** Looking for a report in your specific region? Refer to the Individual Club Reports page.

** Scroll down to see the Washington Backyard Beekeepers Winter Bee Loss Report, 2018-19 or click here to view Washington as PDF.

Winter Bee Losses of Oregon Backyard Beekeepers, 2018-2019

Dewey M. Caron and Jenai Fitzpatrick

Click here to view a PDF of Oregon report.

Overwintering losses of small scale Oregon backyard beekeepers were once again very extensive this past winter. The reason(s) for colony losses are not always obvious as there often are several contributing factors. Herein we review and discuss the data provided by 416 OR smaller-scale beekeepers, 112 more respondents than last year. Results of the 98 Washington survey respondents is included in a different document as are club reports for which 20 or more returns were received.

This report presents the results of a 10th season of loss surveys of small-scale Oregon (hobbyist/backyard) beekeepers and the 5th season of the expanded digital version. This annual survey is conducted electronically at www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com during April and supplemented with paper surveys distributed at several late-March and April local association meetings.

Characterization of survey respondents

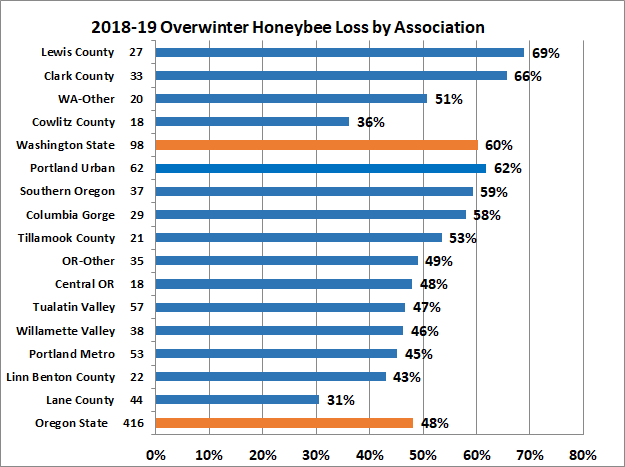

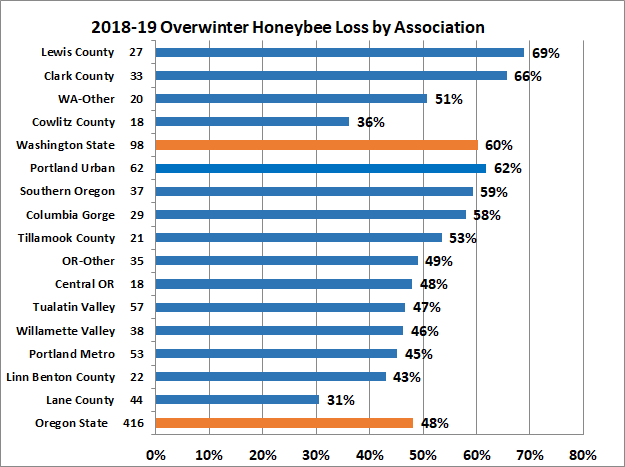

Surveys were received from members of 16 local Oregon (OR) associations and 7 Washington associations. The majority of the respondents (72%) keep bees in the I-5 corridor, Eugene, OR to Tacoma WA. Figure 1 shows number of responses and club loss rate for Oregon/Washington clubs providing 18 or more returns.

OR-other includes 11 Columbia County, 10 Central Coastal, 7 Douglas County, 4 South Coast, 2 Coos County and a single return from Klamath County. Colony numbers ranged from 1 to high of 38 colonies (40 was highest number In Washington). Washington other identified in Washington State report.

Seventy one per cent (71%) of OR beekeepers indicated they had a mentor available for the first years of beekeeping. This is encouraging as the learning curve is a steep one for new beekeepers and mentors can significantly help new individuals get through the critical 1st / early years keeping bees.

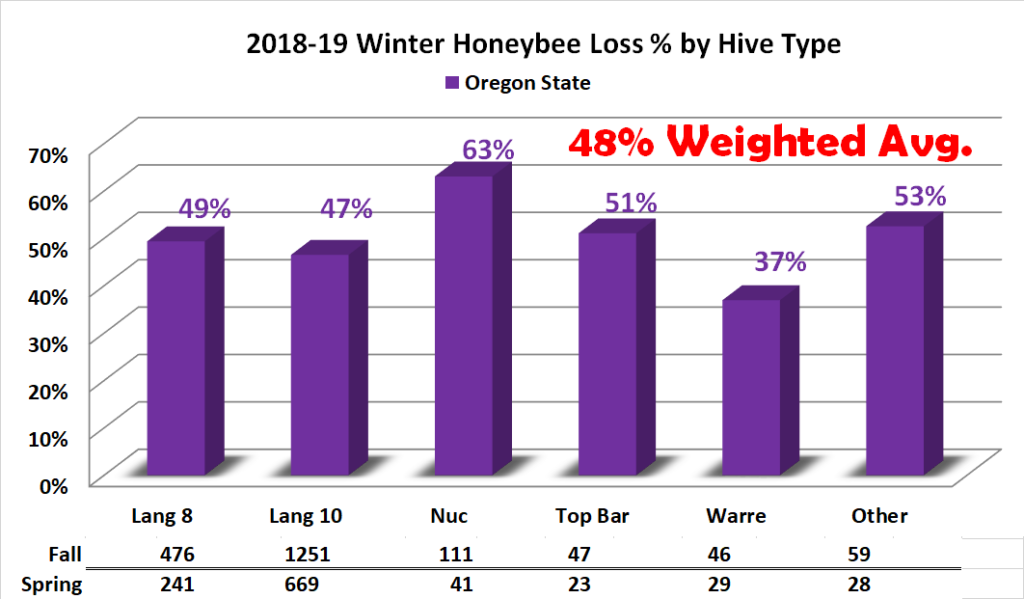

2018-2019 Overwinter losses (based on hive type)

Total OR backyard beekeeper overwinter loss = 48%.

The loss statistic was developed by asking number of fall colonies and surviving number in the spring by hive type. Results are shown in bar graph of Figure 2. Respondents had 1987 fall colonies; 1031 colonies survived to spring. Eighty-seven percent (87%) of hives were 8 and 10 frame Langstroth hives. Of 59 other hives indicated on responses, 26 were long hives and 4 additional hives were special nucs. 22 other were not identified (although this information was requested). A total of 22 other hives might be a non-movable frame hive, thus, at most 6% of hives were non-traditional hives. Ninety individuals (21.5%) kept more than one hive type.

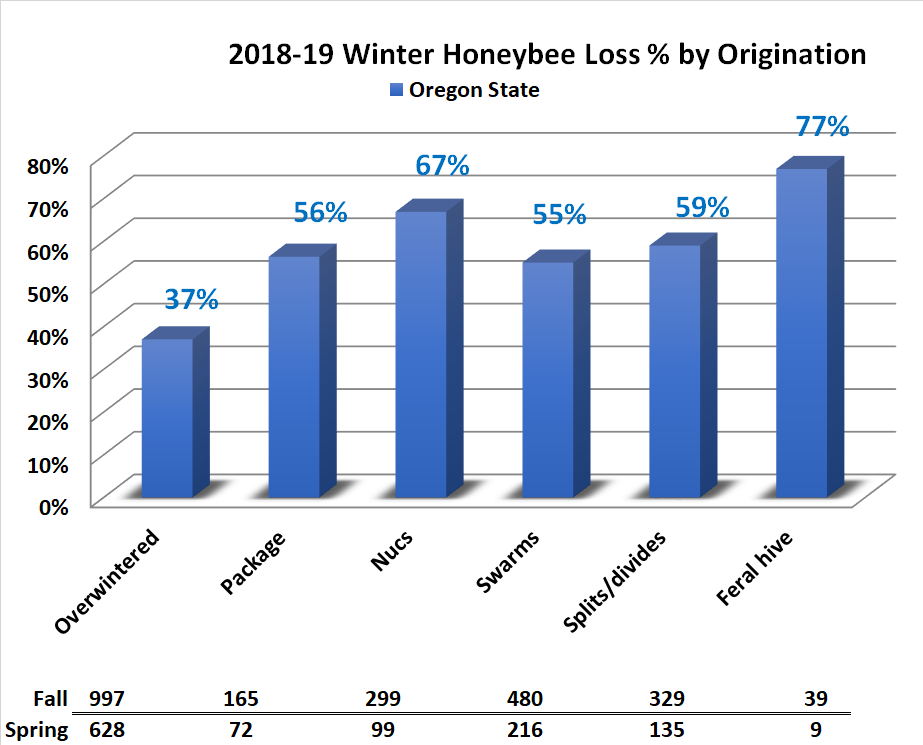

Survival based on hive origination

We also asked survey respondents to characterize their loss by hive origination. The result is graphically presented below in Figure 3. There was relatively little difference but as expected overwintered colonies had the best survival (37% loss) and nucs and feral hive transfer did less well. Overall losses of packages, swarms and splits were similar, 56-59%.

The winter losses of PNW 8-frame Langstroth hives was similar to the loss rate of 10-frame Langstroth hives. There has been no statistical difference in 4 of 5 years in loss percentage between 8 and 10 frame hives. Nuc losses are typically higher (4 of 5 years). Top Bar, Warré and other hive losses (excluding the long hives and nucs) have experienced slightly higher loss of 51% compared to movable frame hives

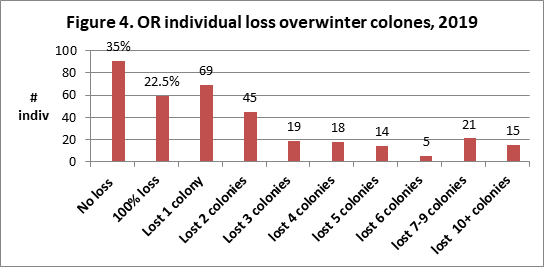

Thirty-five percent (35%) of OR respondents (91 individuals) had NO LOSS overwinter, whereas 22.5% (59 individuals) lost 100% of fall colonies. Sixty nine individuals lost 1 colony, 45 individuals lost two colonies, 19 respondents lost 3 colonies and 18 lost 4 colonies. Fourteen individuals lost 6 to 9 colonies and 15 individuals lost 10 or more colonies – highest loss was 18 colonies. Numbers are reflective of the fact that backyarders keep on average 3 colonies.

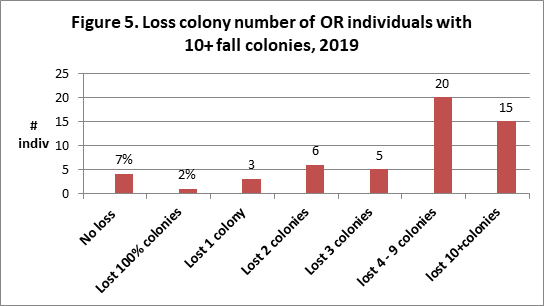

Losses of individuals who managed 10+ colonies

Eighty seven per cent of OR beekeepers had 1 to 9 colonies. There were 54 beekeepers (13%) who had more than 10+ fall colonies. Collectively they had a 41.7% loss, 6 percentage points lower than individuals that had 1 to 9 colonies in the fall. Four of these 54 individuals (7%) lost no colonies, while 1 lost all their colonies. Thirteen (24%) lost 1, 2 or 3 colonies. The 54 individuals with 10+ colonies tended to have more beekeeping experience. Four had 3 years’ experience, 20 had 4-9 years, and 15 had 10+ years experience.

