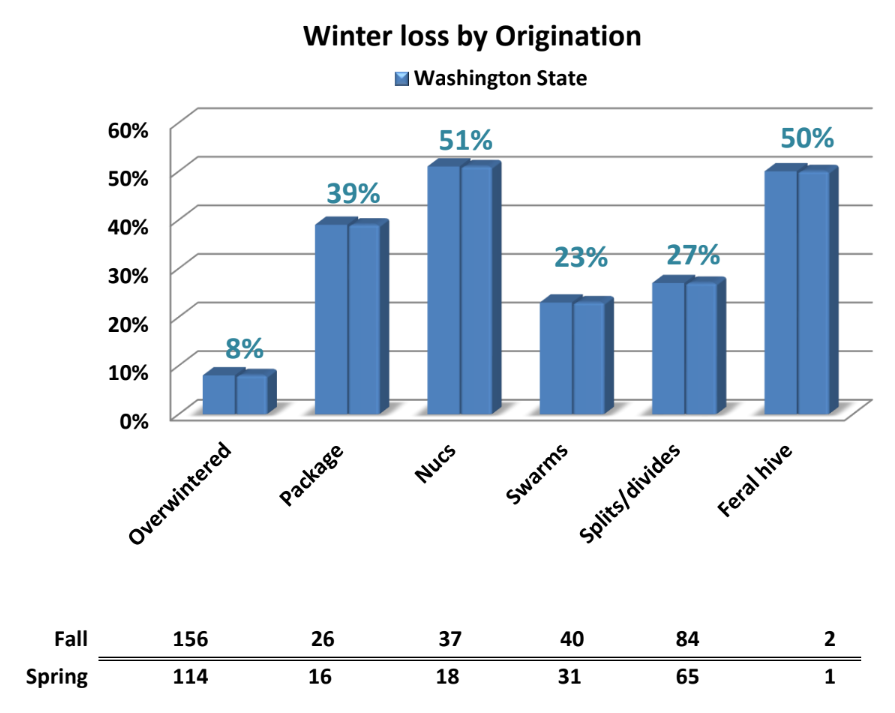

Survival Based on Hive Origination

We also asked about hive loss by origination. This year individuals could FAST TRACK the survey and bypass this question. Less than half of respondents, 62 individuals, did answer. Data shown in Figure 4 below. The best survival was previously overwintered, only 8% loss rate. Nuc-originated overwintered fared worse.

Figure 4

Comparison to Larger-Scale Beekeeper Losses

A different (paper) survey instrument was mailed to Pacific Northwest (PNW) semi-commercial (50-500 colonies) and commercial beekeepers (500+) from OSU asking about their overwintering losses. Response rate was reasonable until 2018 then the response became limited to only three individuals, and this was not considered representative of the larger scale beekeepers of Washington. Numbers are shown in red only for the 4 years 2015-2018 in Figure 5 below.

The BeeInformed.org (BIP) losses for Washington beekeepers for 2015 to 2023, the last year of the BIP survey, are representative of the larger scale beekeepers and are shown in blue in Figure 7 (ignore the 0 in 2024). Losses of backyard beekeepers from this survey are shown in orange line with black loss numbers. The response number was 130 for 2025. Average BIP loss (9 years) =27.9% and average WA backyarder loss (10 years) = 44.7%. In 2023 the larger-scale beekeeper loss exceeded losses of backyarders. The numbers included in the survey are shown below the figure.

In 2024 a new National survey was started by the group Apiary Inspectors of America, Auburn University and Oregon State University. Overwintering losses in this initial survey was 37.7. This is represented by an X in the chart. This survey was continued in 2024-25 season.

Figure 5

The reasons backyarders have had higher losses are several. Commercial and semi-commercial beekeepers examine colonies more frequently and they examine them first thing in the spring as they move virtually all their colonies to pollinate almonds in February. They also are more likely to take losses in the fall and are more pro-active in varroa mite control management.

The PNW survey was conducted in part to “ground truth” the annual BeeInformed Survey (BIP) also conducted during April. The BIP survey includes a mailed survey to larger-scale beekeepers and an electronic survey to which any Washington beekeeper can submit their data. Losses reported include colonies of migratory beekeepers who reported WA as one of their yearly locations. The BIP survey for the 2015-23 annual surveys reports receiving responses from 90 to 95% of respondents exclusive to Washington but they managed less than 5% of total colony count – thus, we can conclude the BIP tally is primarily of commercial beekeepers. They have large numbers of colonies in survey data, so the BIP losses reflect commercial losses not losses of backyarders. See https://research.beeinformed.org/loss-map/

Apiary sites and moves

Fifteen survey respondents had bees at more than a single apiary. Loss levels were similar or better at 9 of the original sites and better at 4 of the 2nd sites. Four had bees at a third site and losses were higher at one of the 3rd sites. Seven individuals moved bees. One moved for pollination, one moved for better site, one moved due to yellow jacket predation and the other four moved for reasons due to loss of site.