Comparison to larger-scale beekeeper losses

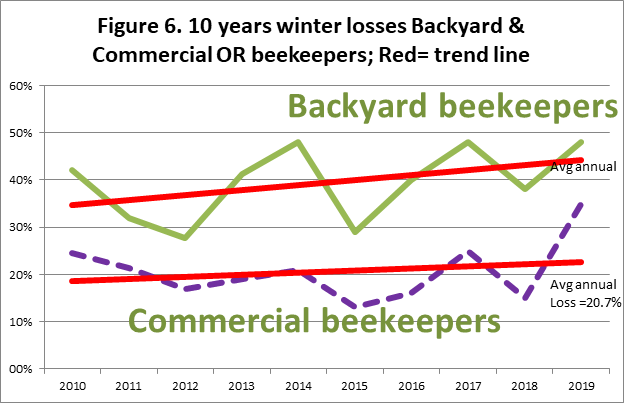

A different (paper) survey instrument was mailed to Pacific Northwest (PNW) semi-commercial (50-500 colonies) and commercial beekeepers (500+) asking about their overwintering losses. Six Oregon commercial and six semi-commercial beekeepers (22,900 colonies, approximately 31% of the estimated total number of colonies in the state) reported overwinter losses of 37%. Small scale (backyard) beekeeper losses have range from fifteen to 20 percentage points greater compared to losses of commercial/semi-commercial beekeepers over the last 10 years as shown in Figure 6. Incidentally, the national losses for those respondents from OR with the BeeInformed survey essentially mirrors losses of the larger scale losses even though both larger and smaller scale individuals are tallied. Red line is loss trend.

Loss rates at different locations

We asked loss related to location of the hive. Fifty three individuals had more than a single location. Loss rate at these out apiaries was one percentage point lower than the overall loss rate of 48%. Information supplied on location will be used to develop location density maps, similar to maps prepared by Jenai in 2014.

Overwinter losses of members of different organizations are shown in the Figure 1 above. The loss rates varied from a low of 31% for the Lane County beekeeper respondents to a high of 62% in PUB Association. The 2X range of losses, was also seen in 2017 spring. Last year it was a 3X difference and in 2016 a 4X difference, range of 20% to 80%.

Who are Survey respondents?

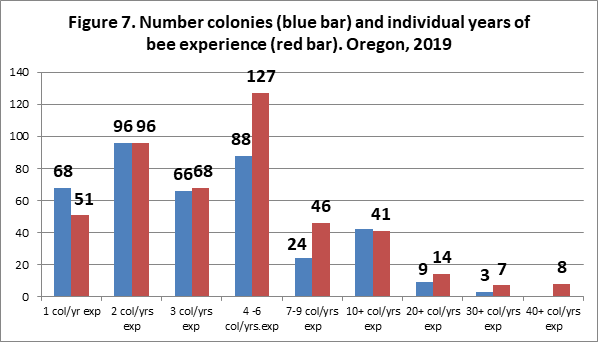

To better characterize the survey population, we tallied number of fall colonies for the 416 respondents. Sixty-eight individuals had 1 colony, 105 had 2 colonies (the most common colony number) and 66 individuals had 3 colonies (the middle number). Number of individuals with 4-6, 7-9 and 10+ colonies (15% of individuals) shown in Figure 7 blue bars. Highest colony number was 38.

We also asked how many years of beekeeping experience survey respondents had. The medium years of beekeeping experience for Oregon beekeepers was 3 years. 52% of respondents indicated 1, 2 or 3 years of experience, 127 individuals (30.5%) had 4, 5 or 6 years’ experience and 11% had 7, 8 or 9 years experience. On other end of spectrum, 70 individuals (17%) had 10+ years experience. 50 years experience was the highest. Figure 7 red bars.

Twenty five individuals (6%) moved colonies during the year. Reasons listed for move included 2 individuals moving hives a few yards to several feet to improve hive siting, 6 individuals who moved for better forage conditions/better site, 1 moved nucs to different site, 2 moved to give hives to friend/family, 8 moved bees for pollination, 2 moved from bear predation, another to escape wildfire and 2 to reduce yellow jacket predation.

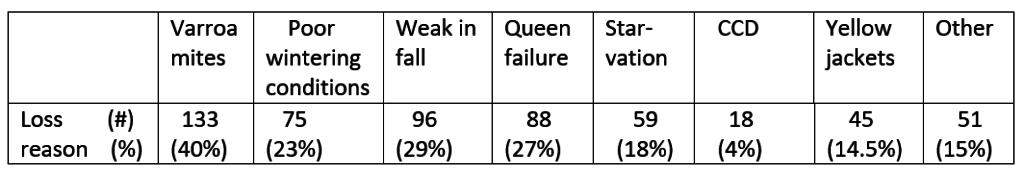

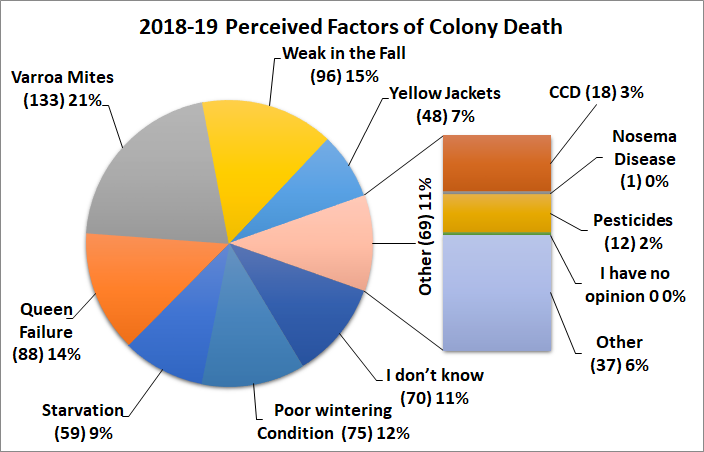

Colony Death perceived reason and acceptable level

We asked individuals that had colony loss (91 individuals had no loss) to estimate what the reason might have been for their loss (multiple responses were permitted). There were 726 total listings, 2.35/individual. Varroa (40% of respondent choices, 21% of total responses), followed by weak in fall (29% of respondents, 15% of total responses) and queen failure (27% of respondents, 14% of total responses) were most commonly checked. 70 individuals chose Don’t know. Among other, 12 individuals listed pesticides. NOTE: Table % is respondent choice; Figure 8 % is total responses.

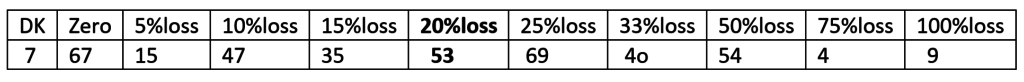

Acceptable loss: Survey respondents were asked reason for loss. Sixty seven (17%) indicated zero (no loss). Forty two percent of individuals indicated 15% or less. 20% was medium choice. Seventeen percent said 50% of greater was an acceptable loss level. See table below.

Why colonies die?

There is no easy way to verify reason(s) for colony loss. Colonies in the same apiary may die for different reasons. Examination of dead colonies is, at best confusing, and, although some options may be ruled out, we are often left with two or more possible reasons for losses. I am working on a book chapter on necropsy of dead bees and will post a colony necropsy report on the www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com website later this year.

Opinions vary as to what might be an acceptable loss level. We are dealing with living animals which are constantly exposed to many different challenges, both in the natural environment and the beekeeper’s apiary. Individual choices varied from zero to 100%, with medium of 20%. This acceptable loss level has crept upwards over time.

Major factors in colony loss are thought to be mites and their enhancement of viruses especially DWV (deformed wing virus) and declining nutritional adequacy/forage and diseases. Pesticide in the agricultural environment weakens colonies. Yellow jacket predation is a constant danger to weaker fall colonies, Management, especially learning proper bee care in the first years of beekeeping, remains a factor in losses. What effects our changing environment such as global warming, contrails, electromagnetic forces, including human disruption of it, human alteration to the bee’s natural environment and other factors, play in colony losses are not at all clear.

There is no simple answer to explain the levels of current losses nor is it possible to demonstrate that they are necessarily excessive for all the issues facing honey bees in the ours and their environment. Varroa mites and the viruses they transmit are considered a major factor, but by no means the only reason, colonies are not as healthy as they should be. More attention to colony strength and possibility of mitigating winter starvation will help reduce some of the losses. Effectively controlling varroa mites will help reduce losses.

Colony Managements

We asked in the survey for information about some managements practiced by respondents. Multiple responses were accepted. The survey inquired about feeding practices, wintering preparations, sanitation measures utilized, screen bottom board usage, mite monitoring, both non-chemical and chemical mite control techniques and queens. Respondents could select options and there was always a none and other selection possible. This analysis seeks to compare responses of this past season to previous survey years.

Most Oregon beekeepers do not perform just one management to their colony (ies) toward improving colony health and overwintering success. This analysis however is mainly of a single factor equated with loss level. Such analysis is correlative and doing a similar management as fellow beekeepers does not necessarily mean you too will improve success.

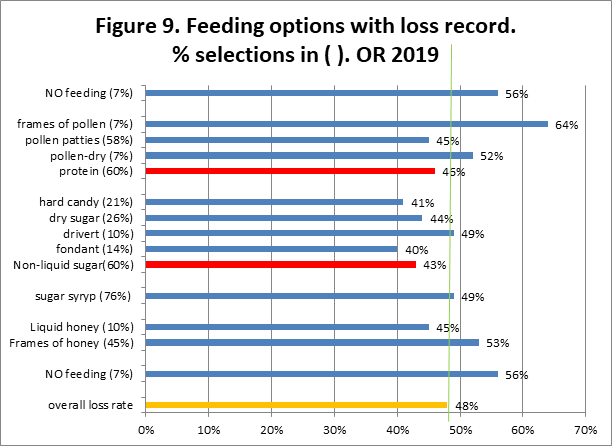

FEEDING: Oregon survey respondents checked 1165 feeding options = 2.8/individual. Seventeen individuals, other than those indicated no feeding (4%), selected a single choice, 108 (26% of respondents) indicated 2 choices (the greatest number) while 46 individuals (11%) had 5, 6 , and in one instance, 7 selections for feeding management.

The choices, with percent of individuals making that selection is in ( ); bar length indicates loss level of individuals doing this management. Figure 9. Those bar lengths to left of 48% green marker had better survival while those to right had greater loss level.

Twenty nine individuals (increase of 4 individuals over previous year) said they did NO FEEDING. They had 66 fall colonies and realized a 56% loss, 8 percentage points higher than overall loss level. For individuals indicating one or more feeding managements, feeding sugar syrup was the most common feeding option of respondents (315 individuals, 76% of respondents). Their loss rate was 49%, same as overall average. Percent of individuals feeding protein and non-liquid sugar was 60% (both 250 individuals); both collectively had better survival rate, although some selections, most notably frames of pollen and dry pollen and divert feeding, had heavier losses than the average overall loss rate.

For the last 3 years of heavier losses (48% in 2017 and 2019 and 38% in 2018 spring) individuals doing no feeding had poorer survival all 3 years. Individuals that fed sugar syrup had a 10% lower loss level (average for the 3 years). Those feeding honey (as frames or liquid) had lower loss only during the 2017-18 overwinter period. Individuals feeding non–liquid sugar (in any of the forms) had lower losses all three past winter seasons, with 5 or 6 percentage point improvement from overall losses. Dry sugar, hard candy feeders had improved survival all 3 winters while fondant feeders had better survival 2 of the 3 winters.

For individuals feeding protein, only the protein patty users showed better survival all 3 years; dry pollen feeders had better survival in one of the three years with losses the remaining two were close to the overall average.

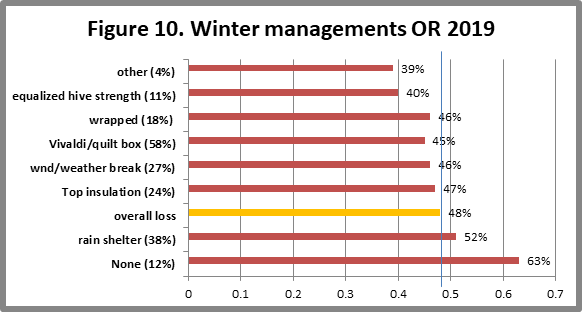

WINTERING PRACTICES: We received 939 responses (2.3/individual) about OR beekeeper wintering management practices (more than one option could be chosen). Fifty one individuals (12%) percent of the respondents indicated none of the several listed wintering practices was done; these individuals had a 63% winter loss, 15 percentage points higher loss than overall loss of 48%. For those indicating some managements, 106 (29%) did one single thing (the most common choice), 100 did 2, 78 did three and 25 did 5 or 6 (7%). Twelve individuals (5%) did 5 or more (11 did 5, and 1 each listed 6 and 7).