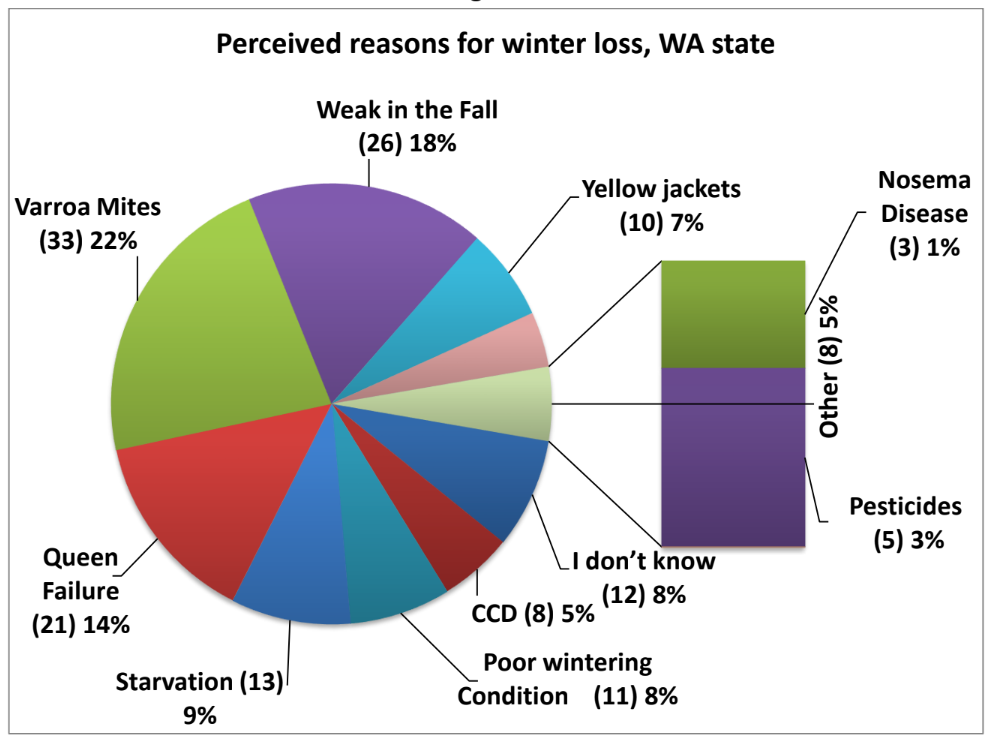

Colony death perceived reason and acceptable loss level

We asked survey takers who had winter losses for the “reason” for their losses. More than one selection could be chosen. In all there were 115 WA selections (1.85/individual) provided. Varroa mites (33 individuals, 22% of total selections) was the most common choice. Queen failure was 14%. Weak in the fall, starvation and poor wintering were also common choices, followed by yellow jackets and don’t know. The eight “other” listings were absconding, moisture, virus, EFB, late split and beekeeping error. Figure 6 below shows the number and percent of factor selections.

Figure 6

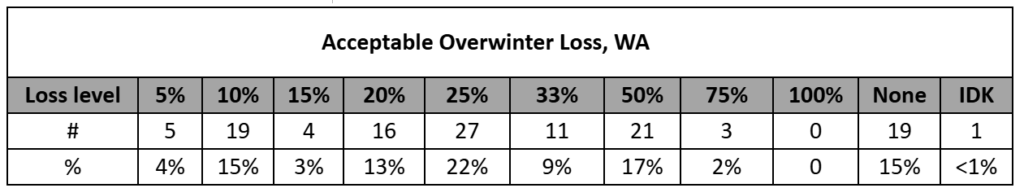

Acceptable loss: Survey respondents were asked the reason for loss. Nineteen (15%) indicated zero (no loss). Thirty-four percent of individuals indicated 10% or less. Twenty percent was medium choice. Nineteen percent said 50%+ was an acceptable loss level. See the table below.

Why do colonies die?

There is no straightforward way to verify reason(s) for colony loss. Colonies in the same apiary may die for several reasons. Examination of dead colonies is at best confusing and, although some options may be ruled out, we are often left with two or more possible reasons for losses. A dead colony necropsy can be of use. Opinions vary as to what might be an acceptable loss level. We are dealing with living animals which are constantly exposed to many different challenges, both in the natural environment and the beekeeper’s apiary. Individual choices varied from zero to 100%, with a medium of 20%.

Major factors in colony loss are thought to be mites and their enhancement of viruses especially DWV (deformed wing virus), VDV (Varroa destructor Virus (also termed DWV B) and Israeli and chronic paralysis virus. But we do not have a test for these viruses. It was interesting that queen problems were the most frequently indicated as were weak in the fall as leading reasons for loss.

Declining nutritional adequacy/forage and diseases, especially at certain apiary sites, are additional factors resulting in poor bee health. Yellow jacket predation is a constant danger to weaker fall colonies. Management, especially learning proper bee care in the first years of beekeeping, remains a factor in losses. What effects our changing environment such as global warming, contrails, electromagnetic forces, including human disruption of them, human alteration to the bee’s natural environment and other factors play in colony losses are not at all clear.

There is no simple answer to explain the levels of current losses nor is it possible to demonstrate that they are necessarily excessive for all the issues our honey bees face in the environment. It was encouraging to see from survey responses that losses this past year, 34% were still at a low level. More attention to colony strength and the possibility of mitigating winter starvation will help reduce some of the losses. Effectively controlling varroa mites will help reduce losses.

Colony Managements

Most Washington beekeepers do not perform just one management to their colony (ies) toward improving colony health and overwintering success. This analysis compares a single factor equated with loss level. Such an analysis is correlative and doing a similar management as fellow beekeepers does not necessarily mean you too will improve success. Individuals could FAST TRACK in their survey responses this year. For these first managements 91 individuals (70%) supplied management information.