The most common wintering management selected was ventilation/use of a quilt box at colony top (242 individuals (58%), 94 more than last year) followed by rain shelter (159 individuals, 38%). Figure 10 shows number of individual choices and percent of each selection. Equalizing hive strength and other were the 2 selections that had best survivorship. Other choices of the 15 individuals (4%) included supplemental heat (light bulb.]/heat tape, attention to the bottom entrance including reducing it/use of slatted rack and reducing to single box to overwinter. Winterizing managements of wrapping, Vivaldi/quilt box, wind/weather break and top insulation had a slightly reduced loss.

Over the past three years no single winterizing management improved survival. However 6 managements have improved survival in 2 of the 3 years. Those managements are Equalizing colonies in the fall, Use of the quilt box/Vivaldi board/moisture trap at top of colony, an upper entrance (most Vivaldi boards have an upper entrance built into the equipment), Wrapping colonies, Wind/weather protection and other (the other items are a large mixture from reduced bottom entrance, reducing number of boxes and some means of reducing moisture). In all 3 years those doing no winterizing had heavier losses than overall.

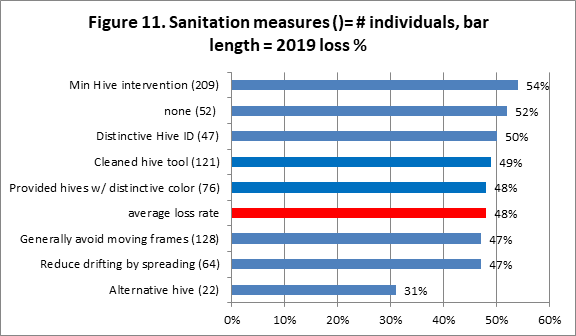

SANITATION PRACTICES: It is critical that we practice some basic sanitation (some prefer use of term bee biosecurity) in our bee care. We can do more basic sanitary practices to help insure healthy bees. We received 826 responses for this survey question. Sixty eight individuals (16%), sixteen more than last year said they did not practice any of the 6 offered alternatives; they had a loss rate of 52% compared to overall rate of 48%. One hundred fourteen (27 %) had 1 selection, 119 (29%) had 2 choices (the greatest number), 68 selected 3 managements; 13 had 5 and 3 made 6 choices. There were 2.4 selections per individual.

Minimal hive intervention (209 individuals) was the most common option selected.It could be argued that less intervention might mean reduced opportunity to compromise bee sanitation efforts of the bees themselves and that excessive inspections/ manipulations can potentially interfere with what the bees are doing to stay healthy. This option however did not demonstrate improved winter survival; the loss rate for this group was 54%, the highest for all the options. In addition to Alternatively hive, the management of generally avoiding moving frames and reducing drifting by spreading colonies were the sanitation choices that had better survival compared to overall rate.

In past three years the only sanitation choice that displayed better survival in other than a single year of occurrence was to reduce drifting. The best survival (only 22 individuals) of Alternative hive and generally avoid moving frames did not have a reduced loss rate in 2017 and 2018. Doing nothing had a high or the highest loss rate in all 3 years.

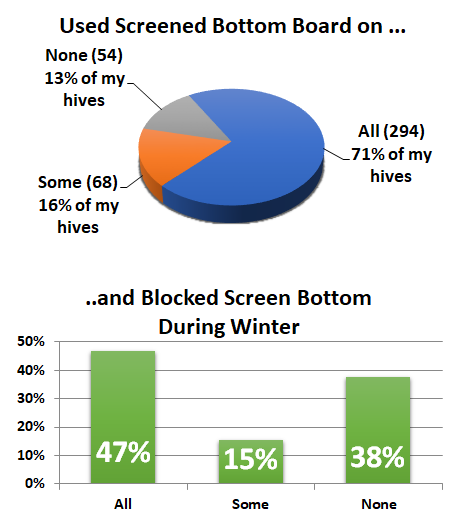

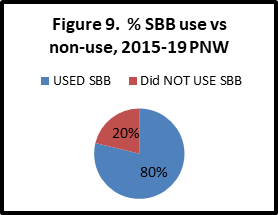

SCREEN BOTTOM BOARDS (SBB): Although many beekeepers use SBB to control varroa, BIP and PNW surveys clearly point out they are not a very effective varroa mite control tool. In this recent survey 54 individuals (16%) said they did not use screen bottom boards. This is a decrease of 11 individuals and 4% from previous year. Figure 12. This past overwintering season, the 54 non-SBB users had 233 fall colonies of which they lost 122 for 48% loss. Those beekeepers using SBB on all of their colonies had 49% loss.

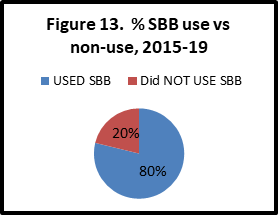

In 5 survey years 20% said they did not use SBB and 80% did use SBB on some or all of their colonies. See Figure 13 to left.Examining the four year average of SBB use, loss level of those using SBB on all or some of their colonies had a 42.8% loss level whereas for those not using SBB had loss rate of 44.2% (a 3% positive survival gain for those using SBB versus those not using them). They are very minor in improving overwinter survival.

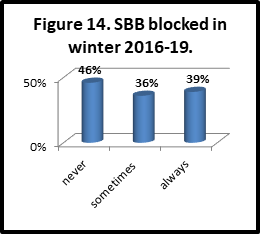

We asked if the SBB was left open (always response) or blocked during winter (bottom Figure 12). This past season 47% of individuals said they always blocked SBB during winter. They had 884 colonies in the fall and lost 503 for a 43% loss rate. One hundred forty seven individuals (38%) never blocked them during winter (never response). They had 724 colonies in the fall and lost 303 colonies =58% loss rate, 16 percentage points higher than the average of three previous years. Sixty individuals (16%) blocked them on some of their colonies. Their loss rate was 52%.

Comparing the always and sometimes left open with the closed in winter response reveals a 9 percentage point difference in favor of closing the SBB over the winter period. See Figure 14. There is no good science on whether open or closed bottoms make a difference overwinter but some beekeepers “feel” bees do better with it closed overwinter. Four years of comparison shows those closing the screen during winter did have a 9 percentage point improvement in colony survival. An open bottom, at least during the active brood rearing season, can assist the bees in keeping their hive cleaner and promote good hive ventilation.

Things that seem to improve winter success: It should be emphasized that these comparisons are correlations not causation. They are single comparisons of one item with loss numbers. Individual beekeepers do not do only one management option nor do they necessarily do the same thing to all the colonies in their care. We do know moisture kills bees, not cold, so we recommend hives be located in the sun out of the wind. If exposed, providing some extra wind/weather protection might improve survival.

Feeding, a common management, appears to be of some help in reducing losses. Feeding fondant sugar or a hard sugar candy during the winter meant lower loss levels. Providing frames of honey also meant lower loses for some individuals. Feeding of sugar syrup, the most common feeding management, did not result in lower losses overwinter but such feeding might be of great value for the spring development and/or development of new/weaker colonies. Feeding protein in form of pollen patties did slightly improve survival. The supplemental feeding of protein (pollen patties), might be of assistance earlier in the season to build strong colonies.

Winterizing measures that apparently helped lower losses for some beekeepers was equalizing strength, providing an upper entrance, a moisture trap (Vivaldi board or quilt box) and some attention to adding protection against the elements. Spreading colonies out in the apiary and painting distinctive colors or doing other measures to reduce drifting also appeared to be of some value in reducing winter losses. Avoiding movement of frames from one colony to another might also improve survival but the gain over what this interchange might accomplish might be greater than a minor advantage in survival.

It is clear that doing nothing for feeding or winterizing or sanitation resulted in the heaviest overwinter losses.

Replacing standard bottom boards for screened bottoms only marginally improved winter survival. It is apparently advantageous to close the bottom screens during winter.

Mite monitoring/sampling and control management

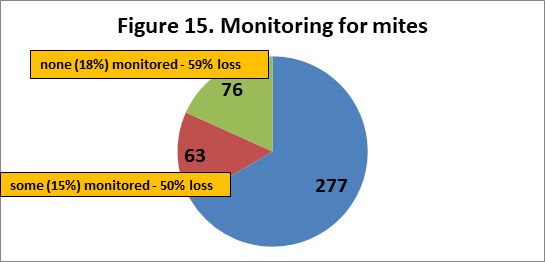

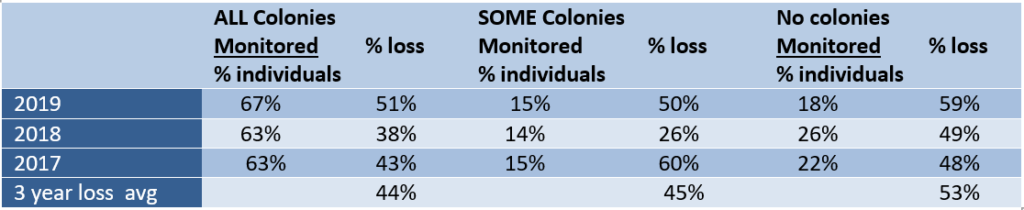

We asked percentage of Oregon hives monitored for mites during the 2018 year and/or overwinter 2018-19, whether sampling was pre- or post-treatment or both and, of the 5 possible mite sampling methods, what method was used and when it was employed. 277 individual respondents (67%), 93 more than last year and 4 percentage points higher, said they monitored all their hives. Losses of those individuals monitoring was 51%. Seventy six (18%), 1 individual less than last year but 4 percentage points less, reported no monitoring; they had a higher loss rate of 59% loss. 63 individuals reported monitoring some of their colonies; they had a 50% loss. See Figure 15.

It is obvious that monitoring alone is a means towards improved winter survival. The table below compares % individuals and % winter loss for individuals who monitored all colonies compared with those who monitored none. The 14-15% who monitored some colonies was variable but 3 year average mirrors those who monitored all colonies.

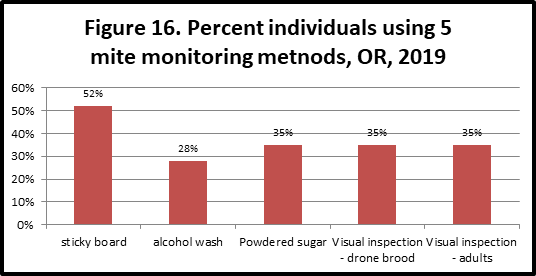

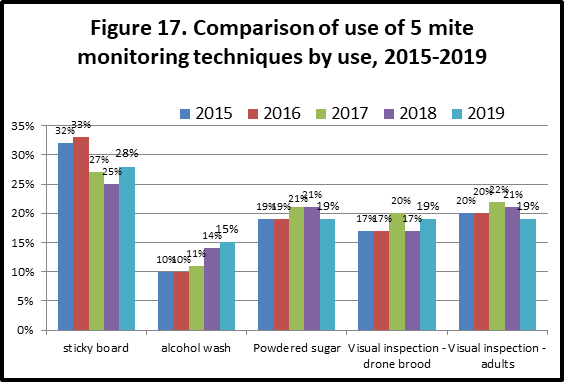

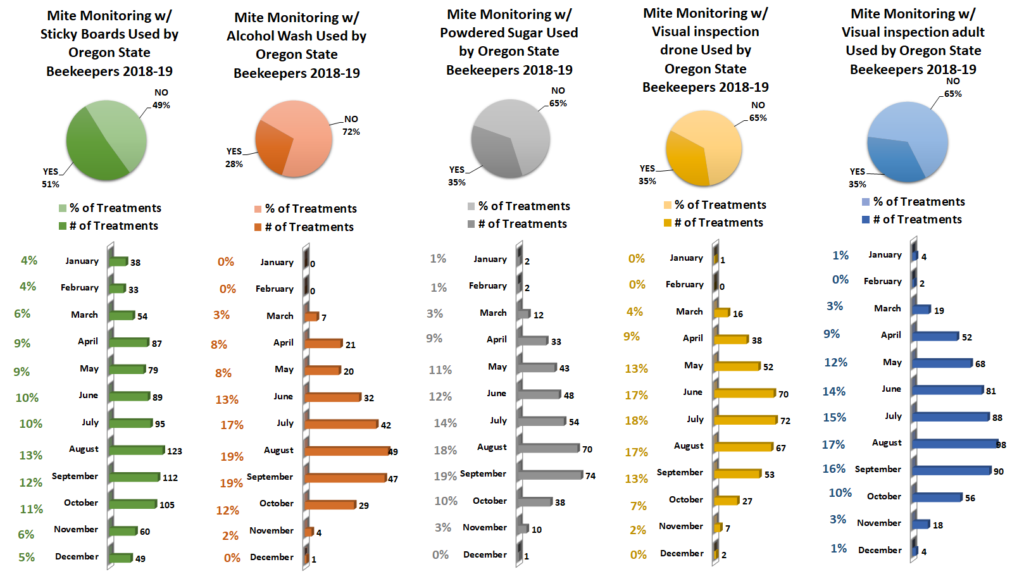

In order of popularity of use, Sticky boards were used by 174 individuals, 52% total of 340 individuals who did some or all monitoring of colonies and 28% of total selections, followed by 120 individuals (35% of individuals) using powdered sugar monitoring and visual inspection of drones; visual inspection of adults was 3 less individuals (117) but same 35%. Alcohol wash was used by 96 individuals, 28% of the respondents. In past 5 years, the use of sticky boards has decreased in use and both alcohol wash and powdered sugar shake have increased in use. Figure 15.

Individuals however are likely to use more than one monitoring technique (1.8/individual). In total choices, Sticky boards were the greatest in terms of use 28%, followed by 19% of powdered sugar and the two visual methods, each 19%; alcohol wash was used the least (15%). Alcohol wash has gained in popularity the last 5 years, now with 15% of total use and 28% of respondents indicting they are using it. Figure 16.

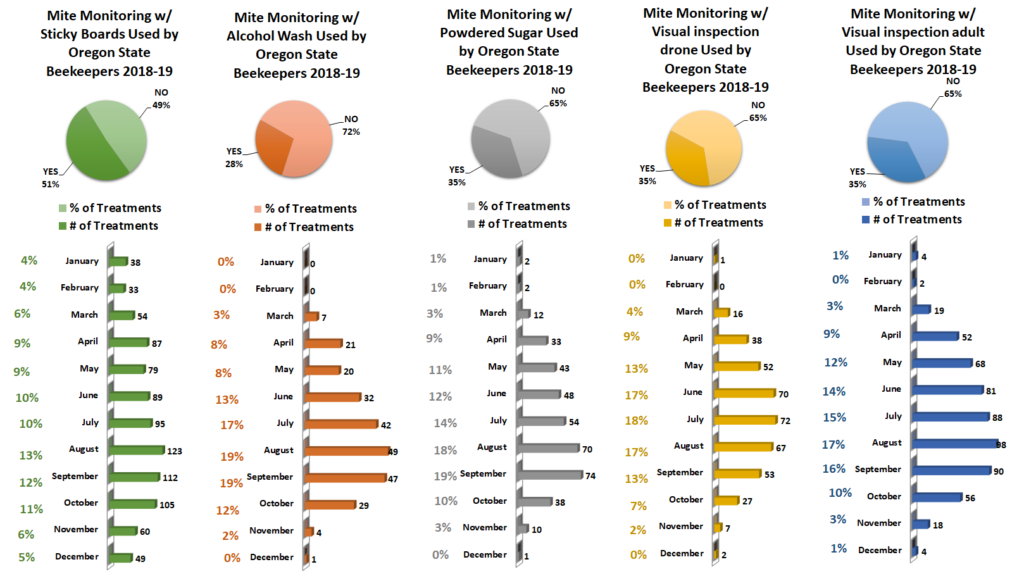

Most sampling to monitor mites was done in July – September, as might be expected since mite numbers change most quickly during these months and results of sampling can most readily be used for control decisions. See Figure 18 below for number of months each of the 5 sampling methods were used.

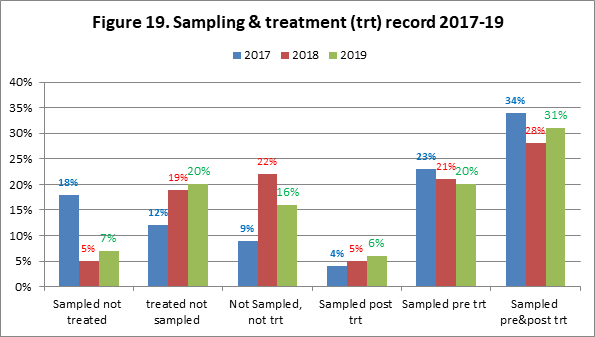

The most common sampling of respondents in 2017-18 was both pre and post-treatment (31%), as was the case the previous 2 years. Sampling just pre-treatment was similar each year; sampling just post treatment has been increasing, but is less commonly practiced (20% pre vs 6% post in 2019). Treatment without sampling has increased in last 3 years. Data for last three years in Figure 19.

It is important to KNOW mite numbers. Less effective mite monitoring methods include sticky (detritus) boards below the colony (often so much detritus drops onto a sticky board that picking out the mites can be hard, especially for new beekeepers) but sticky boards used for a day can help confirm the useful of a treatment when inserted post treatment. Visual sampling is not accurate: most mites are not on the adult bees, but in the brood. Unfortunately looking for mites on drone brood is also not effective as a predictive number but can e sued a an early warning that mites are present; if done, look at what percentage of drone cells had mites.

See Tools for Varroa Monitoring Guide www.honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroa on the Honey Bee Health Coalition website for a description of and to view videos demonstrating how best to do sugar shake or alcohol wash sampling. The Tools guide also includes suggested mite level to use to base control decisions based on the adult bee sampling. A colony is holding its own against mites if the mite sample is below 2%. It is critical to not allow mite levels to exceed 2% during the fall months when bees are rearing the fat fall bees that will overwinter. It is also the most difficult time to select a control method (if one is deemed needed) as potential treatment harm may negatively impact the colony. We are seeing more colonies suddenly disappear (abscond?) during the fall, which may be related to the treatment itself.

Mite control treatments

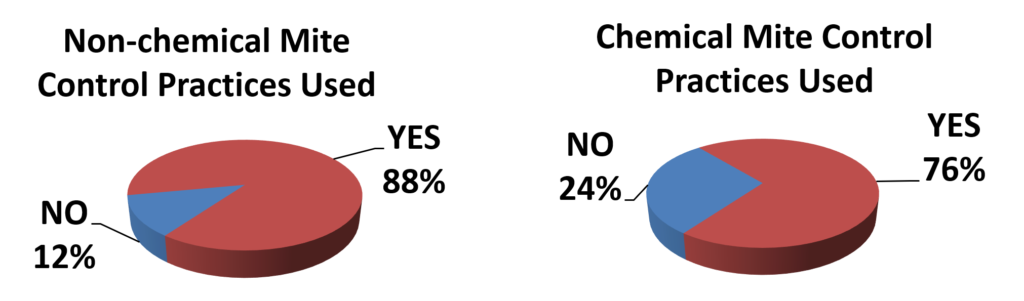

The survey asked about non-chemical mite treatments and also about use of chemicals for mite control. Fifty one individuals (12%), same percentage as last year, said they did not employ a non-chemical mite control and 99 individuals (24%), nine more than last year but 5 percentage points fewer, did not use a chemical control. See Figure 20. Those 51 individuals who did not use a non-chemical treatment reported a 50% winter loss, while those who did not use a chemical control lost 69% of their colonies. The individual options chosen for non-chemical and chemical control are discussed below.

Non-Chemical Mite Control: Of nine non-chemical alternatives offered on the survey (+ other

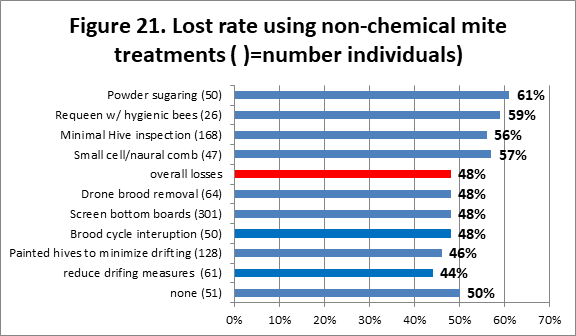

Non-Chemical Mite Control: Of nine non-chemical alternatives offered on the survey (+ other category) 89 individuals used one method, 118 used two, 95 used three, 54 used 4 or 5 and 9 individuals used 6. Use of screened bottom board was listed by 301 individuals (about 50 individuals short of number that listed use of SBB in different section of survey (see page 18). The next most common selection was minimal hive inspection (168 individuals), also up from previous year. The use of the remaining 7 selections are shown in Figure 21; number of individuals in ( ), bar length represents average loss level of those individuals using each method. Under other additions were letting bees swarm, superior genetic stock, use of natural comb and use of robber screens (1 individual with one colony that did not survive).

Three of the non-chemical alternatives have demonstrated reduced losses over past 4 year. Reducing drifting such as spreading colonies, different colony colors in apiary has demonstrated a 13% better survival, Brood cycle interruption an 11% better survival and drone brood removal a minor 2% advantage. Some control alternatives demonstrate an advantage on one or two years but overall no improvement.

Chemical Control: For mite chemical control, 99 individuals (24% of total respondents) used NO chemical treatment. Those using chemicals used at rate of 1.8/individual. One hundred thirty three individuals (42%) used one chemical, 122 used two (medium), 54 used 3 (17%), 7 used 4 and one used 5. One hundred fifty OR Beekeepers (23% of total chemical uses) indicated they most commonly utilized MAQS, formic acid, (down 10 individuals from last year), at least 6 making their own formulation to apply via shop towels, plus an additional 17 used formic pro, followed distantly by Oxalic acid vaporization (116 individuals, 18% of total chemicals used). Figure 22 illustrates number of uses ( ) and bar length indicates the loss rate for those using that chemical.

Consistently the last 3=-4 years five different chemicals have helped beekeepers improve better survival The essential oils APiguard and ApiLifeVar have consistently demonstrated the lowest loss level. Apiguard has a 31% better survival and ApilLife has a 30% better survival record over past 4 years. Apviar use, the synthetic (amitraz) has demonstrated a 29% better survival over past 4 years (2016-19). Oxalic acid vaporization over past 3 years has a 13% better survival (the survey did not differentiate Oxalic vaporization from drizzle in 2016). Formic acid demonstrated a 14% better survival but this product has changed and how we use it is changing so this information is more difficult to tease out of the data. This past season for example Formic Pro seemed to perform better than the traditional formic MAQs pads. At least indicated using formic acid in a “shop towel” delivery.

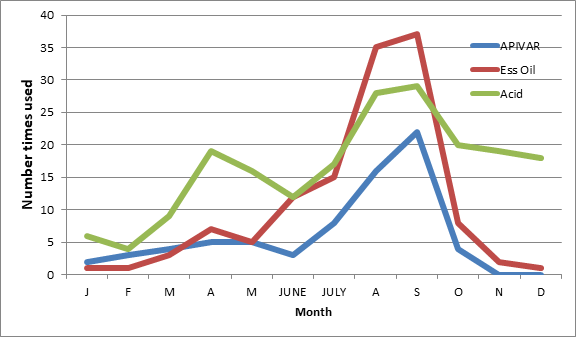

The monthly use of Apivar (blue line), essential oil (red line) or an acid (green line) is shown in Figure 23 for 2016-17 season. Further review is needed to determine if the timing of treatments was more effective than at other times for the various chemicals.