FEEDING: Washington survey respondents checked 310 feeding options = 3.4/individual (last year it was 3.1/individual). Two individuals made no selections – they had 6 colonies and all survived. Seven respondents indicated a single choice but lost 25 of 36 colonies for 72% loss.

| # selections | # indiv (%) | % loss |

| 1 | 7 (8%) | 72% |

| 2 | 17 (19%) | 43.5% |

| 3 | 22 (25%) | 23% |

| 4 | 23 (26%) | 29.5% |

| 5 | 12(14%) | 26.5% |

| 6&7 | 6 (7%) | 26% |

The most favorable outcomes were 3, 4 or 5 feeding managements. The table illustrates the relationship of number of selections to percent making selection (median was 3) and percent loss of those individuals.

Figure 7

The choices, with number of individuals making that selection, is in ( ), bar length indicates loss level of individuals doing this management (Figure 7). Those bar lengths to left of 34% (green dashed line) had better survival while those to right had greater loss level.

Feeding sugar syrup (75 individuals) and pollen patties (59 individuals) were the most common feeding option of respondents. Syrup feeders had a loss rate similar to overall loss rate (35% while the pollen patty feeders with 27% loss rate had a 6-percentage point better survival. They had a 24% loss rate, 9 percentage points better than the overall average. The Dry sugar feeders (75 individuals) also had an advantage over overall loss rate with a 28% loss rate, due to hard sugar candy feeders (24% loss rate, 26 individuals) and the 34 fondant feeders with a 28% loss rate. The 3 who checked “other” practices, feeding hive alive, showed good survival, 7 of 41 colonies did not survive =17% loss and the one using microbials had a 25% loss.

For the last 6 years of survey losses statewide, individuals doing no feeding had poorer survival in 6 of the 7 years, but numbers of individuals/colonies involved were generally low – this year two individuals with 6 colonies had total survival. Individuals that fed sugar syrup had marginally lower loss level in four of seven years (but not this year). The 9 liquid honey feeders had the best survival with only a 17.5% loss rate.

Individuals feeding non–liquid sugar in the form of hard candy likewise had lower losses in 5 of 7 years; this year 10 percentage points better survival. One individual who fed corn syrup had only an 11% loss). For individuals feeding protein, protein patty users showed slightly better survival in 4 of 7 years (this year 9 percentage points poorer survival); dry pollen feeders had better survival in five of the past six years; this year also.

WINTERING PRACTICES: We received 262 responses (2.9/individual compared with 2.7/individual last year) reporting WA beekeeper wintering management practices (more than one option could be chosen). Two individuals indicated doing none of the several listed wintering practices; they lost 1 of 3 colonies for 33% loss. The 6 and 7 selections by 6 individuals also had a 33% loss rate. Information on selections and loss rate in table.

| # selections | # indiv (%) | % loss |

| 1 | 17 (19%) | 47% |

| 2 | 19 (21%) | 38% |

| 3 | 23 (26%) | 24% |

| 4 | 20 (22.5%) | 27.5% |

| 5 | 4 (4.5%) | 11% |

| 6 | 6 (7%) | 33% |

For those indicating some management, 17 did one single thing and had 47% loss level. The best survival was those with three, four and five selections. Information presented in table to right.

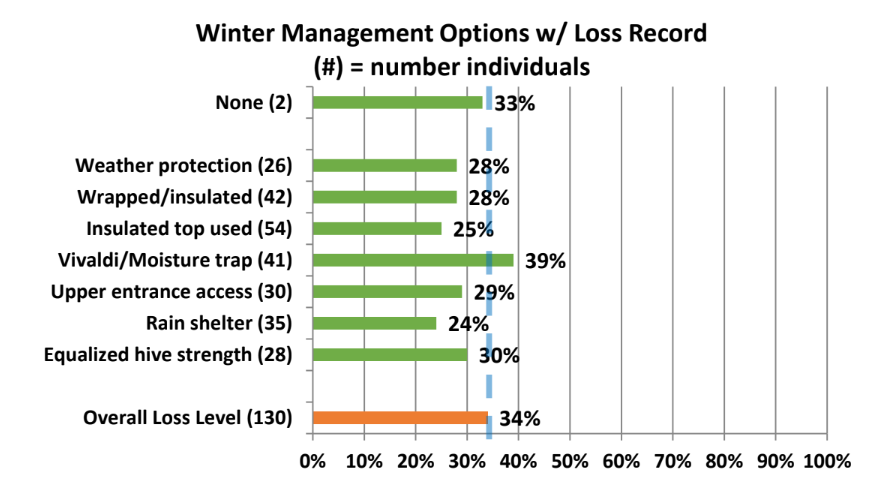

The managements selected that improved survival were rain shelter (35 individuals, 24% loss) and Insulated top (25 individuals, 25% loss). Figure 8 shows the number of individual choices and percentage of each selection. Bar length below 34% (blue dashed line) had better than average winter survival.

Over the past 6 years a couple of winterizing managements have shown improved survival. Those doing no winterizing had higher losses 6 of 7 years; this year 2 individual had a 33% loss but it was based on only 3 colonies. Equalizing hive strength in the fall demonstrated lower loss levels in all seven recent winter period (as in this one) and top insulation has demonstrated lower loss in five of seven winters – this winter a 9-percentage point advantage. Ventilation above the colony (Vivaldi Board/quilt box) demonstrated improved survival four of the seven winters, this year loss level was higher by 5 percentage points compared to overall loss. The 30% of individuals who did the FAST TRACK and did not indicate any managements had a 46% overwinter loss rate.

Figure 8

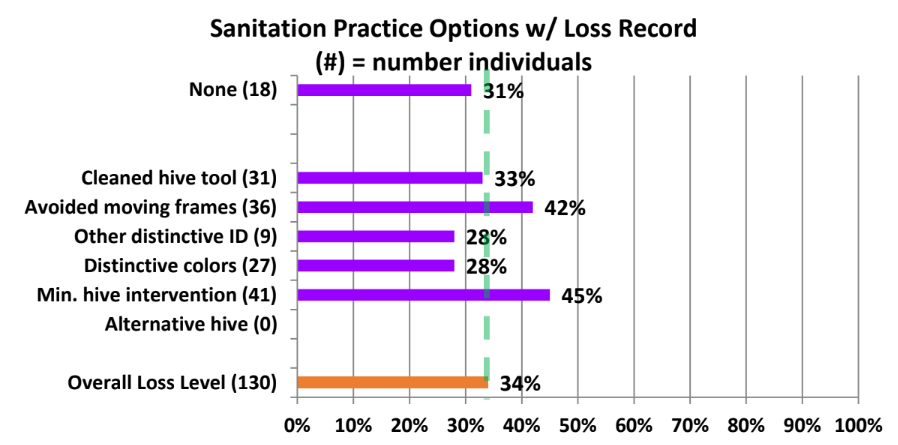

SANITATION PRACTICES: It is critical that we practice some basic bee sanitation (some prefer use of term bee biosecurity) in our bee care to help ensure healthy bees. We received 164 responses for this survey question 2.3/individual (last year it was 1.8/individual). Twenty-one individuals (29%) said they did not practice any of the six offered alternatives; they had a loss rate of 26%, 8 percentage points higher than the statewide average.

| # selections | # indiv (%) | % loss |

| 1 | 21 (29%) | 26% |

| 2 | 25 (34.5%) | 28.5% |

| 3 | 15 (21%) | 42.5% |

| 4 | 9 (12.5%) | 5% |

| 5&7 | 2 (3%) | 39% |

It is clear that none of the measures are robust enough to make a difference by itself in reducing winter loss. Figure 9 shows the number of individual choices and percentage of each selection. Bar length below 34% (green dashed line) had better than average winter survival.

In all six years doing none of these managements resulted in anything approaching better than average survival; this was the case this past winter when the 18 individuals doing nothing had average statewide losses. The managements of reducing colony drift, providing hives with distinctive color/distinctive hive ID measures are helpful managements but they do not measurably improve overwintering success.

Figure 9

SCREEN BOTTOM BOARDS (SBB)

Although many beekeepers use SBB to control varroa mites, BIP and PNW surveys clearly point out they are not or at best not a very effective varroa mite control tool. In this recent survey 17 Washington individuals (16%) said they did not use screen bottom boards; they lost 26.5% of their colonies. Those 21 beekeepers using SBB on some of their colonies lost 36% and the 53 individuals (%) using SBB on all of their colonies had 29.5% loss.

In eight survey years 19% of Washington beekeepers said they did not use SBB and 81% did use SBB on some or all of their colonies, see Figure 10.

Examining the seven-year average of SBB use, those using SBB on all or some of their colonies had a 40% loss level whereas for those not using SBB the loss rate was 40.9%, <1% positive survival gain for those using SBB versus those not using them). SBB are a very minor aid in improving overwinter survival for Washington beekeepers.

We asked if the SBB was left open (always response) or blocked during winter season. Fifty-four individuals (63.5%) said they always blocked SBB during winter. They had a 34% loss rate. Twenty individuals (13%) said they never blocked SBB and had a loss rate of 32%. Eleven individuals (8%) blocked them on some of their colonies. Their loss rate was 32%. So, the 65 individuals that blocked or sometimes blocked screen boards had 33% loss vs those who didn’t block had 30.5% loss. Over the past six years those closing have nearly an 8-percentage point advantage when the SBB is closed during the winter (although it was the opposite this season). There is no good science on whether open or closed bottoms make a difference overwinter, but some beekeepers “feel” bees do better with it closed overwinter. An open bottom, at least during the active brood rearing season, can assist the bees in keeping their hive cleaner and promote good hive ventilation.

Things that seem to improve winter success: It should be emphasized that these comparisons are correlations not causation. They are single comparisons of one item with loss numbers. Individual beekeepers do not do only one management option, nor do they necessarily do the same thing to all the colonies in their care. We do know moisture kills bees, so we recommend hives be located in the sun out of the wind. If exposed, providing some extra wind/weather protection might improve survival. Early spring pollen is important so locations where bees have access to anything that may be flowering on sunny winter days is also good management.

Feeding, a common management, appears to be of some help in reducing losses. Feeding hard sugar candy or fondant during the winter meant lower loss levels. Providing honey or sugar syrup, the most common selection, did not mean lower winter losses (liquid honey seemed better option) but these basic managements are useful in other ways such as for spring development and/or development of new/weaker colonies besides insuring better winter survival.

Feeding protein in any form does seem to slightly improve survival. The supplemental feeding of protein (pollen patties) might be of assistance earlier in the spring season has been demonstrated to help bees build strong colonies, but this may lead to greater swarming.