Antibiotic use

Eighteenn individuals (4%) used Fumigillan (for Nosema control); their loss rate was 35%. One individuals (one less than last year) indicated use of terramycin.

Queens

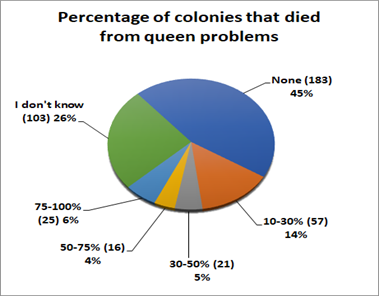

We hear lots of issues related to queen “problems”. Recall under the questions asking the reasons why colonies didn’t survive that 88 individuals, 27% believed queen failure as one of their selections. In Section 8 of the survey we asked what percentage of loss could be attributed to queen problems. One hundred twenty nine individuals subdivided queen related issues from 10 to 100% of their hives. One hundred eighty three (44) said none; an additional 103 individuals (24.5%) said they didn’t know. The number and percent expressed is shown in pie chart Figure 24.

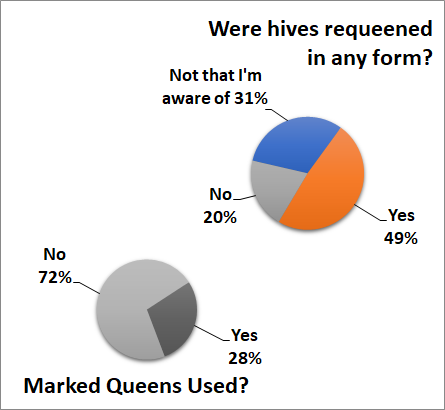

Queen events can be a significant factor contributing to a colony not performing as expected. We asked if you had marked queens in your hives. One hundred sixteen (28%) said yes. The related question then was did you or your bees replace their colony queen? Forty-nine percent (204 individuals) said yes, 31% said no. and the remainder ‘not that that I am aware of.’ Figure 25.

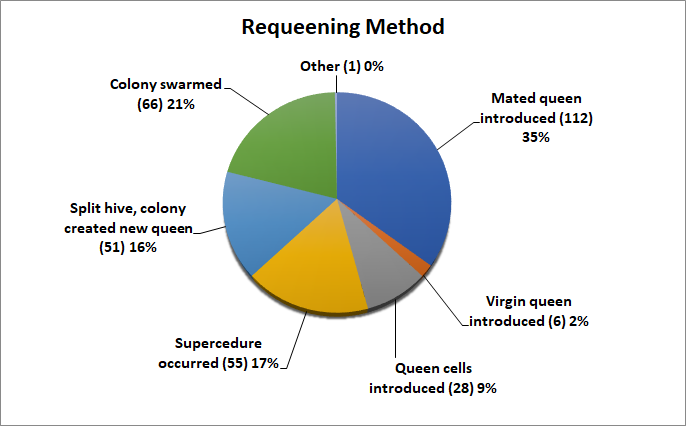

One technique to reduce mite buildup in a colony is to requeen/break the brood cycle. The question “How did bees/you requeen“ received 318 responses (more than one option could be checked) as illustrated in Figure 26. Although over one-third of respondents indicated their bees were requeened with a mated queen more than one half (54%) indicated it was the bees that requeen via swarming, supersedure or emergency rearing. That means too few were seeking to use this valuable tool for mite control. Figure 21 illustrating the non-chemical mite control of brood break (50 individuals 48% loss) or use of hygienic queens (26 individuals 59% loss level) reinforces that this manipulation is not heavily utilized.

This survey is designed to ‘ground truth’ the larger, national Bee Informed loss survey. Some similar information is additionally available on the BeeInformed website www.beeinformed.org and individuals are encouraged to examine that data base as well. Recall that the BeeInformed survey is measuring the larger scale OR beekeepers not the backyarders (figure 6. )Reports for individual bee groups are customized and posted to the PNW website.

We intend to continue to refine this instrument each season and hope you will join in response next April. If you would like a reminder when survey is open please email us at [email protected] with “REMINDER” in the subject line. We have a blog on the pnwhoneybeesurvey.com and will respond to any questions or concerns you might have.

Thank You to all who participated. If you find any of this information of value please consider adding your voice to the survey in a subsequent season.

Dewey Caron and Jenai Fitzpatrick, June 2019

Washington backyard beekeeper Winter Losses 2018-19 Dewey Caron

Ninety eight Washington beekeepers (6 fewer than last year) supplied information on winter losses and several managements related to bee health with an electronic honey bee survey instrument www.pnwhoneybeesurvey.com. Overwintering losses of small scale Washington beekeepers were once again elevated.

Figure 1 shows total OR and WA response by local association. Statewide loss level is highlighted. Number individuals ( ) to left of association name is number of respondents, bar length is % overwinter losses by club. Total fall colony response was 416 OR and 98 WA individuals; survey included 551 WA fall colonies.

The WA respondents to the electronic survey managed up to 40 fall colonies. Fourteen individuals had 1 colony, 25 respondents had 2 colonies (the greatest number) and 16 individuals had 3 colonies (=55 individuals, 56% of total respondents had 1, 2 or 3 colonies), 21 individuals had 4 to 6 colonies, 4 had 7-9 colonies and 18 individuals had 10+ colonies. When loss levels were computed the 1-3 colony owners had a 63% loss, the 4-6 colony owners had 49% loss level and the 10+ individuals had 60% loss of colonies in 2018-19 overwintering period.

Thirty eight WA individuals (39% of respondents) had 1 or 2 years of experience; 32 individuals had 33% had 4 – 6 years’ experience (medium number = 4), 12individuals had 7-9 years experience and 16 had 10+ years with 39 the greatest. When loss level was correlated the individuals with 1-3 years experience had 62% loss level, the 4-6 years experience group had 61% loss and the 10+ years experience group had a 71% loss.

Seventy one (73%) of WA beekeepers had an experienced beekeeper mentor available as they were learning beekeeping. This percentage was up from 62% the previous year.

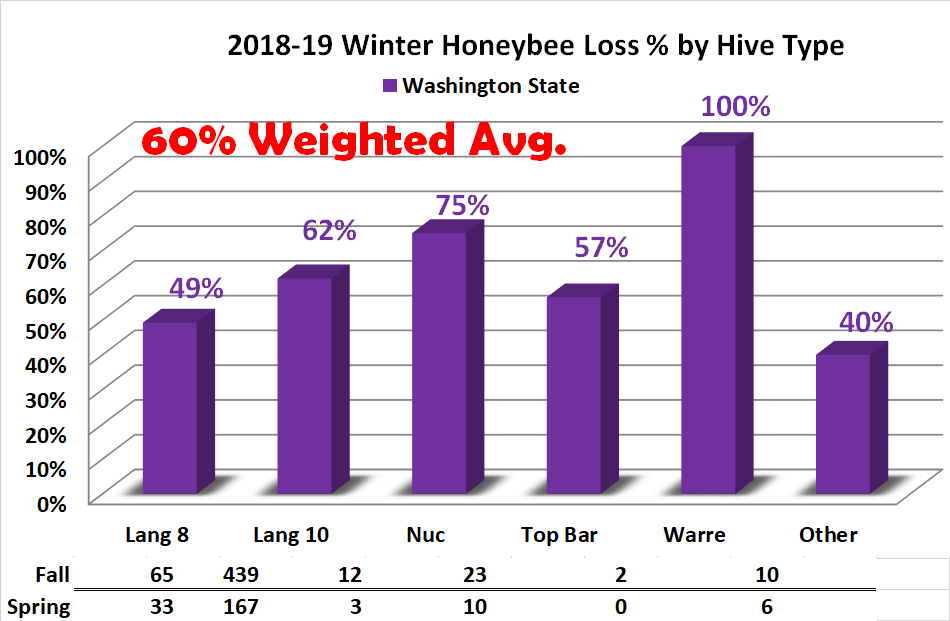

Total WA backyard beekeeper overwinter loss = 60% loss.

The WA survey overwintering loss statistic was developed by our asking number of fall colonies and surviving number in the spring by hive type. Results, shown in Figure 2 bar graph, illustrates overwintering losses of 98 total WA beekeeper respondents. Langstroth 8 and 10 frame beehives plus nucs (94% of total) had heavier average losses (61%) than the alternative (Top bar, Warré and other) hives (54%).

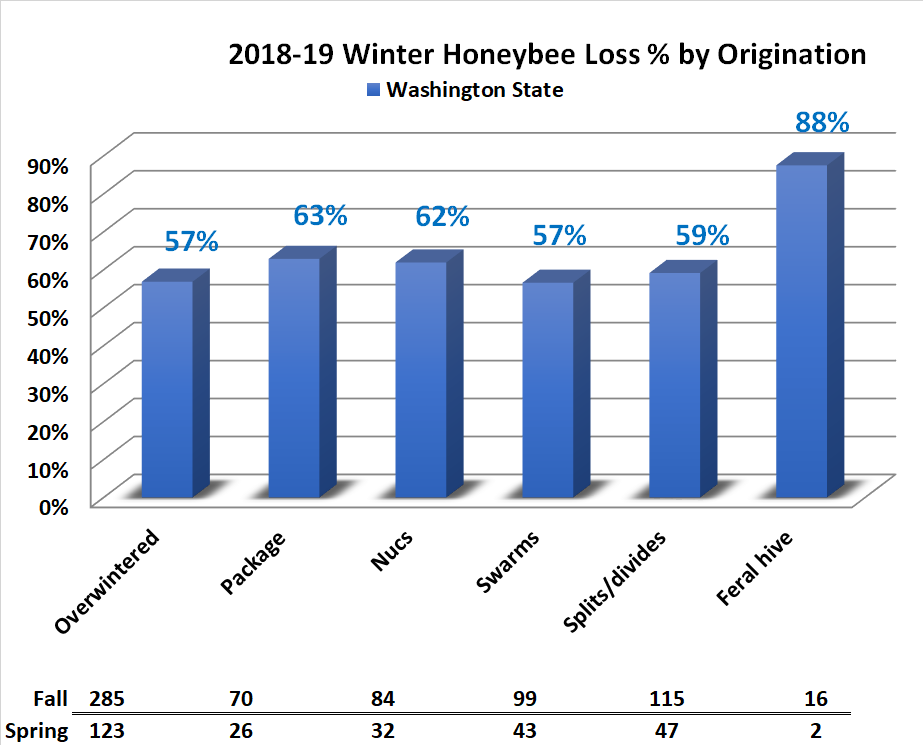

Origination: We also asked about hive loss by origination. Data shown in Figure 3. All but feral hive transfers had similar loss level.

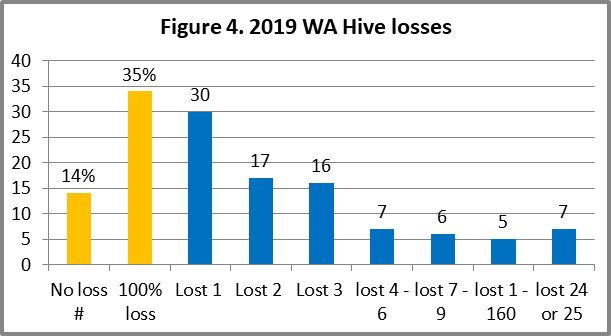

Among 98 WA beekeepers 15 individuals (15%) maintained more than one hive type. For the total WA beekeepers, 14 (14%) had no loss and 34 individuals (35%) had total loss. Thirty WA individuals lost 1 colony, 17 individuals lost 2 colonies and 16 individuals lost 3 colonies (75% of individuals with losses). Eight (8) individuals lost 12 or more colonies; highest loss was 25 colonies. Data in Figure 4.