Winterizing measures that apparently helped lower losses for some beekeepers were top insulation and a rain shelter Spreading colonies out in the apiary and painting distinctive colors or doing other measures to reduce drifting also are of some value in reducing winter losses.

It is clear that doing nothing for feeding or winterizing resulted in the heaviest overwinter losses in the past but with few individuals and small colony numbers this was not indicted this year.

Replacing standard bottom boards for screened bottoms only marginally improved winter survival. It is apparently advantageous to close the bottom screens during winter.

Mite monitoring/sampling and control management

We asked the percentage of Washington hives monitored for mites during the 2023 year and/or overwinter 2023-24, whether sampling was pre- or post-treatment or both and, of the five possible mite sampling methods, what method was used and when it was employed. Seventy-one percent of Washington respondents provided a response and did not FAST TRACK for this section. Sixty individual respondents (65% – a decrease of 3 percentage points from last year) said they monitored all their hives. Losses of those individuals monitoring was 30.5%. Fourteen (15%) reported no monitoring; they had a higher loss rate of 23%. Eighteen individuals monitored some with a loss rate of 34%.

In order of popularity of use, 43 individuals used sticky boards, 63% total of 78 individuals who did some or all monitoring of colonies, same percentage as last year. Looking on adults was indicated by 38 individuals (49%) who did some or all colony monitoring followed by 36 individuals (46% of individuals doing monitoring, an increase of five percentage points from last year) that used alcohol wash. Twenty-eight individuals used drone brood monitoring and 10 used powder sugar to monitor. The sticky board users had 29% loss, alcohol washers had 26% and the 10 powder sugar users had 30% loss. Heavier losses were experienced by those looking on drones (35%) and on adults (45%).

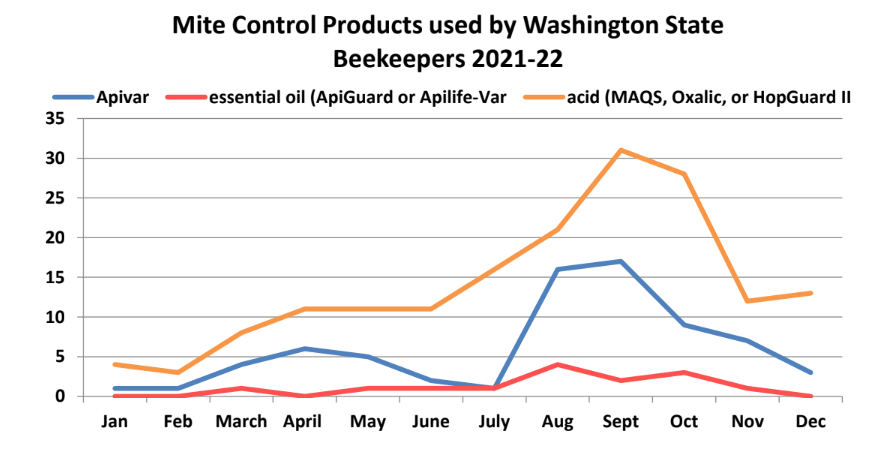

Most sampling to monitor mites was done in July – September, as might be expected since mite numbers change most quickly during these months and results of sampling can most readily be used for control decisions.

The most common sampling of respondents in 2024-25 was sampling both pre and post (27 individuals 40% of responses); they had 35% loss, just a single percentage point higher than overall lost rate for Washington beekeepers. Those 15 sampling pre had a more favorable loss rate (26%) while those 8 only sampling post treatment had a 43% loss. The 17 individuals who treated without sampling nor treating had 47.5% loss. The one individual that sampled but did not treat lost both their colonies.

It is important to KNOW mite numbers. Less effective mite monitoring methods include sticky (detritus) boards below the colony (often so much detritus drops onto a sticky board that picking out the mites can be hard, especially for new beekeepers) but sticky boards used for a day can help confirm the efficacy of a treatment when inserted post treatment. Visual sampling is not accurate: most mites are not on the adult bees, they are in the brood. Unfortunately looking for mites on drone brood is also not effective as a predictive number but can be used as an early warning that mites are present; if done, look at what percentage of drone cells had mites.

See Tools for Varroa Monitoring Guide www.honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroa on the Honey Bee Health Coalition website for a description of and to view videos demonstrating how best to do sugar shake or alcohol wash sampling. The Tools guide also includes suggested mite level to use to base control decisions based on the adult bee sampling. A colony is holding its own against mites if the mite sample is below 2%. It is critical not to allow mite levels to exceed 2% during the fall months when bees are rearing the fat fall bees that will overwinter. It is also the most difficult time to select a control method (if one is deemed needed) as potential treatment harm may negatively impact the colony. We are seeing more colonies suddenly disappear (abscond?) during the fall, which may be related to the treatment itself.