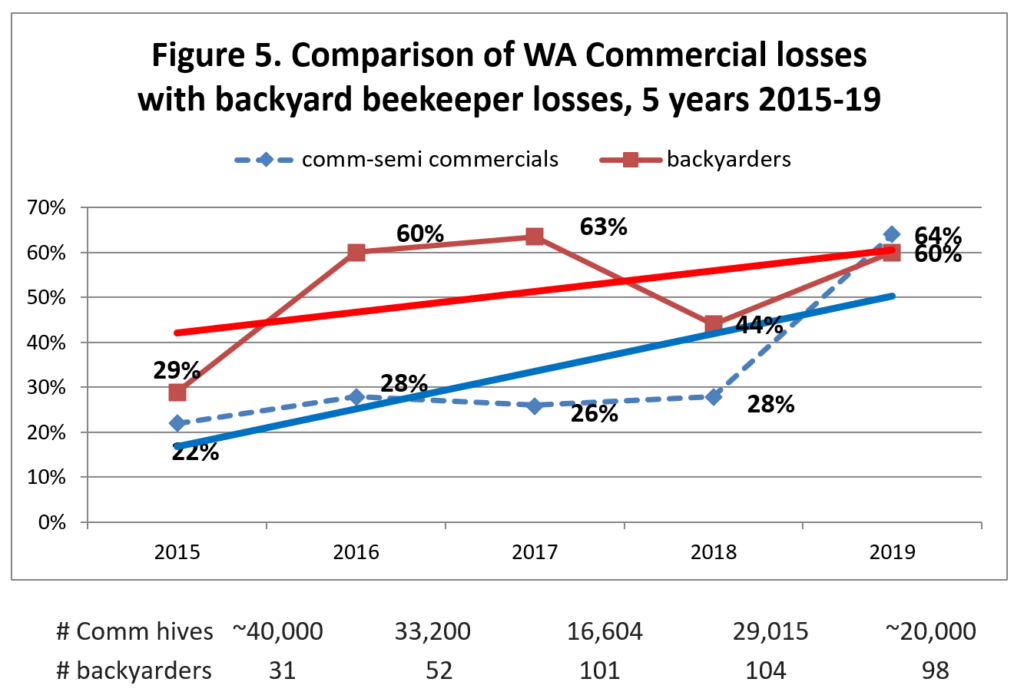

Comparison of backyarders and commercial/semi-commercial beekeepers

A different (paper) survey instrument was mailed to Pacific Northwest (PNW) semi-commercial (50-500 colonies) and commercial beekeepers (500+) asking about their overwintering losses. Comparison is shown in Figure 5 below with approximate number of colonies represented by the commercial/semi-commercial beekeepers and number of individual backyarder survey respondents. Also shown is he trend line of losses of both groups.

Backyard losses have consistently been higher, in some years double the losses of larger-scale beekeepers but this past year the commercial losses were higher than backyarder losses. Number of colonies of the commercial keepers returning surveys were lower this past season (returns were an estimated 26% of the NASS estimate of 77,000 colonies in the state) which may explain the reversal. The reasons backyarders have had higher losses 4 of the past 5 years are complex. Commercial and semi-commercial beekeepers examine colonies more frequently and they examine them first thing in the spring as they take virtually all of their colonies to Almonds in February. They also are more likely to take losses in the fall and are more pro-active in varroa mite control management.

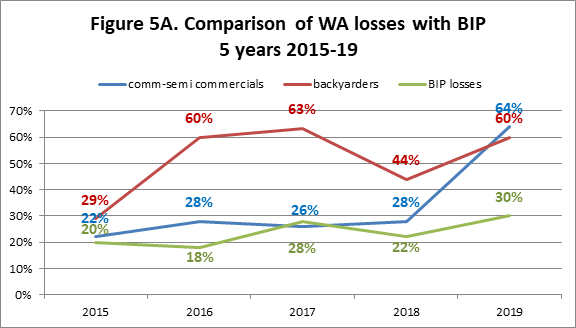

The PPNW survey was conducted in part to “ground truth” the annual BeeInformed Survey (BIP) also conducted during April. This survey recorded the highest loss level of past five years (30% loss for 2018-19 winter is a preliminary number that may change as the data is examined in further detail).

The BIP survey includes a mailed survey to larger-scale beekeepers and an electronic survey to which any Washington beekeeper can submit their data. Losses reported for a state include colonies of migratory beekeepers who reported WA as one of their yearly locations. The BIP survey for the 2015-18 annual surveys (2019 data not yet available) reports receiving responses from 90 to 95% of respondents exclusive to Washington but loss is computed on no more than 4% of the colonies exclusive to Washington state, indicating the BIP tally is primarily of commercial beekeepers (whom almost exclusively move to CA for pollination of almonds).

Graph 5A compares PNW with BIP survey clearly showing that the BIP survey loss numbers are those of the commercial beekeepers of Washington and not the backyarder losses. The same hold true for OR and ID comparisons. Numbers of respondents & colony numbers for the BIP Washington survey is as follows: 2015=158 indiv,~108,000 colonies; 2016 136 indiv, ~29,000 colonies; 2017=113 indiv,~73,500colonies and 2018=134 indiv, ~52,000 colonies (data for 2019 not yet available – will be published on site https://bip2.beeinformed.org/loss-map/)

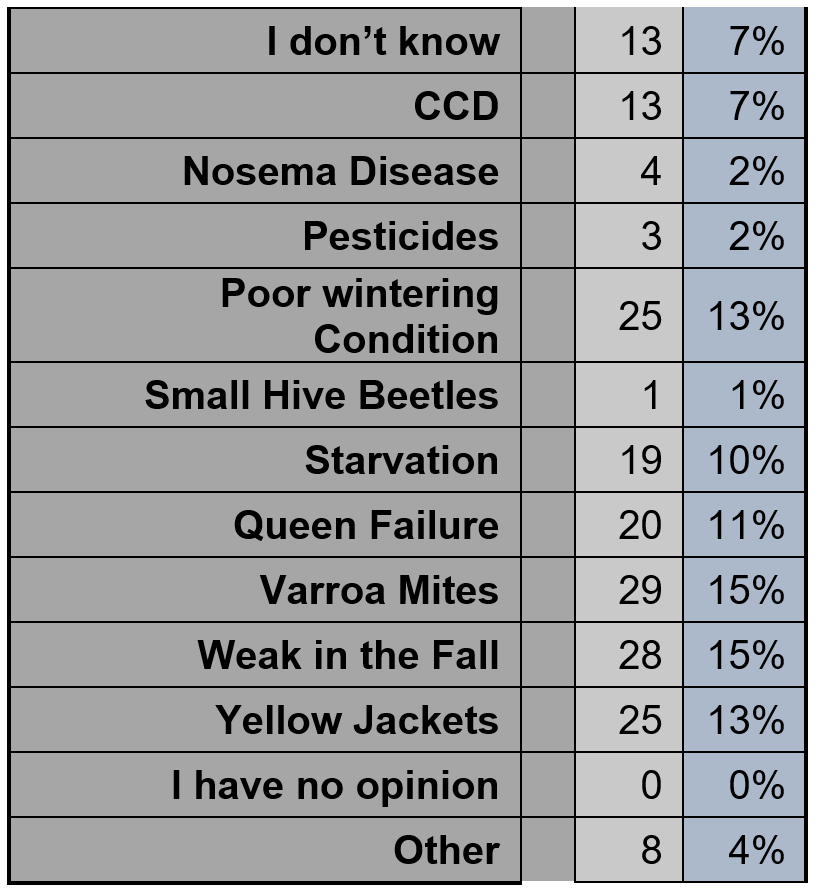

Self-reported “reasons” for colony losses: We asked survey takers who had winter losses for the “reason” for their losses. More than one selection could be chosen. In all there were 188 WA selections (1.9/individual) provided. Weak in the fall (21 individual choices), Varroa mites (each 15%), poor wintering conditions (25 choices) and yellow jackets, both 13% were most common choices. The table shows number and % of selections.

There is no easy way to verify reason(s) for colony loss. Colonies in the same apiary may die for different reasons. Doing a dead colony examination (necropsy) is the first step in seeking to solve the continuing heavy loss problem. More attention to colony strength and checking stores to help avoid winter starvation will help reduce some of the losses. Control of varroa mites will also help reduce losses.

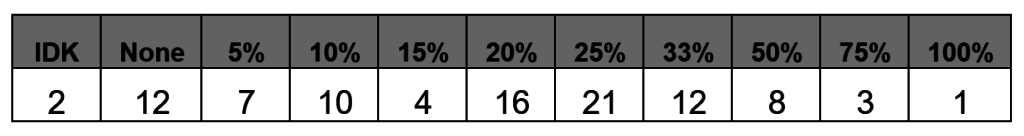

Respondents were asked to select an acceptable loss level, being offered several categories to check. Twelve individuals said zero, while 7 said 5% and 10 indicated 10%, 20% was medium; 12 individuals (12.5% said 50% or more was an acceptable loss level.

Why do colonies die? There appears to be no single reason for loss and a good deal of variance in opinion as to what might be an acceptable loss level. We are dealing with living animals which are constantly exposed to many different challenges, both in the natural environment and the beekeeper’s apiary. Major factors are thought to be mites, pesticides, declining nutrition adequacy of the environment and diseases, especially viruses and Nosema. Management, failure to do something or doing things incorrectly, remains a factor in our losses.

What effects our alteration to the bee’s natural environment and other external factors play in colony losses are not at all clear.

Langstroth wrote about the importance of taking winter losses in fall management saying if the beekeeper neglects such attention to his/her colonies 45% loss levels may occur, depending upon variable environmental conditions. It can be argued that losses of 30, 40, 50% or more might be the new “normal.” Older, more experienced beekeepers recall when loss levels were 15% or less. Honey production fluctuates each year but, once again, seem to be declining on average. Numbers of U.S. bee colonies have declined since the 1940s, returning to numbers for 100 years ago, although numbers for the last 3 decades have not changed. Worldwide numbers of bee colonies are steadily increasing.

So there is no simple answer to explain the levels of current losses nor is it possible to demonstrate that they are excessive for all the issues facing honey bees in the current environment.

Colony Management

We asked in the survey for information about some managements practiced by respondents. Multiple responses were accepted. The survey inquired about feeding practices, wintering preparations, sanitation measures utilized, screen bottom board usage, mite monitoring, both non-chemical and chemical mite control techniques and queens. Respondents could select options and there was always a none and other selection possible. This analysis seeks to compare responses of this past season to previous survey years.

Most Washington beekeepers do not perform just one management to their colony (ies) toward improving colony health and overwintering success. This analysis however is mainly of a single factor equated with loss level. Such analysis is correlative and doing a similar management as fellow beekeepers does not necessarily mean you too will improve success.

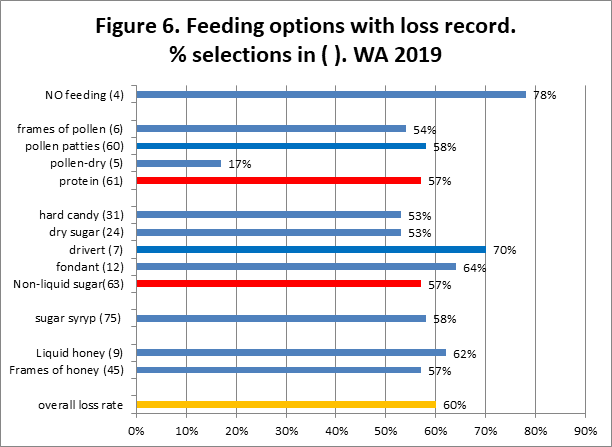

FEEDING: Washington survey respondents checked 278 feeding options = 3.0/individual. Four individuals (4%) indicated no feeding, 15 selected a single choice and had 72% loss level, 21 (21% of respondents) indicated 2 choices and had a 74% loss, 31 (he greatest choice and also the median) made 3 choices and reported a 62% loss level. Seventeen respondents had 4 choices with a 57% loss 6 individuals had 5 choices with the lowest loss level 21%; 2 individuals each made 6 and 7 choices with 67% loss. More choices seem to improve survival.