Mite Control Treatments

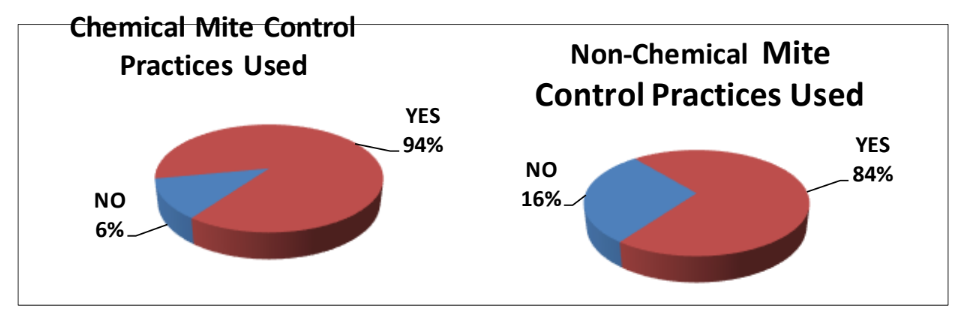

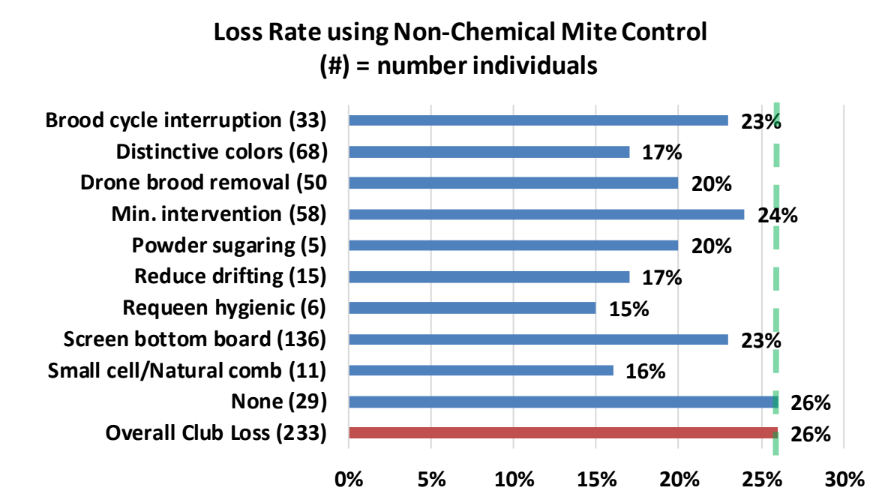

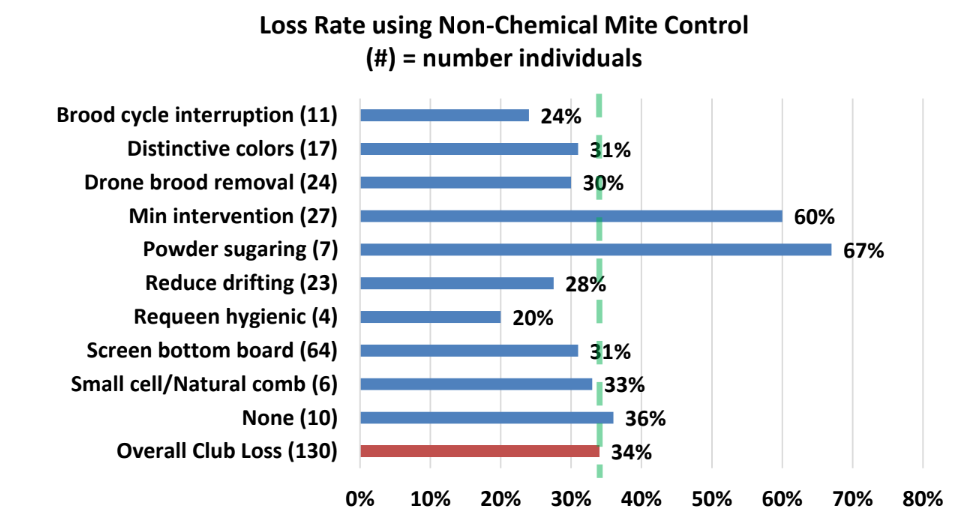

The survey asked about non-chemical mite treatments and also about the use of chemicals for mite control. A total of 97 answered this question with the remainder electing to FAST TRACK – those responding had 31.5% loss while those not providing management information had a 50% loss. Ten individuals (14%), eight fewer individuals than last year, said they did not employ a non-chemical mite control and a single individual (1%) did not use a chemical control. Those 10 individuals who did not use a non-chemical treatment reported a 36% winter loss, while those two who did not use a chemical control lost one of 4 colonies. The 33 individuals not providing information had a 45% loss level. The individual options chosen for non-chemical and chemical control are discussed below.

Non-Chemical Mite Control: Of nine non-chemical alternatives offered on the survey (+ other category), 185 selections were indicated 1.9/person (last year 2.2/individual). Twenty-eight individuals used one method and had a 36% loss, thirty-two used two (32% loss level), nineteen used three (30% loss) and 9 used four (34.5% loss).

Use of screened bottom board was listed by 64 individuals (79% of individuals selecting other than none). They had a 33% loss level. The best survival choices were requeening with hygienic stock by 4 individuals (20% loss) and brood cycle interruption (11 individuals had a 24% loss). The use of the remaining seven selections are shown in Figure 11; number of individuals in ( ), bar length represents average loss level of those individuals using each method. Those to left of the green dashed line had better than average survival.

Two of the non-chemical alternatives – drone brood removal (24 individuals, 30% loss) and brood cycle interruptions (11 individuals, 24% loss) have also been the most useful in previous year surveys in reducing winter losses in some of past 7 years but not all. Painting hives with distinctive colors has resulted in better survival in each of the past four of the past five survey years, as it did this year (31%). Minimum intervention (60% loss) and powder sugaring (67 percent loss by 7 individuals with 18 hives) showed the worst survival.