The choices, with percent of individuals making that selection is in ( ); bar length indicates loss level of individuals doing this management. Figure 6. Those bar lengths to left of 60% had better survival while those to right had greater loss level.

Four individuals said they did NO FEEDING. They had 11 fall colonies and realized a 78% loss, 18 percentage points higher than overall loss level. For individuals indicating one or more feeding managements, feeding sugar syrup was the most common feeding option of respondents (75 individuals, 75% of respondents). Their loss rate was 58%, statistically same as overall average. Percent of individuals feeding protein (61%) and non-liquid sugar was 63%); both collectively had slightly better survival rate. Some selections, most notably dry pollen and dry sugar and hard candy had lower losses than the average overall loss rate.

For the last 3 years of losses individuals doing no feeding had poorer survival all 3 years, including this year with 78% loss reported by the 4 individuals who indicated they did not feeding. Individuals that fed sugar syrup had marginal lower loss level in 2 of three years as did those using frames of honey to feed bees Individuals feeding non–liquid sugar in the form of fondant and hard candy likewise had lower losses in at least one year (fondant – 13 individuals had 22 percentage point lower losses in 2017) and hard candy in two of the three years (31 individuals had 7 percentage point better survival this season and 22 percentage point improvement by 13 individuals in 2018. ) For individuals feeding protein, protein patty users showed slightly better survival in 2 of 3 years; dry pollen feeders had significantly better survival in two one of the three years, including this past year when 5 individuals had only a 17% loss, 43 percentage point improvement compared to overall loss. In 2016 the gain was 40 percentage points but only 2 individuals reported use of dry pollen.

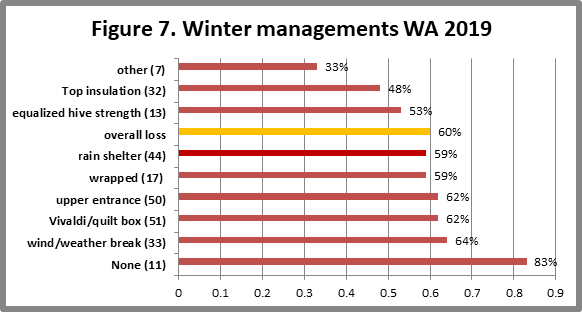

WINTERING PRACTICES: We received 256 responses (2.9/individual) about WA beekeeper wintering management practices (more than one option could be chosen). Eleven individuals (11%) percent of the respondents indicated none of the several listed wintering practices was done; these individuals had an 83% winter loss, 23 percentage points higher loss than overall loss of 60%. For those indicating some managements, 18 (18%) did one single thing had 83% loss level, 2 respondents had 46% loss, 20 had 3 choices with a 58% loss (the medium choice), 18 did (57% loss), 6 did 5 (53% loss); 3 had 6 choices 78% loss and 1 had 7 responses 80%.

The most common wintering management selected was ventilation/use of a quilt box at colony top (51 individuals (51%), followed by upper entrance (50 individuals, 38%). Figure 7 shows number of individual choices and percent of each selection. Equalizing hive strength, top entrance and other were the 3 selections that had best survivorship. Other choices of the 7 were entrance reduction (6 individuals), more ventilation (2 individuals).

Over the past three years a couple of winterizing management improved survival. Those doing no winterizing had slightly higher losses (this year a 23 percentage point difference). Equalizing hive strength in the fall demonstrated lower loss levels in all three recent winter periods (7 percentage points this past winter, 9 percentage points last winter and 6 percentage points in 2016-17 winter).Top insulation has demonstrated lower loss in two of the three years, in the most recent winter 32 individuals realized a 12 percentage point improvement. Ventilation above the colony (Vivaldi Board/quilt box) demonstrated improved survival two of the three winters but not this past one (2 percentage point higher loss).

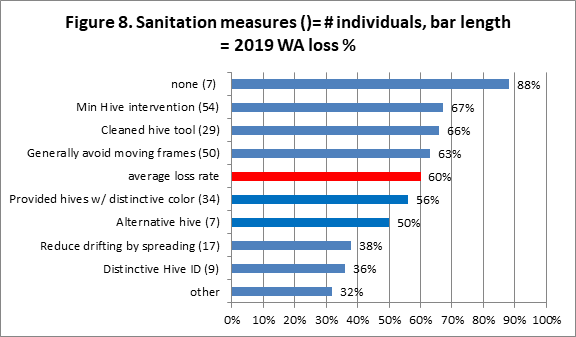

SANITATION PRACTICES: It is critical that we practice some basic sanitation (some prefer use of term bee biosecurity) in our bee care. We can do more basic sanitary practices to help insure healthy bees. We received 211 responses for this survey question. Seven individuals (7%), said they did not practice any of the 6 offered alternatives; they had a loss rate of 88% compared to overall rate of 60%. Twenty seven individuals (27 %) had 1 selection and had 46% loss, 29 (29%) had 2 choices (the greatest number) with 57%, 24 selected 3 managements with 61%; 8 had 4 (66% loss) and 3 made 5 choices (68% loss). There were 2.3 selections per individual.

In two of three years doing none of these managements resulted in improved survival; this was not the case last winter when the 7 individuals doing nothing had very high losses of 88%. Using an alternative hive resulted in lower losses in two of three winters but this was not borne out by examining statistics of Figure 2 (loss by hive type). Providing hives with color, distinctive hive ID and measures to reduce drifting were helpful managements this past winter but not in the previous two seasons though their loss level was same as or similar to overall loss level (these three choices were not always available in previous survey years).

SCREEN BOTTOM BOARDS (SBB): Although many beekeepers use SBB to control varroa mites, BIP and PNW surveys clearly point out they are not or at best not a very effective varroa mite control tool. In this recent survey 16 Washington individuals (16%) said they did not use screen bottom boards. This past overwintering season, the 16 non-SBB users had 87 fall colonies of which they lost 47 for 54% loss. Those 65 beekeepers using SBB on all of their colonies had 64% loss. The 17 individuals using SBB on some of their colonies had 57% loss.

In 5 survey years 20% said they did not use SBB and 80% did use SBB on some or all of their colonies. See Figure 9.

Examining the five year average of SBB use, loss level of those using SBB on all or some of their colonies had a 42.8% loss level whereas for those not using SBB had loss rate of 44.2% (a 3% positive survival gain for those using SBB versus those not using them). They are very minor in improving overwinter survival.

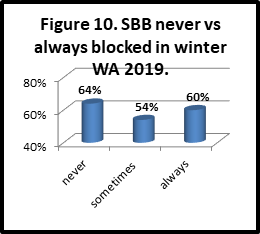

We asked if the SBB was left open (always response) or blocked during winter (bottom Figure 10). This past season 46 individuals (51%) said they always blocked SBB during winter. They had a 60% loss rate, average loss rate for statewide. Thirty seven individuals said they never blocked SBB and had loss rate of 64%. Seven individual (8%) blocked them on some of their colonies. Their loss rate was 54%.

There is no good science on whether open or closed bottoms make a difference overwinter but some beekeepers “feel” bees do better with it closed overwinter. Comparing the always and sometimes left open with the closed in winter response reveals a slight percentage point difference in favor of closing the SBB over the winter period. See Figure 10. This relationship has been consistent over the past five years averaging nearly a 10 percentage point advantage when the SBB is closed during the winter. An open bottom, at least during the active brood rearing season, can assist the bees in keeping their hive cleaner and promote good hive ventilation.

Things that seem to improve winter success: It should be emphasized that these comparisons are correlations not causation. They are single comparisons of one item with loss numbers. Individual beekeepers do not do only one management option nor do they necessarily do the same thing to all the colonies in their care. We do know moisture kills bees, not cold, so we recommend hives be located in the sun out of the wind. If exposed, providing some extra wind/weather protection might improve survival.

Feeding, a common management, appears to be of some help in reducing losses. Feeding fondant sugar or a hard sugar candy during the winter meant lower loss levels. Providing frames of honey or sugar syrup, the most common selection, also meant slightly lower loses for some individuals but these basic managements are useful in other ways such as for spring development and/or development of new/weaker colonies besides insuring better winter survival.

Feeding protein in form of pollen patties did slightly improve survival. The supplemental feeding of protein (pollen patties), might be of assistance earlier in the season to build strong colonies.

Winterizing measures that apparently helped lower losses for some beekeepers was equalizing strength, providing an upper entrance, a moisture trap (Vivaldi board or quilt box) and some attention to adding protection against the elements. Spreading colonies out in the apiary and painting distinctive colors or doing other measures to reduce drifting also appeared to be of some value in reducing winter losses. Avoiding movement of frames from one colony to another might also improve survival but the gain over what this interchange might accomplish might be greater than a minor advantage in survival.

It is clear that doing nothing for feeding or winterizing or this past season in sanitation resulted in the heaviest overwinter losses.

Replacing standard bottom boards for screened bottoms only marginally improved winter survival. It is apparently advantageous to close the bottom screens during winter.

Mite monitoring/sampling and control management

We asked percentage of Washington hives monitored for mites during the 2018 year and/or overwinter 2018-19, whether sampling was pre- or post-treatment or both and, of the 5 possible mite sampling methods, what method was used and when it was employed. Sixty eight individual respondents (68%) said they monitored their hives. Losses of those individuals monitoring was 58%. Twenty four (24%), reported no monitoring; they had a higher loss rate of 74% loss. Six individuals monitored some with loss rate 57%. Montoring helps.

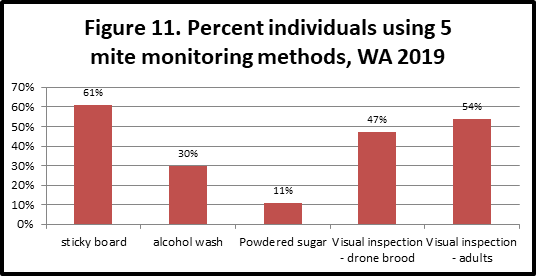

In order of popularity of use, Sticky boards were used by 45 individuals, 61% total of 74 individuals who did some or all monitoring of colonies and 46% of total selections, followed by 40 individuals (54% of individuals doing monitoring) that used visual inspection of adults and 35 individuals (47%) that used visual inspection of drones brood. The two most accurate means of determining mite load, alcohol wash was used by 22 individuals (30%) and powdered sugar was employed by 8 respondents (11%). Figure 11.

Individuals however are likely to use more than one monitoring technique (1.8/individual). In total choices, Twenty six used a single monitoring method, 19 used two, 22 used three and 5 used 4 sampling methods.

Most sampling to monitor mites was done in July – September, as might be expected since mite numbers change most quickly during these months and results of sampling can most readily be used for control decisions. See Figure 12 below for number of months each of the 5 sampling methods were used.

Figure 12

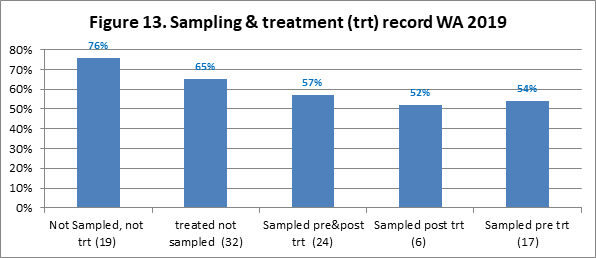

The most common sampling of respondents in 2018-19 was treated but did not sample (32% individuals) followed by both pre and post-treatment (24%). Nine individuals said they did not sample or treat. Data for loss level % shown in Figure 13; # respondents in ( ).