Figure 11

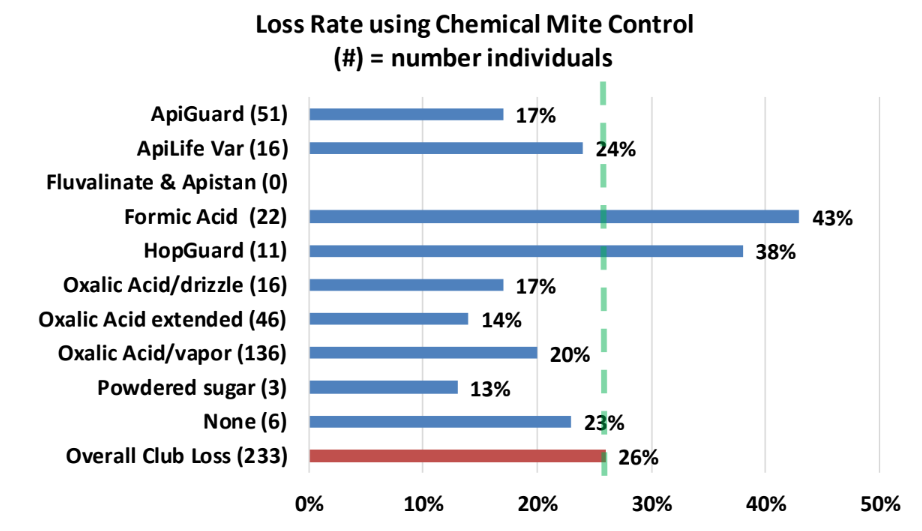

Chemical Control: For mite chemical control, one individual (1% of total respondents) used NO chemical treatment; this individual had a 25% loss level (the last three years those doing no treatments lost 100%, 61% and 67% but colony number lost (average 8) was not extensive). Those using chemicals used at rate of 1.6 /individual (last year 2.1/individual). Fifty-four individuals (58%) used one chemical and had 37% loss, 31 used two and had 24% loss, 4 used 3 (10% loss), 2 used 5 22% loss and one individual used 10 (lost 2 colonies of 9 and had a 22% loss level). Figure 12 illustrates the number of uses ( ) and bar length indicates the loss rate for those using that chemical.

Apivar: One-time users (14 individuals) had a loss rate of 41.5%, while 7 individuals using it twice the loss rate dropped to 38.5%. Five individuals used it more than twice. For example, the 2 individuals who used it 3 times didn’t lose any of their 5 colonies, but the 2 individuals who used it 4 times lost 5 of 8 colonies (=62.5% loss) and the one individual who used it 5 times experienced a 13% loss. The 26 users of Apivar had a 36% loss.

Apiguard: The 13 individuals that used it once had 34% loss, the 4 individuals who used it twice had a 10-percentage point improvement – only a 24% loss. Two individuals used it twice and lost 2 of 4 colonies (50% loss), the two who used it4 times had even poorer survival they lost 9 of 10 colonies (90% loss). Two individuals said they used it 6+ times and lost 3 of 35 colonies – an 8.5% loss rate. The overall loss rate for users of Apiguard illustrated that it is helpful for survival – overall 28% loss rate., a 6-percentage point improvement to overall loss of Washington beekeepers of 34%.

Figure 12

ApiLifeVar: Although there were only 4 individuals who used the essential oil material ApiLifeVar (one individual used it 3 times and the other 3 used it once – I am not sure that the individual indicating use 3 times was not actual use of 3 strips one week apart?) their survival rate was outstanding. The 4 had a loss of only 2 of 26 colonies – an 8% loss rate. Other herbals used had loss of 5 colonies for a 17% loss.

Hopguard: Six individuals used Hopguard, an acid. On used it once, 2 used it twice and 1 used it 4 and another 5 times. Overall loss rate 27%.

One individual used 10 different materials. This individual had 9 fall colonies and lost 2 for loss rate of 22%. Materials used included Fluvalinate, Coumaphos, Mita-a-thol and with another individual Mineral oil. Also used was powdered sugar, with 8 additional users – they had 44% loss level.

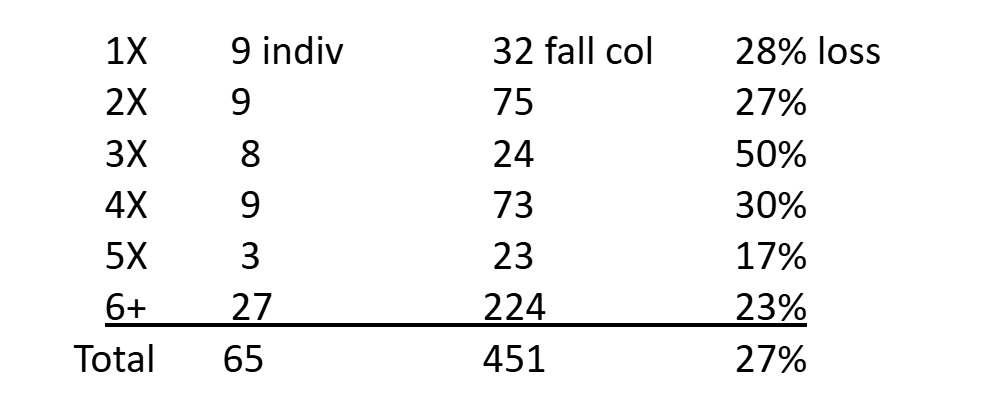

Oxalic acid. Oxalic acid is being extensively used, and it is proving to be effective in reducing overwintering loss. It can be mixed into sugar syrup and applied as a dribble between frames (often during winter). For convenience it is simply termed OAD. It can be absorbed into a pad and used between brood boxes, even when supes are in place (OAE) and finally it may be cooked with a vaporizer and used as gas – OAV. And it may be used many times. All three variations were used 6+ times by individuals for a total of 35 times.

OAD: Six individuals used OAD. One used it 6+ times not loss of 4 colonies, another used it 3 times and didn’t lose 2 colonies, 2 used it twice for 33% loss and 2 used it once and had a 28.5% loss. Overall loss rate= 23% for OAD.

OAE: Use of Oxalic acid in an extended manner has increased dramatically. Absorbent pads may last 4-8 weeks and then be replaced. Seven users of OAE indicated use 6+ times and lost only 7 of 60 so treated colonies for loss rate of 11.5%. One individual used it 5 times and had a 40% loss, 2 individuals used it 4 times and had a 43% loss. The 6 individuals using it 3 times fared better – they had a 26% loss, the 11 individuals using it twice did just as well with 27% loss rate and finally, individuals using it just once (11 individuals had a loss of 25.5%. The overall loss rate for OAE was 23%.

OAV: This chemical mite treatment was by far the most popular. Although it had the poorest survival rate for methods of oxalic acid use, a 27% loss rate, this was still 6 percentage points better survival than overall. Sixty-five individuals said they used OAV. The number of individuals, their fall colony number and loss is shown is table below.

Consistently, the last seven years five different chemicals have helped beekeepers realize better survival. The essential oils Apiguard and ApiLifeVar have consistently demonstrated the lowest loss level; this year 28% and 8% loss. Apivar, the synthetic (amitraz), has demonstrated better survival over the past 7 years but this year the 36% loss rate was 2 percentage points over the overall state loss rate.

Oxalic acid vaporization over the past 5 years has a 15.3% better survival (the survey did not differentiate Oxalic vaporization from drizzle prior before); this year a 6-percentage point better survival difference. Formic acid also normally provides better survival – this year a 6-percentage point better survival although use has declined.

The monthly use of Apivar (blue line), essential oil (red line) or an acid (green line) is shown in Figure 13 for winter of 2021-22. Further review is needed to determine if the timing of treatments was more effective than at other times for the various chemicals.

Antibiotic use

Four individuals, all with larger colony numbers (81 fall colonies), reported using Terramycin; the loss level was 23.5%. One individual indicated use of Tylosin – they had an 18.5% loss. Five individuals indicated the use of Fumagillin (Fumidil-B) for Nosema control; their loss rate was 34% (70 fall colonies). The single Nosevet user lost all 4 of managed colonies.

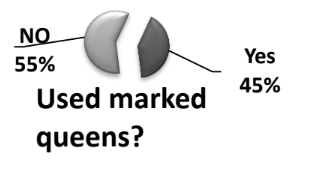

Queens

We hear lots of issues related to queen “problems.” Twenty-one individuals indicated queen problems as reason for loss in earlier part of survey (Figure 6). Queen events can be a significant factor contributing to a colony not performing as expected. We asked if you had marked queens in your hives. Fifty individuals (57.5%) said yes. The related question then was ‘were your hives requeened in any form?’ to which 54% (60 individuals) said yes; equal numbers said no (23%) or ‘not that that I am aware of.’ Loss level of yes was 33%, of the no 32% and ‘not aware of’ was 30%.

One technique to reduce mite buildup in a colony is to requeen/break the brood cycle. The question “How did bees/you requeen“ received 120 responses, 2/individual (more than one option could be checked). Thirty-three individuals indicated they requeened with a mated queen and they had a 33% loss level, five used a virgin queen (45% loss) and 13 used a queen cell (30% loss). Thirty-one said they split their hive(s) 26% loss, 18 indicated their colonies swarmed 20% loss and 22 said supersedure occurred – they had a 26% loss. Loss levels of colonies that did it themselves via supersedure and swarming (40 instances) were more favorable (23%) compared to those whose queen replacement was managed by the beekeeper via queen or queen cell (51 instances, 33% loss). Splitting colonies (31 instances) had a 26% loss rate.

Closing comments

This survey was originally designed to ‘ground truth’ the larger, national Bee Informed loss survey. The numbers while slightly different do in fact track well. Unfortunately, my commercial survey response decreased and in 2023 the national BIP survey was discontinued. The BeeInformed survey measures the larger scale WA beekeepers not the backyarders as loss rates are of total colony number. I have discontinued recording WA commercial/ sideliner numbers as I receive too few responses to be representative of them. Reports for individual bee groups are customized and only available from the PNW website; they are posted for previous years.

I intend to continue to refine this instrument each season and hope you will join in response next April. If you would like a reminder when the survey is open please email us at info@pnwhoneybeesurvey.com with “REMINDER” in the subject line. I have a blog on the pnwhoneybeesurvey.com and will respond to any questions or concerns you might have. Email me directly for quicker response. dmcaron@udel.edu

Thank You to all who participated. If you find any of this information of value, please consider adding your voice to the survey in a subsequent season.

Dewey Caron May 2025