It is important to KNOW mite numbers. Less effective mite monitoring methods include sticky (detritus) boards below the colony (often so much detritus drops onto a sticky board that picking out the mites can be hard, especially for new beekeepers) but sticky boards used for a day can help confirm the useful of a treatment when inserted post treatment. Visual sampling is not accurate: most mites are not on the adult bees, but in the brood. Unfortunately looking for mites on drone brood is also not effective as a predictive number but can be used as an early warning that mites are present; if done, look at what percentage of drone cells had mites.

See Tools for Varroa Monitoring Guide www.honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroa on the Honey Bee Health Coalition website for a description of and to view videos demonstrating how best to do sugar shake or alcohol wash sampling. The Tools guide also includes suggested mite level to use to base control decisions based on the adult bee sampling. A colony is holding its own against mites if the mite sample is below 2%. It is critical to not allow mite levels to exceed 2% during the fall months when bees are rearing the fat fall bees that will overwinter. It is also the most difficult time to select a control method (if one is deemed needed) as potential treatment harm may negatively impact the colony. We are seeing more colonies suddenly disappear (abscond?) during the fall, which may be related to the treatment itself.

Mite control treatments

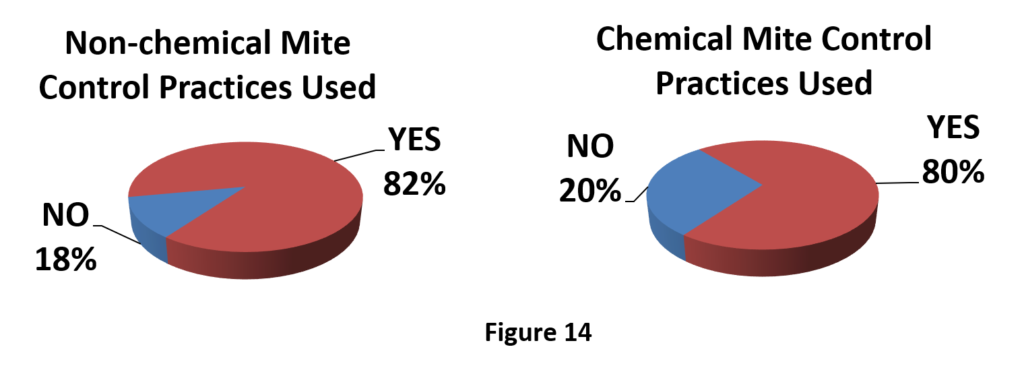

The survey asked about non-chemical mite treatments and also about use of chemicals for mite control. Eighteen individuals (18%), 3 individuals more than last year, said they did not employ a non-chemical mite control and 20 individuals (20%), fourteen fewer than last year, did not use a chemical control. See Figure 14. Those 18 individuals who did not use a non-chemical treatment reported a 51% winter loss, while those who did not use a chemical control lost 77% of their colonies. The individual options chosen for non-chemical and chemical control are discussed below.

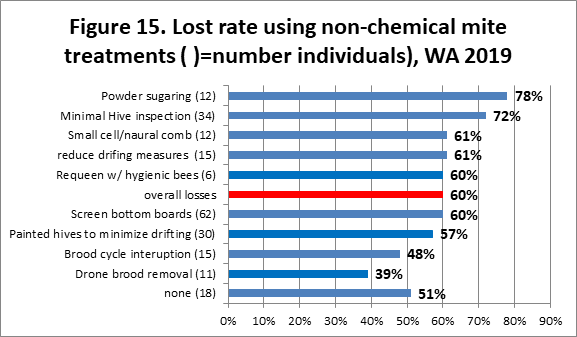

Non-Chemical Mite Control: Of nine non-chemical alternatives offered on the survey (+ other category,) 27 individuals used one method and had an 85% loss, 20 used two (53% loss level), 14 used three (60% loss), 8 used 4 (67% loss), and 8 also used 5 with a 53% loss. The 3 using 6 selections had 55% loss. Use of screened bottom board was listed by 62 individuals (20 individuals short of number that listed use of SBB on all or some of their colonies in a different section of survey (see page 10). The next most common selection was minimal hive inspection (34 individuals). The use of the remaining 7 selections are shown in Figure 15; number of individuals in ( ), bar length represents average loss level of those individuals using each method. Under other additions was attempted heat treatment by 1 individual who lost both of their fall colonies.

Two of the non-chemical alternatives demonstrated reduced losses this past year – brood cycle interruption and Drone brood removal. Painting hives to reduce drifting also showed a 3 percentage point reduced loss. Painting hives reduced loss by 4 percentage points last year and brood cycle interruption was the best performing alternative last year. Requeening with hygienic queens used by 3 individuals in 2016-17 and one individual in 2017-18 as a non-chemical treatment had the same loss level as overall in 2018-19 wintering period.

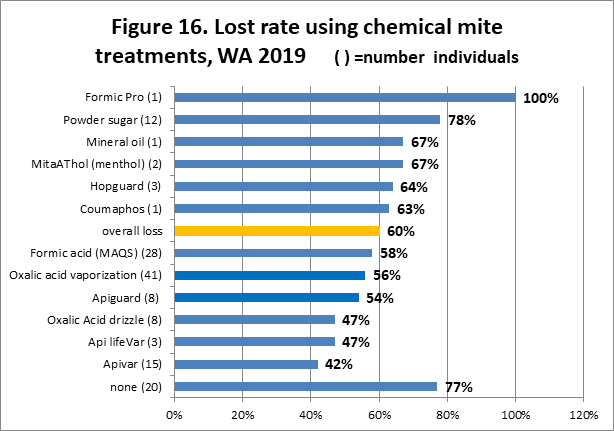

Chemical Control: For mite chemical control, 20 individuals (20% of total respondents) used NO chemical treatment; these individuals had a 77% loss level. Those using chemicals used at rate of 1.6/individual. Fifty one individuals (51%) used one chemical and had 64% loss, 19 used two and showed better survival of 40% loss, 6 used 3 (517% loss), 1 used 4 (33% loss)and the single individual that used 6 had a 57% survival. Forty one individuals (53% of total chemical uses) indicated they most commonly utilized Oxalic acid vaporization and 28 respondents used MAQS, formic acid, (one indicated use of Formic Pro), followed distantly by Oxalic acid drizzle (8 individuals, 10% of total chemicals used). The 12 individuals that used powdered sugar had losses same as those who indicated use of no chemicals. Figure 16 illustrates number of uses ( ) and bar length indicates the loss rate for those using that chemical.

Consistently the last 3-4 years five different chemicals have helped beekeepers realize better survival. The essential oils APiguard and ApiLifeVar have consistently demonstrated the lowest loss level. Apiguard has a 31% better survival and ApiLifeVar has a 30% better survival record over past 4 years. Apivar use, the synthetic (amitraz), has demonstrated a 29% better survival over past 4 years (2016-19). Oxalic acid vaporization over past 3 years has a 13% better survival (the survey did not differentiate Oxalic vaporization from drizzle in 2016). Formic acid demonstrated a 14% better survival but this product has changed and how we use it is changing so this information is more difficult to tease out of the data. This past season for example Formic Pro seemed to perform better than the traditional formic MAQs pads, although the one identified user of Formic Pro did not have any survival . At least indicated using formic acid in a “shop towel” delivery.

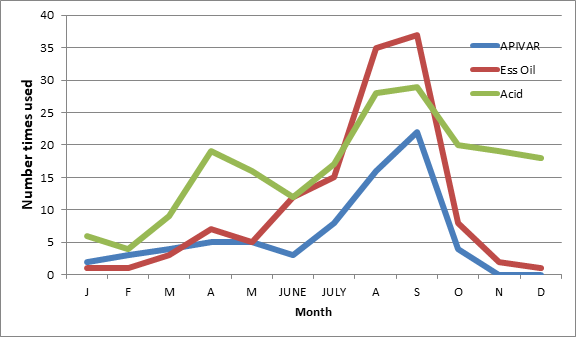

The monthly use of Apivar (blue line), essential oil (red line) or an acid (green line) is shown in Figure 17 for 2016-17 season. Further review is needed to determine if the timing of treatments was more effective than at other times for the various chemicals.

Antibiotic use

Nine individuals (9%) used Fumigilian (for Nosema control); their loss rate was 68%, slightly higher than overall loss level. One used nosevet in addition. Two indicated use of essential oil (One IDed as lemongrass) and had a 61% loss. One individual indicated use of terramycin (63% loss)and 2 said they used Tylan (38% loss) for bacterial brood disease control.

Queens

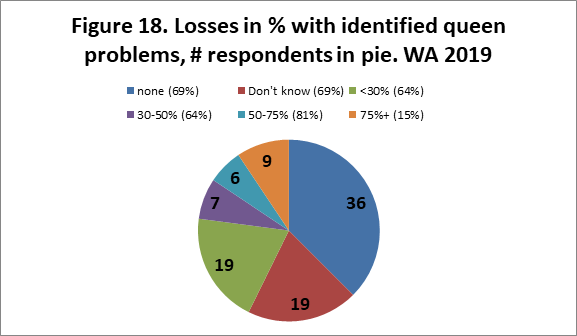

We hear lots of issues related to queen “problems”. Recall under the questions asking the reasons why colonies didn’t survive that 20 individuals, 20% believed queen failure as one of their selections. In Section 8 of the survey we asked what percentage of loss could be attributed to queen problems. Forty one individuals subdivided queen related issues from 10 to 100% of their hives; the majority (19 individuals) indicating up to 30% Thirty six (36%) said none; an additional 19 individuals (19%) said they didn’t know. The number of respondents and percent losses of each is shown in pie chart Figure 18.

Queen events can be a significant factor contributing to a colony not performing as expected. We asked if you had marked queens in your hives. Twenty eight (28%) said yes. The related question then was did you or your bees replace their colony queen? Fifty three said yes, 28 said no. and the remainder ‘not that that I am aware of.’

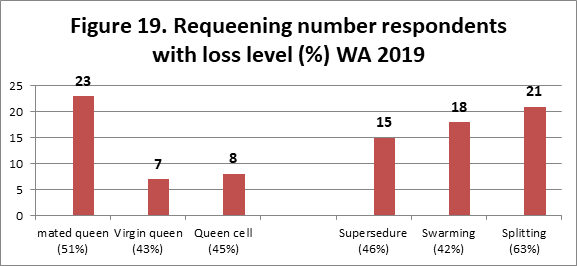

One technique to reduce mite buildup in a colony is to requeen/break the brood cycle. The question “How did bees/you requeen“ received 92 responses (more than one option could be checked). as illustrated in Figure 26. Twenty three individuals indicated they requeened with a mated queen and they had a 51% loss level, seven used a virgin queen (43% loss) and 8 used a queen cell (45% loss). A higher percentage (54 instances vs 38) said the bees requeened via Supersedure (15 instances, 46% loss), splitting (21 individuals, 63% loss) or swarming (18 individuals, 42% loss). With the exception of use of mated queen and splitting, loss levels were very similar.

Closing comments

This survey is designed to ‘ground truth’ the larger, national Bee Informed loss survey. Some similar information is additionally available on the BeeInformed website www.beeinformed.org and individuals are encouraged to examine that data base as well. Recall that the BeeInformed survey is reporting losses of the larger scale WA beekeepers not the backyarders (figure 5A.) Reports for individual bee groups with 18 or more respondents are customized and posted to the PNW website.

We intend to continue to refine this instrument each season and hope you will join in response next April. If you would like a reminder when survey is open please email us at [email protected] with “REMINDER” in the subject line. We have a blog on the pnwhoneybeesurvey.com and will respond to any questions or concerns you might have.

Thank You to all who participated. If you find any of this information of value please consider adding your voice to the survey in a subsequent season. Dewey Caron July 2019